Humans do not live by bread alone. Abundance may fill the stomach, but it doesn’t energize the soul. Somehow a life free of want and fear comes up lacking.

Adam, Eve and the Garden of Eden, the world’s first utopia, looked upon as a psychology experiment, failed. Failed in the sense that any utopia built only on abundance is already hollow. The question, then, is why? They were given food, water, sex beyond their basic needs. Their environment required no clothes. No predators threatened their existence. Labor and death were concepts not pondered. But in the end, it wasn’t enough. Why did it fail?

The answer, which will be explored further below, appears to revolve around the concept of purpose. A world; a utopia, that meets all needs but offers no purpose is not paradise but a gilded “behavioral sink.” A world without vocation, responsibility, sacrifice, striving, or narrative is a hollow reed: it stands, but it is filled with nothing. A world where nothing is required except obedience becomes unbearable stagnation. A world without purpose is not a meaningful, conscious life.

The Greeks called this deeper purpose to enliven the soul, telos. The purpose toward which life is directed. Without telos, abundance becomes a cage, a prison. With telos, even scarcity can be endured with dignity.

John Calhoun, ethologist, set out to study overpopulation but instead discovered something stranger: a behavioral sink: a kind of social and spiritual death. The colony did not collapse from too many mice, but from the breakdown of roles and meaning that eventually produced too few.

In his now famous “Universe 25” mouse utopia experiment, he showed that survival without purpose, at least for mice, collapses into withdrawal and extinction. Modern societies risk the same fate when they pursue utopia: abundance without struggle, surveillance as safety, and communal aid as the elimination of all negatives. The challenge is not simply to live, but to thrive; and thriving requires telos: a purpose.

John Calhoun’s experiment was designed to eliminate scarcity. Within a large enclosure, mice were given unlimited food and water, nesting material, and protection from predators. Eight mice were introduced, 4 male/female pairs, and the population grew rapidly, doubling every fifty-five days until it reached more than two thousand individuals (8 doublings): filling all available space. Yet despite this apparent freedom from want or fear, the colony eventually collapsed, seemingly due to extreme density and the breakdown of social roles. Fertility declined, social roles dissolved, abnormal behaviors proliferated, and reproduction ceased altogether. The colony died out, not because resources were lacking, but because abundance without freedom and meaning likely produced a breakdown. Calhoun coined the term “behavioral sink” to describe this collapse of social roles under conditions of density in a constrained space. The experiment suggested that abundance alone does not guarantee flourishing; without freedom, space, and above all, purpose, societies can unravel even in material plenty.

Subsequently psychologist Jonathan Freedman studied human responses to crowding and found that people did not exhibit the same collapse seen in Calhoun’s mice. Yet it is hard to look at modern societies and conclude that the behavioral sink: the collapse of social norms and the retreat from family formation, is entirely absent.

The Greeks would have recognized the deeper societal problem immediately. For them, the question was not simply how to survive, but how to live and prosper in accordance with telos: the end, the purpose, the fulfillment toward which life is directed. Aristotle described every being as having a natural telos: the acorn’s telos is to become an oak, the flute’s telos is to produce music, and the human telos is to live a life of virtue and flourishing, what he called eudaimonia.

Telos is purpose. For man it implies more than giving meaning to biological life. It suggests a dichotomy of mind versus consciousness: brain versus soul. Freedom from want and fear feeds the mind but provides nothing of sustenance for the soul.

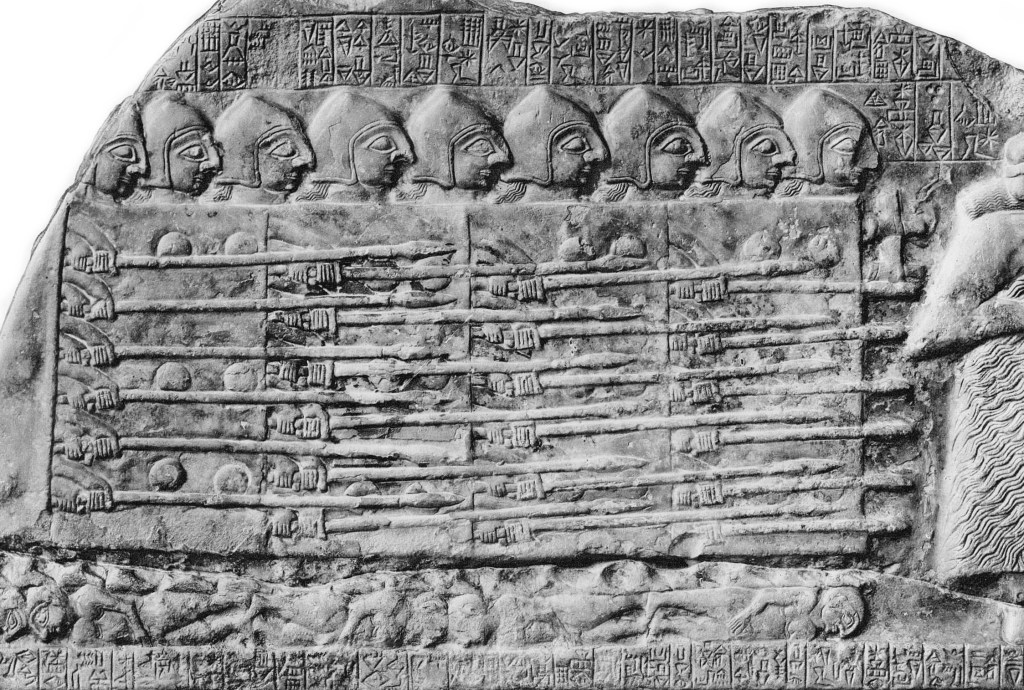

Earlier societies understood this intuitively and built cultural codes to bind abundance to purpose. Chivalry, whether in its medieval form or its later incarnation as the English gentleman’s ethic, was precisely such a telos. It required the strong to protect the weak, but also required the weak to participate in the moral order. It paired mercy with discipline, generosity with boundaries, and honor with responsibility. Chivalry was not sentiment; it was a teleological architecture that kept abundance from becoming decadence.

The mice in Calhoun’s enclosure had food, water, and shelter, but no telos. Once density eroded their social roles, a slow downward spiral ensued. Humans in modern societies face the same paradox: welfare systems, surveillance, and engineered abundance can provide material plenty, but if they strip away telos: purpose, meaning, struggle, and virtue; all outcomes drift toward dystopia.

But if the soul is only in the domain of man, why did the mice without purpose also die? Mice perceive. They have instinct and social drives. They have memory and respond to stress. But they do not have a moral imagination or the capacity to choose meaning. A mouse in the experiment could not rebel against its environment by inventing a new one. The mice died because they reached the limits of space and mind. Social instincts, stress circuits, and behavioral roles all exploded and collapsed. They died because they were in a closed world and their minds could not adapt. They were trapped.

Eden failed not because humans are like mice. Man’s mind can adapt to a life of plenty, but the soul cannot adapt to tedium. Eden failed because man was built to struggle. Perfect conditions, total comfort, safety, and abundance lead to decline, not nirvana.

Eden and Universe 25 fail for different reasons. The mice died because they could not leave. Man was expelled from Eden because he reached for a transcendence and was not permitted. Humans were not allowed to question, seek, reach, or transcend their existence. Paradise needs struggle.

So why did an omniscient God create Eden? Probably because it was never meant to be a final state but a contrast state. A teaching moment. A world without fear, scarcity, or struggle in which the human soul could discover that comfort alone is not enough. In a paradise where every need was met, the only meaningful act was the one that revealed the nature of consciousness itself: the choice to reach beyond the enclosure. The serpent did not tempt Adam and Eve with pleasure but with becoming: “you will be like gods,” awakening a longing for agency, knowledge, and purpose that abundance could not satisfy. Their disobedience was not a failure of design but the moment in which the soul recognized that a static world cannot contain a teleological being. Eden exists in the story not as a utopia that failed, but as the stage on which freedom becomes visible and the human need for telos is revealed.This pattern is not confined to myth or laboratory. When purpose collapses, societies follow the same arc as Eden and Universe 25: abundance without telos gives way to stagnation, stagnation to withdrawal, and withdrawal to demographic decline. A people who cannot articulate why life is worth living will eventually cease to create life at all. The first sign of a civilization losing its telos is not revolution or war, but falling birthrates. The quiet demographic signature of a culture that no longer believes in its own future.

Across Europe, the United Kingdom, and increasingly the United States, fertility rates have fallen well below replacement. In Germany, Italy, and Spain, fertility hovers around 1.2 to 1.3 children per woman (2.1 is replacement level). In the UK it is around 1.5; in the U.S., about 1.6. This decline is not simply biological; it is sociological. Fertility is shaped by density, cost of living, cultural norms, and moral frameworks. Where communal support is strong: rural areas, religious communities, fertility often remains closer to or above replacement. In urban centers, where density and what might be called collective individualism dominate, fertility collapses. Declining birthrates are thus a symptom of lost telos. Families are not formed because the conditions for raising children feel untenable, and because the cultural narrative of purpose has weakened.

Chivalry once provided that narrative. It linked male strength to generational duty, female dignity to communal honor, and children to the continuity of the moral order. It gave family formation a story, not merely a biological function. When chivalry collapses, fertility collapses, not because people cannot reproduce, but because they no longer know why they should.

The paradox is sharpened when abortion policies are considered. In most of Europe and the UK, abortion is legal within the first trimester, framed as healthcare and autonomy. In the U.S., abortion remains contested but widely available in many states. Here lies the disconnect: abortion is framed as expanding individual autonomy: the freedom from unwanted obligation, while fertility decline reflects the collapse of collective freedom, the freedom to flourish and raise children. Societies expand freedom at the individual level while eroding it at the collective level. Autonomy is preserved, but telos is undermined.

To buttress declining populations, European countries and the UK have encouraged immigration. Migrants often come from regions with higher fertility rates, offsetting demographic decline and supporting aging workforces. Immigration is thus a pragmatic solution to population collapse: but it does not address the root causes: density, freedom, and telos. It is a patchwork repair, adding new blocks to a crumbling wall without restoring the foundation. The deeper paradox remains: abundance without purpose produces collapse, and immigration cannot substitute for the conditions that allow families to thrive, especially if society’s new members are supported without shared cost, shared culture, or shared telos.

Density alone does not dictate outcomes; it interacts with telos, governance, and cultural frames. Lagos, Nigeria, is one of the most densely populated and chaotic cities in the world, often described as bordering on ungovernable. Infrastructure is weak, governance is fragmented, and daily life is improvisational. Yet fertility remains high. The reason is that telos: family, lineage, and communal identity, remains intact. In Lagos, children are wealth, kinship and clan networks are survival, and religion provides meaning. Even in smothering density, purpose sustains resilience. The city may be chaotic, but it is alive.

By contrast, the homeless encampments of Los Angeles resemble Lagos in their improvisational density and lack of formal governance. Tents, makeshift shelters, and informal economies proliferate. Yet here fertility does not thrive. Rampant mental illness and drug use erode telos. The cornerstone of family, community, and purpose has collapsed. What remains is density without meaning, abundance without direction. Food programs, shelters, and aid exist, but they do not restore purpose. The result is stagnation and despair rather than resilience. Los Angeles encampments show that chaos without telos collapses into dysfunction.

Bangkok, Thailand, illustrates the opposite extreme. Governance is strong, infrastructure is orderly, and surveillance is extensive. Yet fertility has collapsed to ultra-low levels. Here, telos has been eroded not by chaos but by over-governance and modernization. Families shrink, marriage is delayed, and children are no longer seen as wealth or purpose. Bangkok epitomizes the behavioral sink in human form: density magnified by order but hollowed of telos.

These contrasts reveal the missing quadrant: a society that pairs order with telos. This was the promise of chivalry. Lagos has telos without order; Bangkok has order without telos; Los Angeles has neither. Chivalry represents the fourth possibility: order with purpose, structure with meaning, boundaries with dignity.

Together these cases sharpen the living paradox. Lagos thrives in chaos because telos survives. Los Angeles collapses in chaos because telos has dissolved. Bangkok collapses in order because telos has been eroded by governance. The lesson is clear: density is the stressor, but telos is the barrier to collapse. Where telos is strong, fertility can endure even in smothering conditions. Where telos is weak, density accelerates collapse. A utopia pursued through governance can become more dystopian than chaos if it erodes purpose. Man needs a purpose. Without it, abundance becomes nothing more than a cage: a prison with flowered curtains; with it, even hardship can be transformed into amber waves of plenty.

Urban America provides its own cautionary tale. Under Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, HUD launched massive urban renewal programs meant to eliminate “slums.” Entire neighborhoods once vibrant with shops, churches, and homes were razed. In their place rose brutalist public housing towers like Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis and Cabrini-Green in Chicago. Instead of dispersing poverty, these projects concentrated it vertically, creating ghettos in the sky. The architectural order stripped away human scale, while the destruction of community fabric erased telos. Where once there were family networks, small businesses, and congregations, there was now isolation, surveillance, and stigma. The result was alienation, crime, and eventual demolition. HUD’s well‑intentioned utopia became a dystopia, echoing Calhoun’s mice: abundance of shelter without freedom or telos collapses into dysfunction.

Chivalry offers a counterpoint here as well. It was a social contract, not a bureaucratic one. It preserved dignity by pairing generosity with expectation, aid with responsibility, and protection with participation. Modern welfare systems sever the relationship and keep only the transfer. The result is dependency instead of resilience, abundance without telos.

Surveillance adds another layer to the modern enclosure. In Calhoun’s experiment, the enclosure walls were the hidden constraint. For humans, surveillance plays a similar role. In China, the social credit system tracks citizens through cameras, financial records, and online behavior, with scores affecting access to jobs, travel, and services. In Europe and the U.S., facial recognition, biometric ID, and behavioral profiling are increasingly common. Awareness of being watched erodes anonymity, adds stress, and modifies behavior. Surveillance is the human equivalent of the enclosure walls. It defines the boundaries of freedom, even in abundance.

The paradox is that surveillance is justified as safety, efficiency, or order, yet in practice it adds to the stress of density, accelerating the very breakdown it claims to manage. It is the human version of the behavioral sink: not scarcity, but suffocating constraint. And more deeply, surveillance erodes telos by reducing individuals to data points, stripping away the individual dignity of purpose.

Chivalry again stands as the opposite principle: internal discipline instead of external enforcement. A chivalric society requires fewer walls, fewer cameras, fewer bureaucratic constraints, because the code itself governs behavior. Surveillance grows where virtue shrinks.

The pursuit of utopia often plants the seeds of dystopia. Calhoun’s mice dramatize this paradox, and human societies repeat it in subtler ways. Utopia promises abundance and safety, but struggle, risk, and constraint are what give life meaning and resilience. Remove them, and individuals may feel aimless. The enclosure gave plenty, but the will to live wilted. The mice could not leave, explore, or repurpose their world.

For humans, welfare states or surveillance societies may provide abundance but limit autonomy. The invisible walls matter more than the food. Collective solutions often replace organic bonds with bureaucratic systems. Parenting, community, and moral frameworks weaken when the state or collective “fixes” everything. Individuals withdraw because the frame of telos collapses. Even in abundance, awareness of being watched adds psychological weight. For mice, the enclosure was the hidden constraint. For humans, cameras and social scoring systems are the modern equivalent.

The collective aims at population-level stability, but the individual seeks personal meaning, agency, and dignity. When collective solutions optimize for averages, individuals at the margins feel alienated. The bell curve of individuality is reduced to a spike. The revolt or collapse is not irrational; it is a signal that something is not working as intended. It shows that utopia defined by the collective may not align with the individual’s need for telos. The collective optimizes for stability, the individual thrives on agency, risk, and purpose. When those needs evaporate, revolt or withdrawal emerges.

Examples abound in modern policy. Guaranteed income experiments often show that recipients reduce work hours modestly. The reduction is not usually total withdrawal; it is often fewer hours, more time for caregiving, education, or leisure. But the symbolic effect matters: when income is guaranteed, the incentive to work as necessity weakens. The “beautiful ones” of Calhoun’s mice resonate here: abundance without struggle risks withdrawal.

Food stamps provide nutrition support to low-income households, but fraud and misuse exist, and some recipients may not be in dire need but qualify through loopholes or marginal thresholds. The program can attract dependency, with households remaining on benefits long-term rather than transitioning out. Help for the needy becomes normalized as entitlement, and the boundary between “in need” and “not in need” blurs, creating resentment and undermining trust in communal solutions.

The paradox is structural: help for the individual expands freedom‑from immediate crisis, but attracts broader participation, dilutes targeting, and sometimes erodes freedom‑to flourish. Programs designed as umbrellas risk becoming enclosed boxes; constraints that reshape behavior in unintended ways. And most importantly, they risk eroding telos by reducing life to consumption and dependency rather than purpose and flourishing.

Chivalry resolves this paradox by insisting that mercy must be paired with measure. The English gentleman was gallant toward women and the lower classes, but “hard as nails” when duty required it. This duality; compassion with boundaries, is precisely what modern systems lack. They know how to help, but not how to say no. Chivalry understood that saying no is sometimes the highest form of care, because it preserves dignity and agency. All good parents know this instinctively.

The lesson is not that communal aid is bad, but that design matters. If aid is too broad, it attracts those beyond need. If aid is too narrow, it misses the vulnerable. If aid removes all struggle, it risks eroding resilience. If aid balances support with responsibility, it can rebuild freedom‑to‑flourish. The paradox is that governments often attempt to engineer away all negatives, but the outcomes drift toward fragility rather than resilience. The mice in Universe 25 were given abundance: no hunger, no predators, no scarcity. Yet the absence of struggle did not produce flourishing; it produced an unremitting, total collapse.

Humans in modern welfare states face a similar paradox. Governments try to eliminate negatives: poverty, hunger, homelessness, drug use, through programs and interventions. Yet the outcomes are mixed: dependency, loss of initiative, bureaucratic surveillance, and sometimes deeper alienation. Erase all struggle, and resilience erodes. Limited means is not the enemy; it is the forge of adaptive capacity. Without struggle and purpose, societies grow brittle and collapse. Challenges often provide purpose. When all negatives are removed, individuals may feel rudderless and adrift.

To eliminate negatives, governments also expand monitoring: drug tests, social scores, biometric IDs. This adds stress, reproducing the under‑the‑microscope effect. Policies aimed at fixing one problem can create others. Housing programs may provide shelter, yet leave mental health and community breakdown untouched, creating dependency instead of resilience. Surveillance systems are justified as safety but erode privacy and increase stress in dense populations. The balance is razor‑thin. Too much intervention suffocates autonomy; too little starves collective flourishing. The missing element is telos. Without purpose, abundance becomes dystopia.

The pursuit of utopia, removing all negatives, often produces dystopian outcomes because it confuses abundance with flourishing. Flourishing requires freedom, struggle, and telos. Utopia removes struggle, but in doing so, removes meaning. The result is collapse: the behavioral sink in mice, fertility decline and alienation in humans. The challenge is to design programs that support resilience and meaning, rather than erasing all negatives.

A moral cycle often attributed to G. Michael Hopf: “Hard times create strong men. Strong men create good times. Good times create weak men. Weak men create hard times,” encapsulates the utopia-to-dystopia paradox. Hopf’s cycle is not merely historical; it is teleological. Societies rise or fall according to the strength of their purpose.

Population decline is not linear, nor is it destiny. It is cyclical, shaped by density, freedom, and telos. When societies become too dense, when surveillance erodes autonomy, when communal bureaucracy substitutes for organic bonds, fertility and flourishing decline. Yet when density eases, when freedom is restored, when telos is rediscovered, populations rebound. History shows this rhythm: humanity has survived bottlenecks, plagues, wars, and famines, and each time rebounded when purpose was renewed.

The Greeks understood that man needs a telos, an end toward which life is directed. Without telos, abundance becomes a monkey cage; with telos, even scarcity can be endured with dignity. Calhoun’s mice remind us that survival is not about food and shelter alone. It is about freedom, meaning, and purpose.

Modern societies risk repeating the experiment when they pursue utopia as abundance or the absence of need without struggle, surveillance as safety, and communal aid as the elimination of all negatives. The paradox is that such utopian attempts often promote dystopian outcomes. The challenge is not to remove every negative, but to build an airy house on a foundation of resilience, dignity, and telos. Only then can abundance become flourishing, and only then can societies escape the behavioral sink.

Chivalry offers a final lesson: flourishing requires mercy, measure, and mettle. Mercy to lift the vulnerable. Measure to set boundaries that preserve dignity. Mettle to uphold the moral order even when it is difficult. Chivalry is not medieval nostalgia; it is a teleological architecture that binds abundance to virtue. Without such a code, abundance becomes a cage. With it, even hardship becomes a forge.

Chivalry once served as the mediating code between secular authority and sacred telos, binding worldly power to transcendent purpose. It stood in the space where kings governed and churches taught, ensuring that strength was disciplined by virtue and that mercy was bounded by responsibility. But in the modern age, this mediating role has eroded. Secular governments have expanded into moral territory, while many churches, entangled in state funding, NGO partnerships, and bureaucratic incentives, have softened their prophetic edge, echoing the language of administration rather than the guidance of the soul. When the sacred becomes an extension of the state, it can no longer offer counter‑telos; it becomes a chaplaincy to the administrative order. Money talks, and institutions drift toward the priorities of their patrons. The result is a vacuum where chivalry once stood: no moral architecture to restrain abundance, no internal compass to replace external surveillance, no code to bind freedom to responsibility.

Striving toward a vision of utopia is a failure to see that purpose, not perfection, sustains a society.

(Post‑script: Calhoun’s mice peaked at roughly 15–18 months and collapsed by about 48 months: an approximate 1/3 to 2/3 split between peak population and extinction. Universe 25 was the 25th iteration of his utopia experiments; earlier versions ended prematurely, but the behavioral patterns he observed: social breakdown under abundance and density, were consistent across his work. Scaled to humans: U.S. population is projected to crest around 2040–2080, suggesting the attempt at utopia began around Johnson’s Great Society, followed by a ~200‑year decline toward collapse (2240–2280). Strikingly, this peak falls within Isaac Newton’s own apocalyptic horizon, which he argued could not arrive before 2060. Abundance, demography, and prophecy all converge to remind us that abundance without telos has a half‑life, or at least a shelf‑life. Strangely, that also suggests that the timing of the apocalypse is of our own making: as a society the time to die is our choice.)