“What I am going to say is not a dogma of faith but my own personal view: I like to think of hell as empty; I hope it is.” Pope Francis, 14 January 2024.

Few utterances from the papal class have landed with more confusion than Pope Francis’s remark. It is muddled, misleading, and ultimately misconstrued, though with two thousand years of ecclesiastical history, one might find other contenders. To be fair, only two papal statements have ever been deemed infallible: Pius IX’s definition of the Immaculate Conception and Pius XII’s proclamation of the Assumption of Mary. Nearly everything else falls under the category of secular opinion. So secular opinion will have to stand along with my slightly pedantic philosophical flourish on the topic.

The trouble with Francis’s remark is not that it expresses hope in an infinitely merciful God. It does, and God is. Humans are extravagantly hopeful when it comes to their own stake in the hereafter. But the Pope’s phrasing seems to remove the ultimate incentive to live a moral life. If there is no hell, then there are no boundaries to one’s actions. On its surface, the statement reduces moral teaching and punishment for sin to negligible outcomes. Two millennia of urging humans to keep their souls pure dissipate in an instant. It treats hell as if it were a place one might stroll into and find as empty as a modern mall, then decide to shop elsewhere; Amazon, perhaps. It blurs the line between our desire to avoid suffering and the eschatological reality in which immorality and punishment are tied to free will. Judgment remains inevitable, for better or worse, and forever. The qualifier “I hope it is” reduces judgment to a wish for mercy rather than a real consequence of one’s actions. It also suggests that the Pope is worried not only about your soul but his own. A merciful God will save a repentant sinner, but hoping is an insecure measure of remorse.

In short, Francis managed an exceptionally muddled rendering of the Augustinian and Thomistic view that hell is the final state of a person who refuses the good and closes themselves off to God’s love. To be fair, clarity is difficult when the very word “hell” carries millennia of conflicting meanings, teachings, and eschatological traditions.

This confusion is inevitable because the Christian vocabulary of the afterlife is a translucent overlay of older worlds, cultures, and languages. The Hebrew Scriptures speak of Sheol, a shadowy realm of the dead with no inherent moral judgment, not a prison for the wicked, but simply the condition of being dead. In Christian theology, “[Jesus] was crucified, died, and was buried. He descended into hell.” The “hell” in this line refers to Sheol (often rendered as Hades), the realm of the dead into which Christ entered. His descent breaks open the barrier between death and divine life. In Sheol, He liberates the righteous dead and inaugurates the post‑biblical landscape of heaven, purgatory, and the final hell of separation from God’s love. After this event, Sheol becomes vestigial in Christian thought, a name without a continuing function. Christianity judges the soul immediately and resurrects the body later, whereas Judaism gives the soul varied post‑death experiences but reserves final judgment for bodily resurrection.

In the ancient Greek world, Hades begins much like Sheol: a neutral underworld where all the dead reside. Only the exceptional are diverted: heroes to the Elysian Fields, mythic offenders to Tartarus. Plato’s Myth of Er overlays this older realm with Socratic soulfully infused moral vision: judgment, reward, punishment, and reincarnation. Over time, mythic Hades and Platonic moral Hades blend into a single, more complex vision. Early Judaism and early Greek religion both had neutral underworlds, but the Greeks moralized theirs first. Socrates’ preoccupation with the soul made him less a secular philosopher than a theological pioneer or prophet if you will.

Hell does not take on its later punitive shape until the New Testament’s use of Gehenna, a metaphor drawn from a real valley outside Jerusalem associated with corruption and divine judgment. In the Gospels, Gehenna is a warning, not a mapped realm. Jesus uses it as prophetic shorthand for the consequence of a life turned away from the good. A moral and relational judgment rather than the later imagery of fire, demons, or descending circles. Gehenna is not the fully developed hell of medieval imagination but a symbol of what becomes of a life that refuses the shape of love.

Augustine, in the 4th century, further develops hell as a condition rather than a location. Hell is self‑exclusion: the soul turns away from God and locks itself into disordered love. Suffering arises from the consequences of one’s own choice; separation from the source of all goodness. This state is eternal not because God withholds mercy but because the will can become fixed in refusal. Fire is both real and symbolic: suffering is real, though its mode lies beyond language and expression.

Aquinas in the 13th century builds on Augustine by grounding hell in Aristotelian metaphysics. Hell is the definitive state of a rational soul that dies in mortal sin. The soul’s refusal of God is not only moral failure but a failure of rational nature. Aquinas distinguishes poena damni (the pain of loss) and poena sensus (the pain of sense). At death, the soul’s direction becomes fixed; eternal destiny is determined not by divine wrath but by the soul’s own settled choice. At the resurrection, the body joins the soul in its suffering. William Blake captures this Thomistic vision in his illustration of Dante conversing with the heretic Farinata degli Uberti in the fiery tombs of the sixth circle.

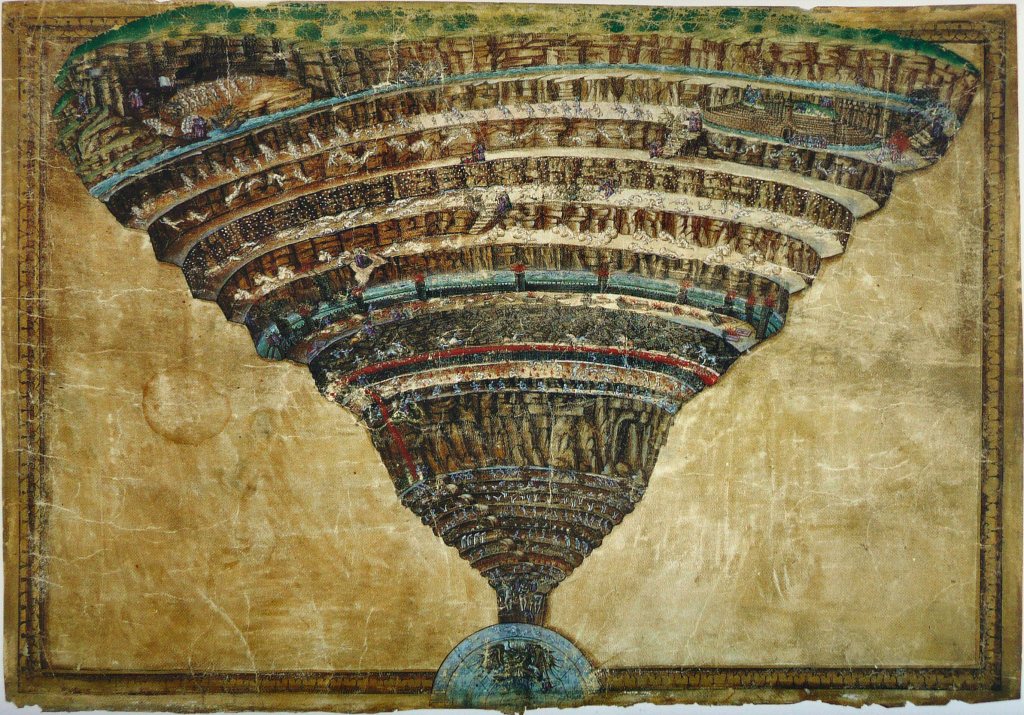

Aquinas provided his near‑contemporary Dante with the moral architecture that allowed hell to shift from concept to vividly imagined landscape. In the Inferno, Dante transforms that architecture into a descending spiral of circles, each calibrated to a deeper distortion of the good and a harsher form of alienation. At the frozen center lies the absolute loss of God’s presence and love. Dante’s genius is giving spatial form to moral trajectory. Sin becomes architecture.

Modern Christians often imagine hell through Dante’s nine circles without realizing it. Levels, tailored punishments, structured descent, these are Dante’s inventions, not biblical categories. Yet his poetic vision has become the default mental picture of what it means to lose God’s love. His circles are not doctrine, but they express a truth the tradition affirms: the more a soul rejects the good, the more it collapses inward, freezing into itself; a thermodynamic loss not of heat but of God’s presence. Dante’s afterlife remains a symbolic map of the soul’s self‑chosen distance from God, shaping imagination long after its theology has been forgotten or more likely, ignored.

By the modern era, hell has traveled a long road: from Sheol and Hades, through Gehenna, into Augustine’s self‑chosen alienation, Aquinas’s metaphysical finality, and Dante’s architectural imagination. Each stage sharpens the moral stakes, but none claims to know the final census of the saved and the lost.

It is here that Hans Urs von Balthasar, the 20th‑century Swiss theologian, offers a different starting point: beauty as the mode of God’s self‑revelation. God becomes visible through form, radiance, and splendor; beauty is the shape of truth and goodness. For Balthasar, salvation is participation in God’s dramatic love: the drama in which God and humanity meet in freedom. Christ is the central actor whose obedience, self‑gift, and descent into the depths of human abandonment open the way for every person to enter divine life. Salvation is aesthetic: God is Beauty, Christ is Beauty made visible, and salvation is the soul learning again to see the Beauty that is God.

Balthasar insists that Christ’s descent into Sheol means no place remains where God is not. Hell remains a real possibility, but God’s love hopes for every person, even as human freedom is never overridden. Salvation is the soul being drawn freely, dramatically, and beautifully into the radiant self‑giving love of the Triune God.

Balthasar offers a final, chastened note: Christians may hope that all will be saved, but they may never presume it. Hope is a virtue; presumption a trespass. Hell remains real, possible, and bound to freedom, yet the Christian stance toward final judgment is not certainty but reverent uncertainty. We may hope that no soul ultimately refuses the good, but we may not claim to know the mind of God. This hope is not optimism; it is the trembling aspiration of the penitent, something beyond the insecure measure of remorse that opened this essay.

In the end, tradition leaves us with a paradox: hell is the consequence of free-will, yet hope is the proper response to divine mercy. Between those two poles, freedom and mercy, the human soul stands. And perhaps that is the only place it can stand: not in presumption, not in despair, but in the narrow space where hope remains possible without ever becoming a certainty. Perhaps this is what Pope Francis, in his inelegant phrasing, was reaching for.

By the time afterlife dogma and secular imagination knock on our modern door, “hell” is less a settled place or concept than a linguistic suitcase and atlas stuffed with conflicting contents and branching paths toward judgment. Hope without presumption is allowed; hiding never is.

Graphic: Chart of Hell by Sandro Botticelli, c1480. Vatican City. Public Domain.