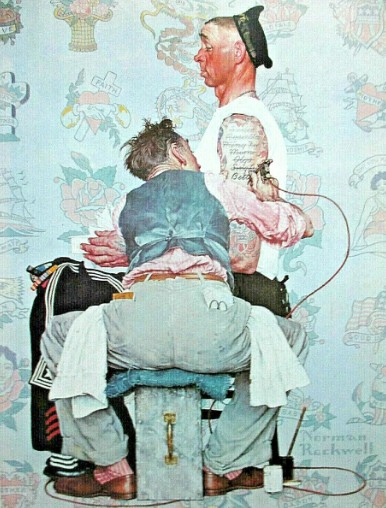

Norman Rockwell, a name synonymous with American Realism, was a master of meticulous detail, yet he never failed to brush a thread of whimsy and rustic existence onto the canvases of his iconic paintings.

Norman Rockwell, an iconic painter of American life, was born on 3 February 1894 into a comfortable New York City family. His father, a lover of Charles Dickens, often sketched illustrations from books, planting early seeds of creativity in young Norman. His mother, overprotective yet proud of her English heritage, spoke often of her artistic but unsuccessful father, whose unrealized dreams seemed to echo in the household. Art wasn’t just a pastime for Rockwell; it pulsed through him, and by age 12, he had resolved to draw for a living, though painting would come later in his journey as an artist.

As a teenager, Rockwell pursued artistic training at the National Academy of Design and later at the Art Students League, where he studied under the influence of Howard Pyle, the renowned illustrator of boys’ adventure tales. Pyle, who had founded the school’s philosophy through his own teachings and legacy, left an indelible mark on Rockwell, shaping his lifelong passion for weaving narrative into art. Before he turned 16, Rockwell landed his first commission—four Christmas cards—a modest start for a boy already dreaming big. By 18, he was painting professionally full-time, his talent unfolding with the quiet determination of youth finding its purpose.

In 1916, Rockwell began his legendary run with The Saturday Evening Post, creating covers that would grace the magazine for the next 47 years. Over that span, 322 of his paintings became what the Post proudly dubbed “the greatest show window in America.” Through these works, Rockwell offered a mirror to the nation—sometimes nostalgic, often tender, always human—reflecting everyday moments that resonated deeply with millions.

While his career soared with the Post, city life never suited him. In 1939, he traded New York’s clamor for the rolling hills of Vermont, and later, in 1953, settled in Massachusetts. These rural landscapes became his muse, dominating his canvases for the first three decades of his career. Rockwell was no haphazard artist; he was methodical, even obsessive, following a rigorous six-step process to bring his visions to life: brainstorming ideas, sketching rough outlines, photographing staged scenes with real people, crafting detailed drawings, experimenting with color studies, and only then committing paint to canvas. Each step was a labor of love, a tip of the hat to the America he loved.

At the heart of his art was a simple, profound drive. As Rockwell himself put it, “Without thinking too much about it in specific terms, I was showing the America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed.” His paintings weren’t just pictures, they were invitations to see the beauty in the ordinary, the dignity in the overlooked; we see not just an artist, but a storyteller who believed in the quiet goodness of people, brushstroke by brushstroke.

Source: The Norman Rockwell Treasury by Thomas S. Buechner, 1979. Norman Rockwell Museum. Graphic: The Tattooist by Norman Rockwell, 1944, The Brooklyn Museum.