Mikhail Bulgakov’s White Guard, set during the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917–1921) amid the Russian Civil War, captures Kyiv in an existential power struggle against varied forces: Ukrainian nationalists allied with German troops, the White Guard clinging to Tsarist dreams, Lenin’s Bolsheviks closing in, plus Poles and Romanians. Against this bloody backdrop, Bulgakov crafts a semi-autobiographical tale of loss and fatalism, culminating in a nihilistic realization of humanity’s purpose: “But this isn’t frightening. All this will pass. The sufferings, agonies, blood, hunger, and wholesale death. The sword will go away, but these stars will remain… So why are we reluctant to turn our gaze to them? Why?”

Bulgakov, a doctor of venereal diseases like the book’s protagonist Alexei Turbin, knew hopelessness. In 1918, syphilis was a scourge, often incurable, leading to madness, mirroring the war’s societal decay. Alexei volunteers for the White Guard, tending to horrors he can’t heal, his efforts dissolving in a dream: “shadows galloped past…Turbin was dying in his sleep.” War becomes a disease, resistance futile. Yet Bulgakov’s lens widens. Sergeant Zhilin dreams of Revelation, “And God shall wipe away all tears…and there shall be no more death,” finding humility in cosmic indifference. Petka, an innocent, dreams simply of a sunlit ball, untouched by great powers. “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God” (Matthew 5:8).

Then, out of dreamland into the light: “All this will pass.” The stars endure, wars fade. Writing in the 1920s after the White defeat, Bulgakov channels Russian fatalism—Dostoevsky’s inescapable will, Chekhov’s quiet surrender. But he’s not fully broken. His “Why?” pleads, mocks, resists. Why not look up? Survival is luck, death equalizes, yet fighting a losing battle confronts our nothingness. Kyiv falls, the Bolsheviks threaten, the White Guard vanishes, still, Bulgakov continues to ask. Why?

He blends despair with irony, a doctor mocking death as the stars watch. The German expulsion of the Reds in 1918 briefly eased bloodshed, but 1919 brought worse, “Great was the year and terrible the Year of Our Lord 1918, but more terrible still was 1919.” History moves on; stars don’t care. Bulgakov’s question lingers: Why? To fight is to live, fate be damned.

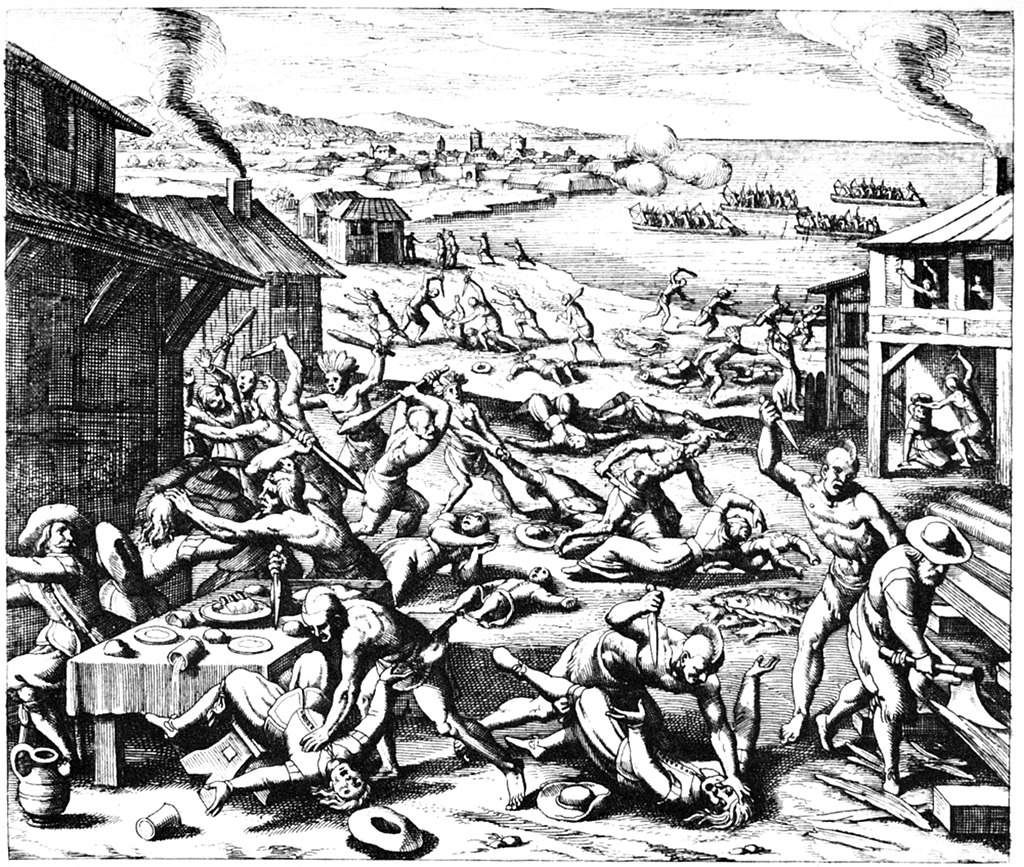

Source: White Guard, Mikhail Bulgakov, trans. Marian Schwartz. Graphic: Ukrainian Soldiers circa 1918.