Sir Robert Filmer, a mostly forgotten 17th century political theorist, claimed that kings ruled absolutely by divine right, a power he believed was first bestowed upon Adam.

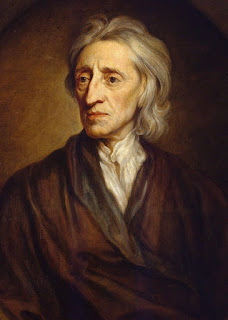

In his First Treatise of Government, John Locke thoroughly shredded and debunked this theory of divine rights of monarchs to do as they pleased. Locke with extensive use of scripture and deductive reasoning demonstrated that ‘jus divinum’ or the divine right to rule led only to tyranny: one master and slavery for the rest, effectively undermining the natural rights of individuals and a just society.

Filmer, active during the late 16th to mid-17th century, argued that the government should resemble a family where the king acts as the divinely appointed patriarch. He erroneously based his theory on the Old Testament and God’s instructions to Adam and Noah. He used patriarchal authority as a metaphor to justify absolute monarchy, arguing that kings can govern without human interference or control. Filmer also despised democracies, viewing monarchies, as did Hobbes, as the only legitimate form of government. He saw democracies as incompatible with God’s will and the natural order.

Locke easily, although in a meticulous, verbose style, attacked and defeated Filmer’s thesis from multiple fronts. Locke starts by accepting a father’s authority over his children, but, in his view, this authority is also shared with the mother, and it certainly does not extend to grandchildren or kings. Locke also refutes Filmer’s assertion that God gave Adam absolute power not only over land and beast but also man. Locke states that God did not give Adam authority over man for if he had, it would mean that all below the king were ultimately slaves. Filmer further states that there should be one king, the rightful heir to Adam. Locke argues that there is no way to resolve who that heir is or how that could be determined. Locke finishes his argument by asserting that since the heir to Adam will be forever hidden, political authority should be based on consent and respect for natural rights, rather than divine inheritance: a logical precursor to his Second Treatise of Government, where Locke profoundly shaped modern political thought by advocating for consent-based governance.

Source: First Treatise of Government by John Locke, 1689. Graphic: John Locke by Godfrey Kneller 1697. Public Domain.