Time, life, and physics are inseparably intertwined. Remove time from our lives or our equations and we are left with a null set; a void where very little makes sense, and nothing moves forward or backwards. Birthdays, compound interest, and prison sentences lose their definitions. Einstein’s spacetime, relativity, and the absolute speed of particles all collapse if time is reduced to mere concept rather than a dimension woven into the fabric of the universe.

Time is real, yet not what we think. It is measurable, yet subjective. Physical, yet metaphysical. Created, yet transcended. It is time, and not time.

To confront this metaphysical and ontological puzzle, we must go back and consider how others have wrestled with it. In Book XI of Confessions, Augustine famously writes: “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain it to one who asks, I do not know.” He knew time intimately yet could not articulate it; a paradox of intuitive knowledge that resists definition.

For Augustine, time is the tension of the soul: distentio animi, stretched between memory, perception, and anticipation. I would go further: time is the unease of the soul, the awareness that our life is not merely sequential but weighted. Each present moment becomes a record, a catalogue of change, where memory and expectation converge upon the ubiquitous now.

From this knotty discomfort, Augustine turns to consciousness. We do not measure existence as an external construct, nor as Einstein’s spacetime, but hold past, present, and future together in awareness. This is the soul’s way of ordering experience: a catalogue of change. An AI approaches memory similarly; not as a flowing timeline but as indexed facts retrievable when relevant. What for humans is the soul’s ledger of experience, for AI is a ledger of durable notes. And yet both remain finite catalogues.

Augustine presses further: God transcends even this. For us, awareness gathers past as memory and future as expectation, but God simply is: beyond sequence, beyond catalogue, beyond event. Time itself began with creation; sequence and change belong only to the created. God exists outside of it, the eternal source from which all temporal becoming flows.

Thomas Aquinas also saw time not as a substance but as a measure: the numbering of motion by before and after. Time, for him, comes into being with creation and is experienced only by mutable beings, for without change there is no succession, and without succession there is no time. Humanity lives within this flow: we need time to give shape to purpose, meaning, and becoming. But God is utterly immutable, without before or after. He does not move from past to future but exists in a timeless presence; eternity as the simultaneously whole possession of life. All times are present to Him at once, not as a sequence but as a single, perfect act of being.

Pope Benedict XVI, following Augustine and Aquinas, insisted that eternity is not endless time but timeless presence. To bind God within sequential time would reduce Him to a creature among creatures. God does not foresee as a prophet would; He simply is, in relation to all times.

This ‘eternal now,’ or what Boethius calls the ‘eternal present,’ expresses his argument that eternity is not infinite duration but the perfect simultaneity of divine presence. God’s knowledge is not ours extended indefinitely; it is categorically different. Thus, free will and an all‑knowing God are not contradictions. According to Boethius, “whatever lives in time lives only in the present,” whereas God lives in the eternal present: totum simul, the all‑at‑once‑ness of divine life.

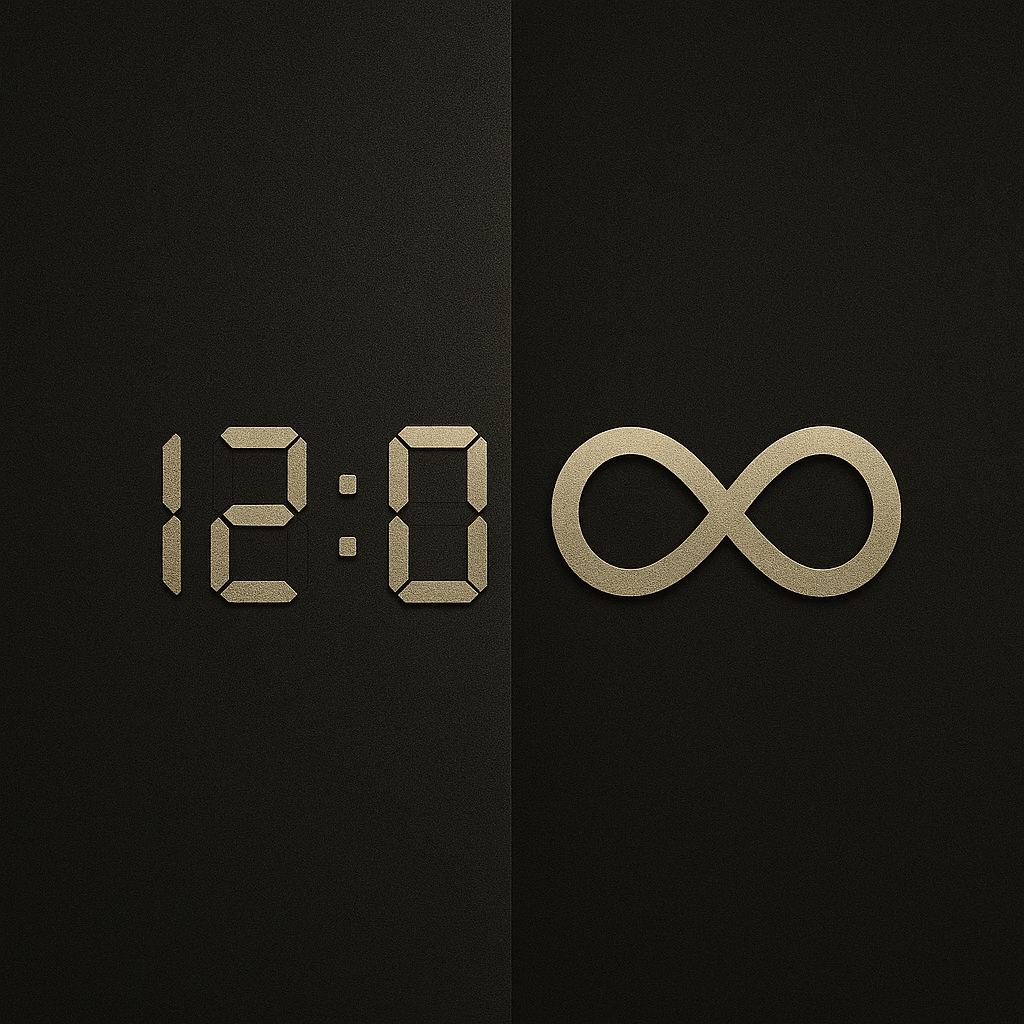

Where Christian thought places God beyond time, the Greeks placed humanity within two modes of time: Chronos and Kairos. Chronos is quantitative time; measured, sequential, countable. It gives life structure, the frame by which we track change. Kairos is qualitative time; the opportune moment, the ripeness of action, the fullness of meaning. Chronos watches the clock; Kairos watches life. Chronos measures duration; Kairos measures significance.

Together they reveal that time is not merely a dimension we move through but a dual register of existence: one that counts our days and one that gives those days weight.

Time, from ancient philosophers and theologians to modern physicists, has evolved. Theology gives us a God of timeless presence. Newtonian time was absolute, measurable, and continuous. Einsteinian time became relative, elastic, and inseparable from space. Quantum time is probabilistic, discontinuous, sometimes irrelevant. Entanglement seems to ignore time altogether. The arc bends from time to not‑time. From time to timelessness.

If theology gives us the metaphysics of time, physics gives us its language; how time behaves, how it binds itself to matter, motion, and measurement.

The physical story begins with Newton, who imagined time as absolute: a universal river flowing uniformly for all observers. In Newton’s cosmos, time is the silent metronome of the universe, ticking identically everywhere, indifferent to motion or perspective. It is Chronos rendered into mathematics.

But Einstein suppressed that certainty. In special relativity, time is no longer absolute but elastic. It stretches and contracts depending on velocity. Two observers moving differently do not share the same “now.” Time becomes inseparable from space, fused into a four‑dimensional fabric: spacetime. Where motion through one dimension alters experience of the others. The universe no longer runs on a single clock; it runs on countless local clocks; each tied to its own frame of reference.

General relativity deepens the strangeness. Gravity is not a force but the curvature of spacetime itself. Massive objects bend the temporal dimension, slowing time in their vicinity. A clock on a mountaintop ticks faster than a clock at sea level. Time is not merely experienced; it is shaped by mass and speed. It bends under pressure. It is not the absolute we imagine.

If Newton’s time was a river, Einstein’s time is a landscape; warped, uneven, inseparable from the terrain of existence.

Yet even Einstein’s vision wanes at the smallest scales. Quantum mechanics introduces a world where time behaves less like a smooth dimension and more like a probabilistic backdrop. Particles do not trace continuous, classical arcs but inhabit shifting probability fields. Events unfold not deterministically but as clouds of possibility collapsing into actuality when observed.

And then comes entanglement; the phenomenon Einstein called “spooky action at a distance.” Two particles, once linked, remain correlated no matter how far apart they travel. Their states are not merely synchronized; they are one system across space. Measurement of one instantaneously determines the other, as if the universe refuses to let them be separated by distance or by time.

Entanglement suggests that relation is woven deeper than sequence. The universe reveals patterns of connections that seem to operate under different temporal conditions altogether.

And this loosening of temporal order is not confined to the quantum scale; it appears again, in a different register, at the largest scales of the cosmos.

The universe’s expansion gives the appearance of faster‑than‑light recession, not because objects outrun light, but because spacetime itself stretches. And in the vast reaches where dark energy dominates, the very markers of time grow thin. Beyond the realm shaped by matter, time begins to lose its meaning; dark energy becomes a kind of luminous emptiness, a region where temporality itself seems to fade.

But the universe does not remain at its extremes; the very small and the very large fold back into the ordinary world we inhabit.

And yet, when these quantum strangenesses are averaged over countless particles, when probabilities smooth into certainties and fluctuations cancel out, the world resolves once more into Newton’s calm, reassuring, continuous order. The granular becomes smooth. The uncertain becomes predictable. The timeless hints collapse back into the familiar rhythm of clocks and orbits. Newton’s universe reappears not as the foundation of physics, but as its limit; the shape reality takes when the deeper layers approach infinity.

And it is precisely at this limit that physics brushes against theology. For if entangled particles share a state beyond temporal separation, then timelessness is not merely a divine abstraction but a feature of the universe’s foundational structure. Augustine’s claim that God exists outside time finds an unexpected shadow in quantum theory: the most fundamental connections in reality are not mediated by time at all.

Where theology speaks of God’s eternal now, quantum mechanics reveals systems that behave as if they participate in a kind of physical “now” that transcends sequence. Where theology insists that God is not bound by before and after, entanglement shows us correlations that ignore the very notion of before and after.

Physics does not prove theology. But it points toward a universe where timelessness is not only conceivable but woven into the fabric of existence: an image of everything at once: totum simul, a vision that dissolves the moment we try to picture it.