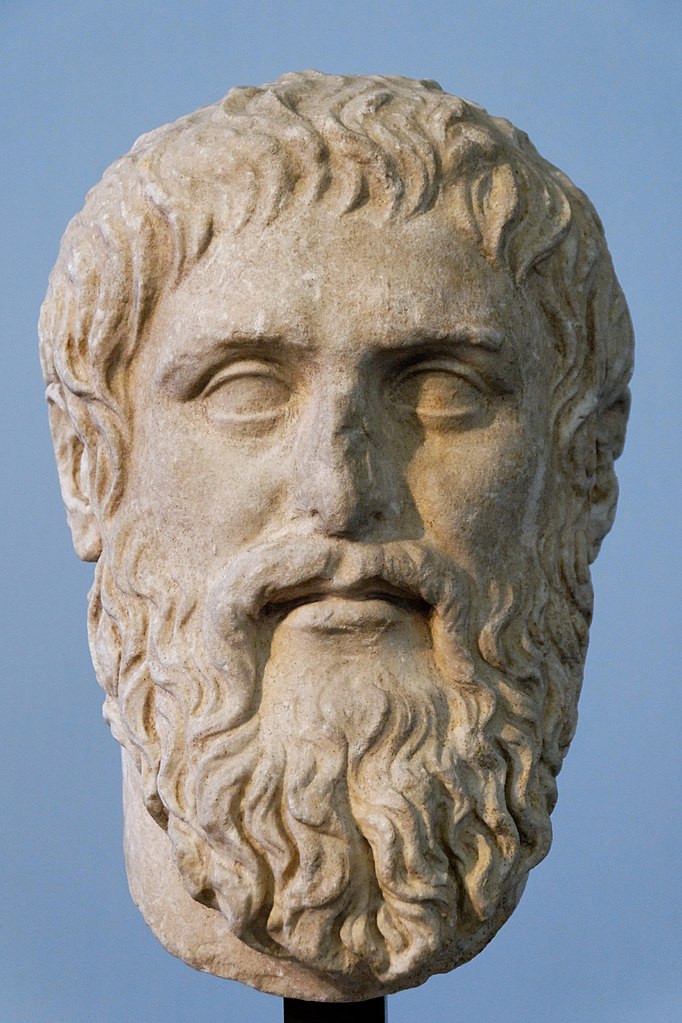

Before the One Ring, created by Sauron during the Second Age, Plato created, as a thought experiment, the Ring of Gyges which gave its wearer the cloak of invisibility. Gyges discovered that when he was invisible, he could commit immoral acts and crimes without suffering any adverse consequences or retribution from society.

Plato in his Republic, using the ring of invisibility as an analogy, explores man’s ability to remain honest and moral in the face of immunity from all consequences. He concludes that if one is free of any consequences he will act in his own self-interest, justice be damned, or as the 19th century historian and writer, Lord Acton states, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

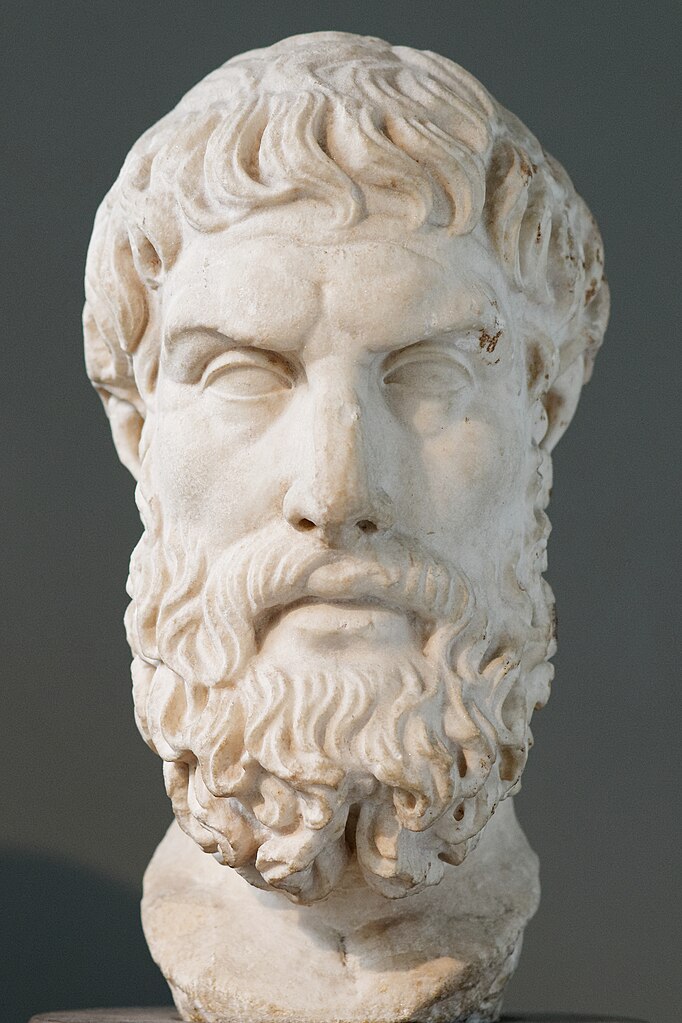

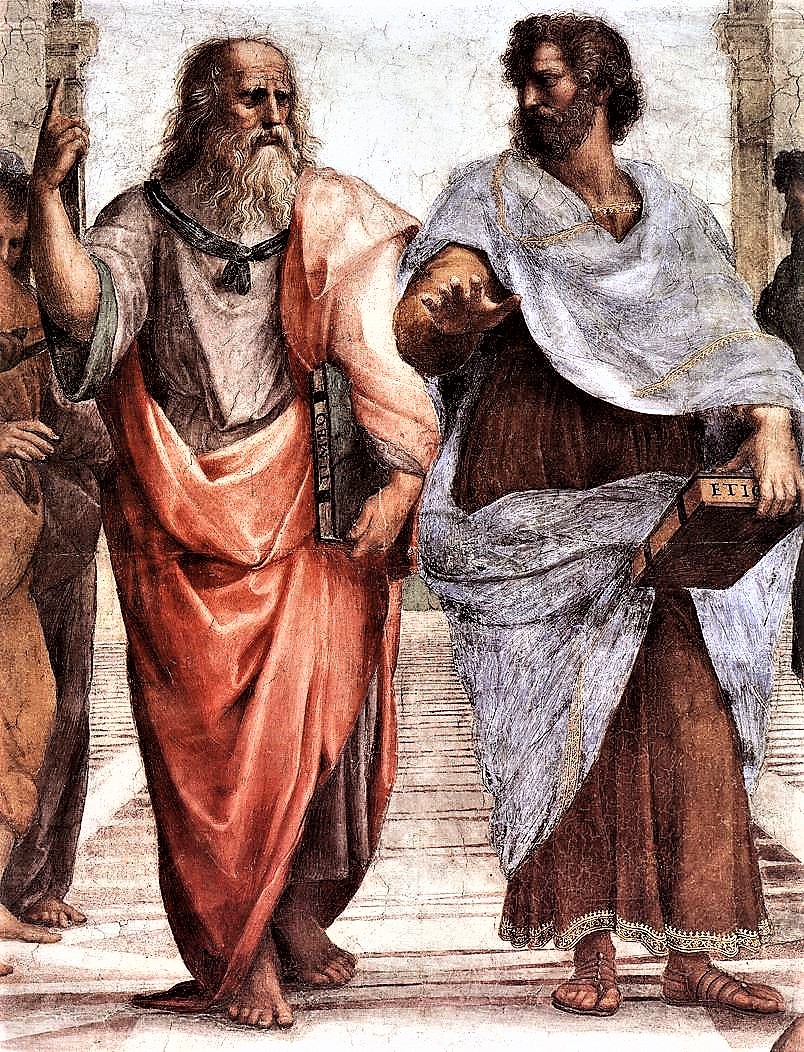

This leads Plato, through the lips of Socrates, to suggest that justice is not a social construct but an inherent quality of one’s soul. The soul must be in harmony with one’s actions and a harmonious soul contributes to a just society. Socrates believed and advised, and he followed his advice, that a harmonious and pure soul leads to true happiness and fulfillment or as the ancient Greeks called it: eudaimonia. For Aristotle eudaimonia is the highest human good and the only human good that is desirable for its own sake, an end in itself. Justice is a by-product of true happiness. Unhappy people and unhappy societies are not just people and just societies.

J.R.R. Tolkien, not only a writer but also a philologist, most certainly was aware of Plato’s Ring of Gyges as an analogy of ultimate power when he used his One Ring in the Lord of the Rings as the definitive symbol of man’s quest to resist and fight evil.

Source: The Republic by Plato. Reason and Meaning.com. Philosophy Terms. Oxford Reference. Graphic: The One Ring, Good Free Photos.