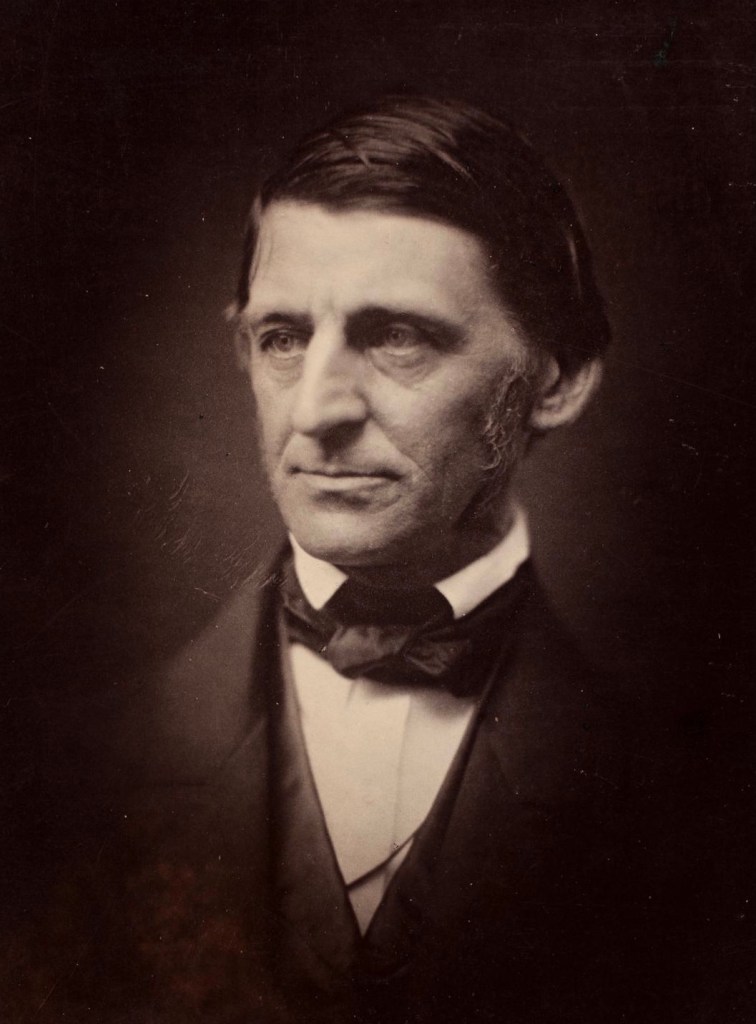

At the end of first year of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC Athenians held the customary public funeral to honor the soldiers who gave their lives in the war against Sparta. As Thucydides records in his “History of the Peloponnesian War” the funeral was a procession of citizens that ushered ten cypress coffins representing the ten Athenian tribes plus one more for the soldiers not recovered from the field of battle to the public graveyard at Ceramicus.

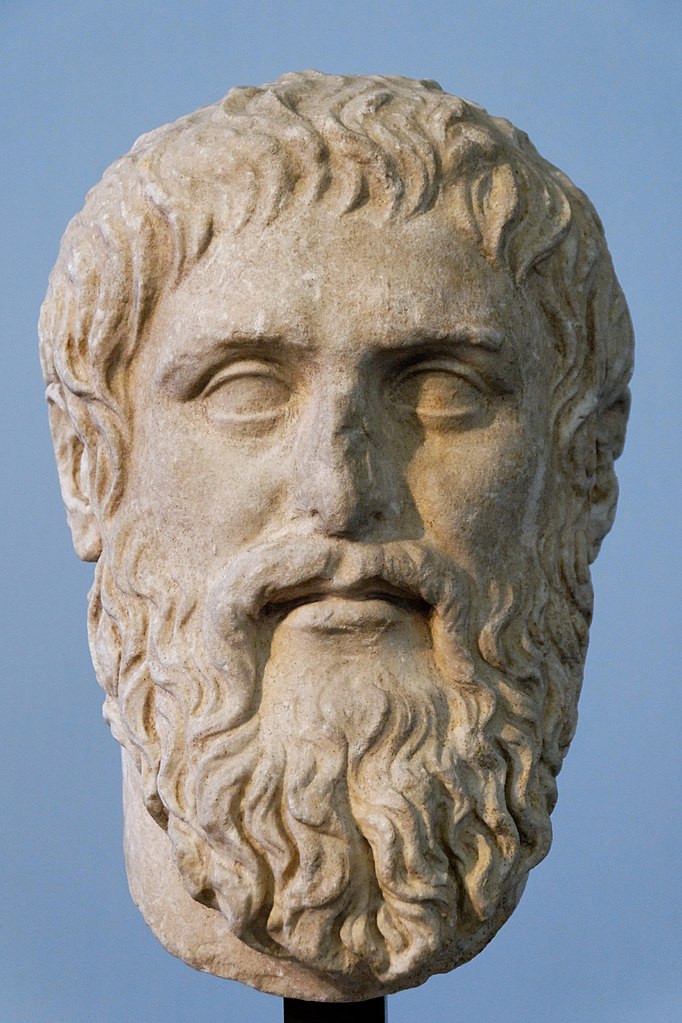

Thucydides further states that “When the bodies had been buried, it was customary for some wise and prudent notable and chief person of the city, preeminent in honor and dignity, before all the people to make a prayer in praise of the dead, and after doing this, each one returned to his House. That time to report the praises of the first who were killed in the war, Pericles, son of Xanthippus, was chosen; who, having finished the solemnities made in the tomb, climbed on a chair, from where all the people could see and hear him, and gave this discourse.”

Pericles’ speech was given not only as a tribute to the fallen, but a celebration of the Athenian citizens’ patriotism and urged them to honor the dead by continued support for the city and its democratic ideals.

The following is the first paragraph of the speech recorded by Thucydides:

Most of those who have spoken here before me have commended the lawgiver who added this oration to our other funeral customs. It seemed to them a worthy thing that such an honor should be given at their burial to the dead who have fallen on the field of battle. But I should have preferred that, when men’s deeds have been brave, they should be honored in deed only, and with such an honor as this public funeral, which you are now witnessing. Then the reputation of many would not have been imperiled on the eloquence or want of eloquence of one, and their virtues believed or not as he spoke well or ill. For it is difficult to say neither too little nor too much; and even moderation is apt not to give the impression of truthfulness. The friend of the dead who knows the facts is likely to think that the words of the speaker fall short of his knowledge and of his wishes; another who is not so well informed, when he hears of anything which surpasses his own powers, will be envious and will suspect exaggeration. Mankind are tolerant of the praises of others so long as each hearer thinks that he can do as well or nearly as well himself, but, when the speaker rises above him, jealousy is aroused and he begins to be incredulous. However, since our ancestors have set the seal of their approval upon the practice, I must obey, and to the utmost of my power shall endeavor to satisfy the wishes and beliefs of all who hear me.

Source: Richard Hooker, 1996, University of Minnesota, Human Rights Library. Graphic: Pericles Funeral Oration by Philipp Foltz, 1877, Public domain.