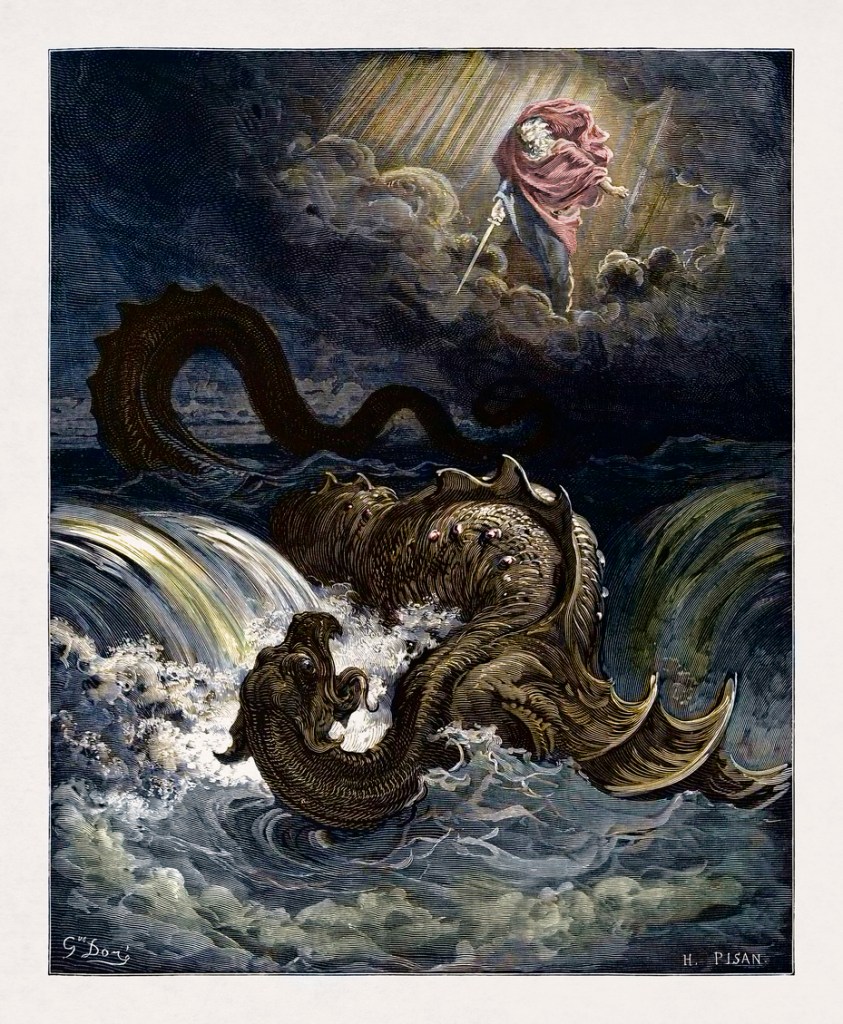

During the Italian Renaissance, a cultural rebirth fueled optimism and propelled civilization to new heights. Yet, in stark contrast, werewolf and witch trials, often culminating in gruesome executions, cast a superstitious shadow over the cold, rugged rural regions of France and Germany from the 14th to 17th centuries.

One notorious case revolves around Peter Stumpp, dubbed the “Werewolf of Bedburg.” In 1589, near Cologne in what is now Germany, Stumpp faced accusations of lycanthropy during a spree of brutal murders and livestock killings. Under torture, he confessed to striking a pact with the devil, who allegedly provided a magical wolf-skin belt that allowed him to transform into a wolf. He admitted murdering and cannibalizing numerous victims, including children. Stumpp’s punishment was as horrifying as his alleged crimes: he was beheaded and burned, alongside his daughter and mistress, who were also implicated. His severed head was later mounted on a pole as a grim public warning.

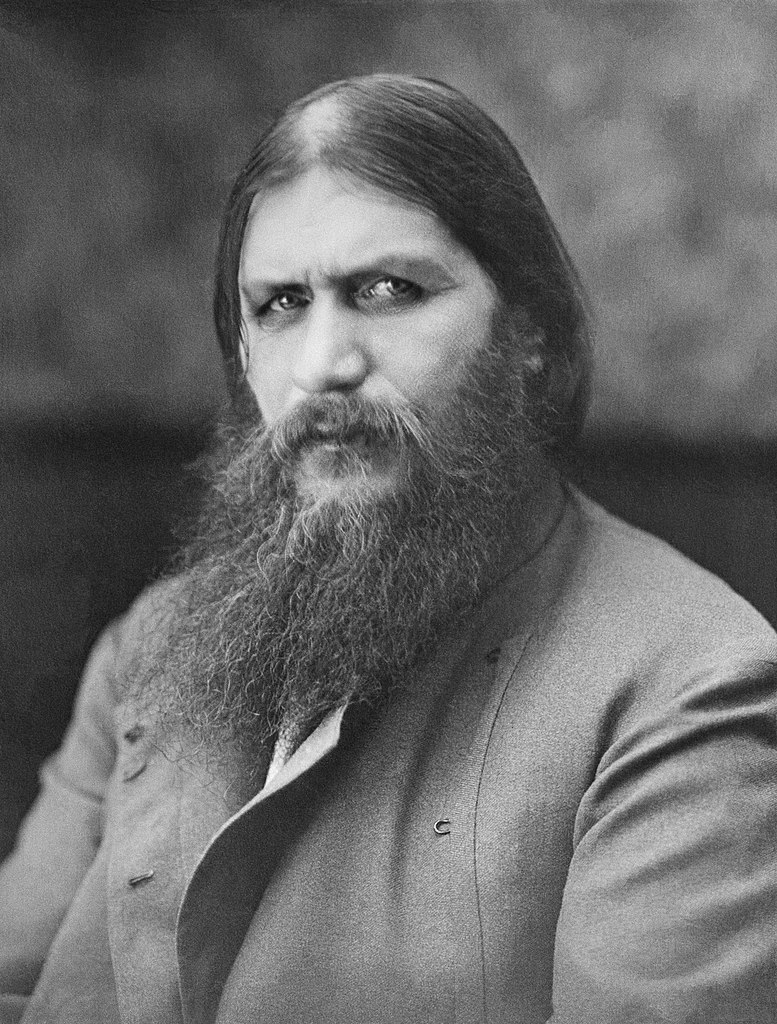

In a striking counterexample, a case from 1692 in present-day Latvia and Estonia challenges the typical narrative. An 80-year-old man named Thiess of Kaltenbrun confessed to being a werewolf, not to wreak havoc, but to protect his community. He claimed he and other “werewolves” battled witches, even journeying to Hell and back to secure the region’s grain supply. The court, skeptical of his tale and possibly viewing him as delusional (perhaps an early case of clinical lycanthropy), rejected the death penalty and sentenced him to flogging instead.

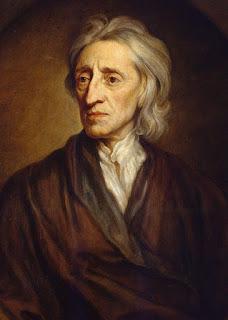

These trials often hinged on confessions extracted through torture, blurring the lines between truth, projection, vengeance, and superstition. Historians still debate the reality behind the accused: Were they serial killers, convenient scapegoats for unsolved crimes, or individuals afflicted by psychological conditions like lycanthropy—a disorder marked by the delusion of transforming into an animal? In his 1865 work, The Book of Were-Wolves, Sabine Baring-Gould analyzed cases like Stumpp’s, arguing that while superstition inflated their legend, they may have been rooted in real incidents: gruesome murders or societal fears run amok.

Source: The Book of Werewolves by Baring-Gould. Werewolf Trials by Beck, History, 2021. Graphic: Werewolf Groc 3.