“To realize one’s destiny is a person’s only obligation.” Paulo Coelho – The Alchemist

Paulo Coelho’s (1947-Present) The Alchemist transcends from the pages of folklore through the dreams of all men of adventure, wrapped into a magical fantasy inhabiting the realm of know thy self, heal thy self, and be true to your heart. A timeless effort instructing all to follow your dreams. Desires anchored in your heart with magic flowing from believing in yourself.

The Alchemist is more than a tale of shepherds, mystics, prophets, treasure, and love, although it is all of that. It is also a parable of craft, trial, and vision. Craft in the tending of flocks, the learning of alchemy, the reading of omens. Trial in the setbacks, the labor, the desert’s unforgiving silence; struggles in the hunger, the fear, the wars of men, and the scourging, scorching winds of sand. Vision in the glimpses of truth, the covenant whispered by the soul, the horizon that calls him onward.

This parable echoes older tales, such as the Arabian fable of the Treasure in Cairo, where a man journeys far in search of riches only to discover that the treasure lies buried at home. Coelho reimagines this motif: Santiago’s pilgrimage across deserts and omens ends with the revelation that the treasure was waiting where his journey began. The outward quest becomes necessary not to find treasure elsewhere, but to transform the seeker so he can recognize the treasure within. Home is where the heart is and the heart decides the home.

A pilgrimage not only to follow one’s heart but to listen to it, to understand it. Santiago’s (the story’s protagonist) journey becomes a sermon on judgment, where each liturgical encounter; whether with King Melchizedek, the master Alchemist, or the desert itself; becomes a sacrament of revelation and growth. Coelho’s prose insists that destiny is assisted from without and whispered from within, but only for those who listen. A supernatural covenant between the soul and the cosmos.

The book’s theology is subtle yet insistent: faith is not blind obedience but a fundamental, obliging trust in the language of the world and the heart. The omens, the desert winds, the alchemy of metals; all are metaphors for the divine grammar that sustains not only existence but fulfillment. To heed them is to participate in a liturgy of creation, where every step toward one’s “Personal Legend” is an act of worship and belonging.

In this sense, The Alchemist becomes a catechism of freedom. It teaches that the sacred is not confined to temple walls but discovered in the marketplace, the caravan, the oasis. Santiago’s quest is a Eucharist of life’s experience, where the bread and wine are transmuted into courage and vision. The philosopher’s stone is not a literal artifact but the realization that the heart, when listened to, is itself the vessel of transformation. And beneath it all runs the mystery of time: not a chain of hours but a circle of presence. As Kahlil Gibran writes, “The timeless in you is aware of life’s timelessness. And knows that yesterday is but today’s memory and tomorrow is today’s dream.” Coelho’s desert is the same; its silence holds eternity; its winds carry both memory and dream. To walk through it is to learn that destiny is not deferred but always unfolding in the eternal now: Kairos versus Chronos.

Coelho plays with the Greek distinction: Chronos, the measured tick of the clock, and Kairos, the opportune, sacred moment: the right time. The novel privileges Kairos: destiny arrives when the seeker is attuned, not when the calendar commands. Dalí’s Persistence of Memory becomes a visual echo of Coelho’s dreamtime: clocks melting into landscape, recurring dreams blurring past, present, and future. Time becomes slippery because the Personal Legend is already inscribed in the Soul of the World; Santiago is not inventing destiny but uncovering what has always been written. Time is not only a circle but a marker of decisions. And Melchizedek, the King of Salem (Jerusalem) in the book says: “And, when you want something, all the universe conspires in helping you to achieve it.” Gaia unbound.

Coelho echoes James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis; the idea that Earth functions as a self-regulating organism. In The Alchemist, this appears as the “Soul of the World,” a spiritual force binding all beings together. Alchemy is ecology: The transformation of lead into gold becomes a metaphor for aligning with this living system. To know the Soul of the World is to participate in its balance, much like Gaia theory’s emphasis on the interconnection of all matter.

Where Lovelock is scientific and Coelho mythic, both insist that life is woven into a larger order. Yet literature also reminds us that this order is fragile: innocence fades, dreams are tested, and the heart must decide whether to yield or to pursue.

Rawlings’ The Yearling reminds us that innocence is fragile, and the loss of romantic but impractical childhood dreams is inevitable. Growing up means carrying grief with dignity, letting go, and accepting life’s new paradigm. In The Alchemist, by contrast, dreams of destiny are not relinquished but pursued. The omens and visions are invitations to act, to listen to the heart, and to follow its call. For the young in flesh, this means courage to begin; for the old in spirit, it means reflection on what was or what might have been.

To follow one’s heart is not merely to dream but to enter a covenant with the cosmos. Craft, trial, vision, and time converge into transformation, and Santiago’s pilgrimage becomes our own. The treasure is both within and without, memory and dream, Chronos and Kairos. To listen is to live, and to live is to worship. Reality becomes divinity. Amen.

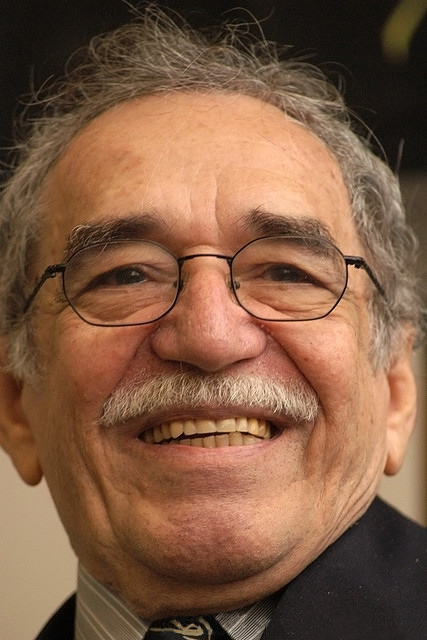

Graphic: Paul Coelho by Ricardo Stuckert, 2024. Public Domain.