The end of the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC marked the end of Athens’ Golden Age. Most historians agree that the halcyon days of Athens were behind her. Some however, such as Victor Davis Hanson in his multi-genre meditations, A War Like No Other, a discourse on military history, cultural decay, and philosophical framing, offers a more nuanced view suggesting that Athens was still capable of greatness, but the lights were dimming.

During the following six decades, after the war, Athens rebuilt. Its navy reached new heights. Its long walls were rebuilt within a decade. Aristophanes retained his satirical edge even if it was a bit more reflective. Agriculture returned in force. Even Sparta reconciled with Athens or vice versa, recognizing once again that the true enemy was Persia.

Athens brought back its material greatness, but its soul was lost. What ended the Golden Age of Athens wasn’t crumbled walls or sunken ships. It was the loss of lives that took the memory, the virtuosity of greatness with it. With them generational continuity, civic pride, and a religious belief in the polis vanished. The meaning, truth, and myth of Athenian exceptionalism died with their passing. The architects of how to lead a successful, purpose driven civilization had disappeared, mostly through death by war or state but also by plague.

Victor Davis Hanson, in his A War Like No Other lists many of the lives lost to and during the war that took much of Athens’ exceptionalism with them to their graves. Below is a partial listing of Hanson’s more complete rendering with some presumptuous additions.

Alcibiades was an overtly ambitious Athenian strategist; brilliant, erratic, and ultimately treasonous. He championed the disastrous Sicilian expedition, Athens greatest defeat. Over the course of the war, he defected multiple times: serving Athens, then Sparta, then Persia, before returning to Athens. He was assassinated in Phrygia around 404 BC while under Persian protection, by, many beleive, the instigation of the Spartan general Lysander.

Euripides though he did not fight in the war exposed its brutality and hypocrisy in his plays such as The Trojan Woman and Helen. The people were not sufficiently appreciative of his war opinions or plays, winning only four firsts at Dionysia compared to 24 and 13 for Sophocles and Aeschylus, respectively. Disillusioned, he went into self-imposed exile in Macedonia and died there around 406 BC by circumstances unknown.

The execution of the Generals of Arginusae remains a legendary example of Athenian arbitrary retribution; proof that a city obsessed with ritualized honor could nullify military genius, and its future, in a single stroke. The naval Battle of Arginusae, fought in 406 BC, east of the Greek island of Lesbos, was the last major Athenian victory over the Spartans in the Peloponnesian War. Athenian command of the battle was split between 8 generals: Aristocrates, Aristogenes, Dimedon, Erasinides, Lysias, Pericles the Younger (son of Pericles), Protomachus, and Thrasyllus. After their victory over the Spartan fleet a storm prevented the Athenians from recovering the survivors, and the dead, from their sunken ships. Of the six generals that returned to Athens all were executed for their negligence. Protomachus and Aristogenes, likely knowing their fate, chose not to return and went into exile.

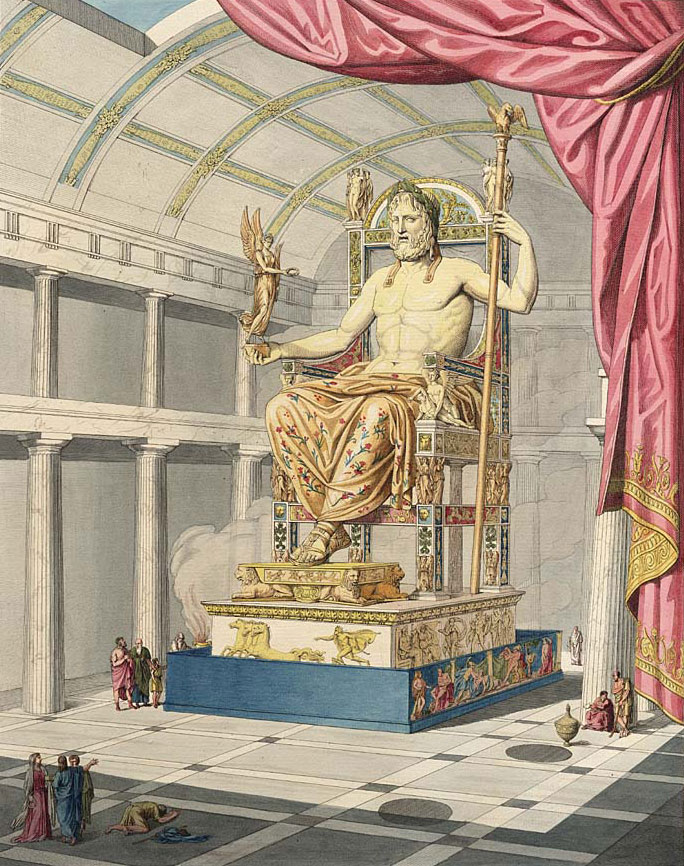

Pericles, the flesh and blood representation of Athens’ greatness was the statesman and general who led the city-state during its golden age. He died of the plague in 429 BC during the war’s early years, taking with him the vision of democratic governance and Athens’ exceptionalism. His 3 legitimate sons all died during the war. His two oldest boys likely died of the plague around 429 BC and Pericles the Younger was executed for his part in the Battle of Arginusae.

Socrates, the world’s greatest philosopher (yes greater than Plato or Aristotle) fought bravely in the war, but he was directly linked to the traitor Alcibiades. He was tried and killed in 399 BC for subverting the youth and not giving the gods their due. That was all pretense. Athens desired to wash their collective hands of the war and Socrates was a very visible reminder of that. He became a ritual scapegoat swept up into the collective expurgation of the war’s memory.

Sophocles, already a man of many years by the beginning of the war, died in 406 BC at the age of 90 or 91, a few years before Athens’ final collapse. His tragedies embodied the ethical and civic pressures of a society unraveling. With the deaths of Aeschylus in 456 BC, Euripides in 406 BC, and Sophocles soon after, the golden age of Greek tragedy came to a close.

Thucydides, author of the scholarly standard for the Peloponnesian War, was exiled after ‘allowing’ the Spartans to capture Amphipolis, He survived the war, and the plague, but never returned to Athens. His History ends in mid-sentence for the period up to 411 BC. He lived till 400 BC, and no one really knows why he didn’t finish his account of the war. Xenophon picked up where Thucydides left off and finished up the war in his first two books of Hellenica which he composed somewhere in the 380s BC.

The Peloponnesian War ended Athens’ greatest days. The men who kept its lights bright were gone. Its material greatness returned, glowing briefly, but its civic greatness, its soul, slowly dimmed. It was a candle in the wind of time that would be rekindled elsewhere. The world would fondly remember its glory, but Athens had lost its spark.

Source: A War Like No Other by Victor Davis Hanson, 2005. Graphic: Alcibiades Being Taught by Socrates, Francois-Andre Vincent, 1776. Musee Fabre, France. Public Domain.