Titus Maccius Plautus was a 2nd century BC Roman playwright known for his loose translations of Greek comedies. It is known that he developed an early attachment to the theater, beginning as a stage carpenter and scene shifter, eventually progressing into acting. During this time, he adopted the nom de plume “Maccius Plautus.” “Maccius” refers to a type of clown, and “Plautus” means flat-footed or bare-footed, thus his name loosely translates to “Titus the Flat-Footed Clown.”

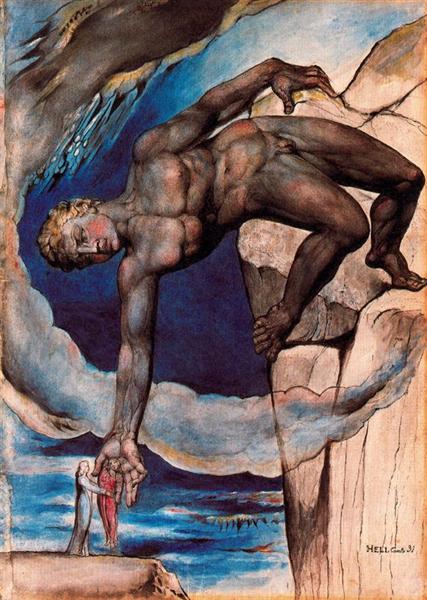

After making some money in the theater, Plautus left the profession, only to lose all his money, forcing him to seek employment in a grain mill. Mill work in ancient Rome was usually reserved for slaves and mules, making it a humiliating job for a free person. However, the drudgery likely provided the motivation for his translation and repurposing of Greek comedies for the Roman audience.

The grind of mill work finds a voice in his plays. Wolfgang De Milo, the current editor and translator of Plautus’s plays for the Loeb Classical Library, states that his plays “…abound in young men doing business abroad and slaves being threatened with being sent to the mill.” While his plays were not strictly original, Plautus incorporated his Italian heritage and customs into his translations of Greek plays, thus making them his own.

Plautus borrowed Greek themes and infused them with his witty take on gods, family, love, money, and immorality. Like the old comedy Greek playwrights, he mocked everything for laughs and urged people to lighten up. His enduring popularity shows that his humor remains timeless and relevant.

Source: Plautus I edited and translated by Wolfgang De Milo, 2011. Graphic: Plautus engraving by Pierre Barrois, 1770, Public Domain