Not every grape is born to be a Cab or Merlot. Not every vine survives the frozen winter’s cold. But, sometimes, you can find a remarkably obscure wine, and you get what you need. (With apologies to the Rolling Stones.)

Wine does not need a household name or worldwide cultivation to leave an impression. Some, from the cracks and corners off the main viticultural beat, fill a glass with a style that beckons notice and draws a grudging nod of respect. Grapes of lesser renown are legion but here we will bow to three worthy of a close encounter. The Amur grape straddling the banks of the thousand-mile Amur River at the intersection of Russia and China; the Saperavi grape of a thousand names, slightly exaggerated, from the rolling Asian hills of eastern Georgia; and the Marquette grape born in the land of a ten-thousand lakes from the test beds of U. of Minnesota.

The Amur grape (Vitis amurensis) is an ancient varietal dating back to pre-Pleistocene times, a survivor at the margins of glaciers and regions of permanent snow and ice. Evolution favored a rootstock capable of withstanding sub-zero winters and the ability to send forth fresh shoots with the swiftness of kudzu covering a Georgia (State) pine, bravely managing the brief, wet summers of floodplains and permafrost.

Its native lavender to deep purple berries yield a full-bodied red wine with subtle aromatics, hinting at dark fruits and recollections of the long-gone boreal forest. The tannins are firm, the acidity cleansing; sharp enough to demand a gentle, sweet companion. Amore mio of chocolate and Amur. I tried a Amur wine in Beijing many years ago and I found it a worthy experience.

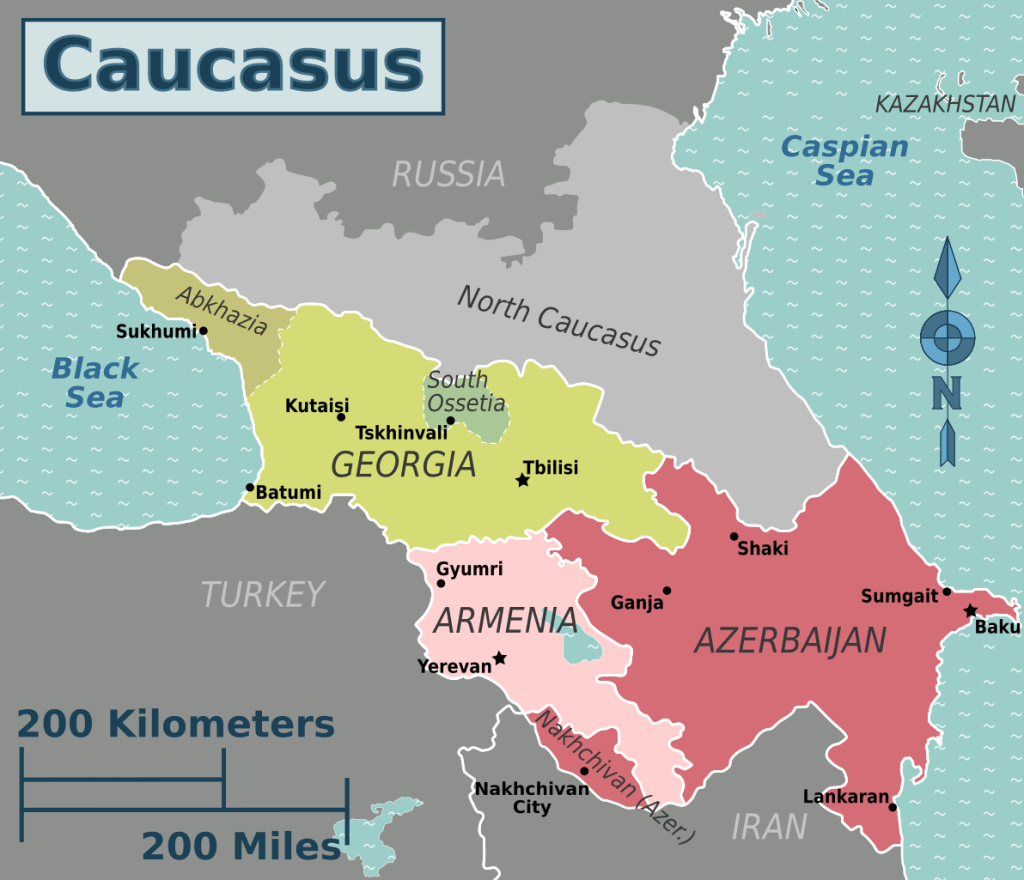

Saperavi (Vitis vinifera) is a rare teinturier grape, its flesh and skin both red, born in the soils newly freed from the retreating glacial ice and snow of southeastern Georgia, nurtured in the cradle of winemaking and civilization. Descended from wild vines cultivated over 8,000 years ago, the spirits and life of Saperavi still retain their vitality in modern times accounting for 30% of its total wine production. Georgians once fermented this varietal in qvevri, (kveh-vree—rhymes with every) egg-shaped clay vessels, dating to the Bronze Age, buried underground, where time, earth, grape, and chemistry converge in a spirited dance of Bacchanalian delight. Though about 10% of Georgian wines still develop in clay, most now age in oak, trading ancestral custom for ease and balance.

Dark as ink in a deep well and high in acidity, Saperavi yields wines that are intense and age-worthy, layered with plum, blackberry, clove, and sometimes a wisp of rising smoke. They range from bone-dry to deliciously sweet, each bottle a tale of terroir and ancestry. Today, the heart of prehistoric craftsmanship still beats in chests of these rugged Caucasus descendants. This wine is hard to find in the U.S., but if you’re in Georgia, try it, just have something sweet nearby to balance its acidity.

Marquette (Vitis vinifera × Vitis riparia, etc.) is a cold-hardy hybrid born in Minnesota in 2006, now finding homes in Vermont and New York. With its ruby hue, medium body, and notes of cherry, blackcurrant, and spice, it evokes a northern acceptance of the land’s tempered gifts. It survives brutal winters, resists disease, and thrives in organic soils that traditional wine grapes often shun. Though oak-aging adds depth, even youthful Marquette wines hold their own. Already, a few notable bottlings hint at its potential. The 2021 La Garagista “In A Dark Country Sky a Whole-Cluster Marquette”, received a rating of 92, described as bold and structured: $43.

Together, this trio of wines form a brave departure from the pack. They are not overt crowd-pleasers, not yet anyway, but a small, short break from tradition can’t be all bad.

Graphic: Amur Grapes, Vitis amurensis, by Andshel, 2015. Public Domain.