I like the quiet.

From the dark, an enigmatic mass of rock and gas streaks inward. Discovered by the ATLAS telescope in Chile on 1 July 2025, it moves at 58 km/s (~130,000 mi/hr), a billion-year exile from some forgotten, possibly exploded star, catalogued as 3I/Atlas. The press immediately fact-checks then shrieks alien mothership. Harvard’s Avi Loeb suggests it could be artificial, citing its size, speed: “non-gravitational acceleration”, and a “leading glow” ahead of the nucleus. Social media lights up with mothership memes, AI-generated images, and recycled Oumuamua panic.

Remaining skeptical but trying to retain objectivity, I ask; is it anything other than a traveler of ice and dust obeying celestial mechanics? And it is very difficult to come up with any answer other than, no.

NASA’s flagship infrared observatory, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) spectra show amorphous water ice sublimating 10,000 km from the nucleus. The Hubble telescope resolves a 13,000-km coma (tail), later stretching to 18,000 km that is rich in radiation forged organics: tholins, and fine dust.

The “leading glow” is sunlight scattering off ice grains ejected forward by outgassing. The “non-gravitational acceleration” is gas jets, not engines. Loeb swings and misses again: ‘Oumuamua in 2017, IM1 in 2014, now this. Three strikes. The boy who cried alien is beginning to resemble the lead character in an Aesop Fable.

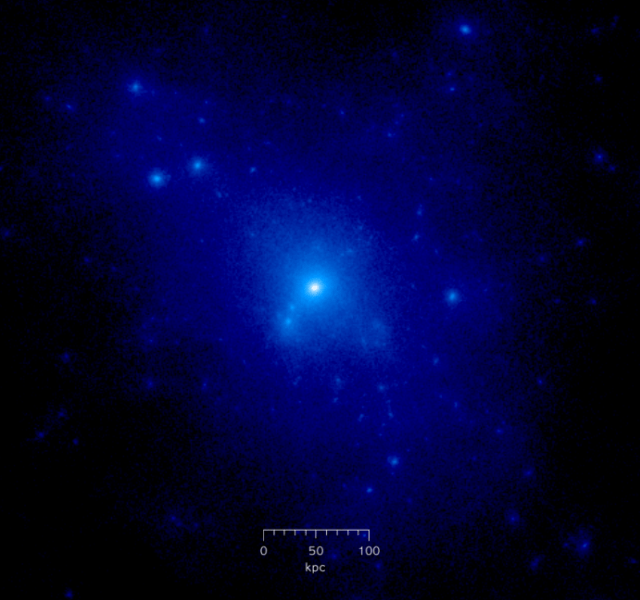

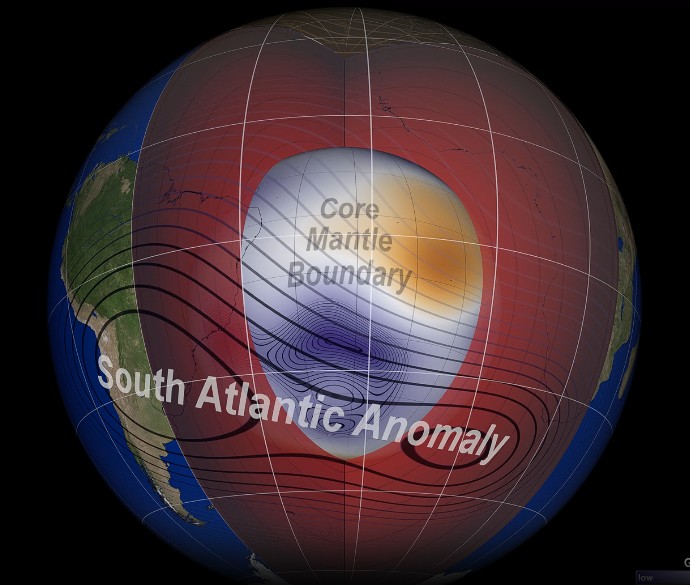

Not that I’m keeping score…well I am…sort of. Since Area 51 seeped into public lore, alien conspiracies have multiplied beyond count, but I still haven’t shaken E.T.’s or Stitches’ hand. No green neighbors have moved next door, no embarrassing probes, just the Milky Way in all its immense, ancient glory remaining quiet. A 13.6-billion-year-old galaxy 100,000 light-years across, 100–400 billion stars, likely most with host planets, and us, alone on a blue dot warmed by a middle-aged G2V star, 4.6 billion years old, quietly fusing hydrogen in the Orion Spur, between the galaxy’s Sagittarius and Perseus spiral arms.

No one knocking. But still, I like the quiet.

An immense galaxy of staggering possibilities, where the mind fails to comprehend the vastness of space and physics provides few answers. The Drake Equation, a probabilistic 7 term formula used to estimate the number of active, communicative extraterrestrial civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy yields an answer of less than one (0.04 to be exact) which is less than the current empirical answer of 1, which is us on the blue dot.

For the show me crowd here’s the Drake Equation N = R* × f_p × n_e × f_l × f_i × f_c × L and inserting 2025 consensus for the parameters: Two stars born each year. Nearly all with planets. One in five with Earth‑like worlds. One in ten with life. One in a hundred with intelligence. One in ten with radio. A thousand years of signal. And the sum is: less than one.

For the true optimist let’s bump up N to 100. Not really a loud party but enough noise that someone should have called the police by now.

No sirens. I like the quiet.

But now add von Neumann self-replicating probes traveling at relativistic speeds, one advanced civilization could explore the galaxy in 240 ship-years (5,400 Earth years). A civilization lasting 1 million years could do this 3000 times over. Yet we see zero Dyson swarms, zero waste heat, zero signals. Conclusion: Either N = 0, or every civilization dies before it advances to the point it is seen by others. That leaves us with a galaxy in a permanent civilizational nursery state, or existing civilizations have all died off before we had the ability to look for them, or we are alone and always have been.

Maybe then, but not now. Or here but sleeping in the nursery. I like the quiet.

But then I remember Isaac Asimov’s seven‑novel Foundation saga. The Galactic Empire crumbles. Hari Seldon’s psychohistory predicts collapse and rebirth. The Second Foundation manipulates from the shadows. Gaia emerges as a planet‑wide mind. Robots reveal they kept it going: Daneel Olivaw, 20,000 years old, guiding humanity. And the final page (Foundation and Earth, 1986) exposes the beginning: Everything traces back to Earth. A radioactive cradle that forced primates to evolve repair genes, curiosity, and restlessness. We are radiation’s children. We didn’t find aliens. We are the aliens.

We are the cradle. We are the travelers. I still like the quiet.