Prolepsis’ Prologue:

The Chorus enters. A single spotlight. A single Damocles’ bullet hangs in the air like a haunted ghost spinning to history’s rhythms and trajectories.

CHORUS:

John Schrank shoots Theodore Roosevelt, 113 long and mostly forgotten years ago, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin on a sharp and chilled Monday, coats pulled tight, 14 October 1912.

That’s the end, my friend, or so it seems. But tragedy demands context, and context demands sacramental passings. Let us reset and reconfigure the scene, with a sentimental barbershop quartet interlude of ‘Moonlight Bay’ drifting in the background and summon the ghosts of campaigns past and the raving refrains of the mad, all served with a bullet.

Act I: The Bull Rising

Before the Bull Moose and the bullet there was tradition and restraint. Before Roosevelt charged up the hill and across the plains, there was McKinley’s calm firmament.

William McKinley, 25th President of the United States, governed with a philosophy of calculated prosperity and protective nationalism, fittingly called the Ohio Napoleon, holding folksy court on America’s front porch. He was deliberate and firm but never rash, he was a Republican loyalist second, leader first, and a quiet expansionist, A Civil War veteran and devout Methodist, McKinley championed high tariffs, the gold standard, and industrial growth as the pillars of American strength.

His first term (1897–1901) unfolded as an economic recovery from Grover Cleveland’s faltering presidency and the Panic of 1893. It was marked by economic stabilization, the Spanish-American War, and the acquisition of overseas territories: Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines, and Hawaii, all additions to America’s imperial structure.

His vice president, Garret Hobart died, of heart failure in 1899 at the age of 55. With no constitutional mechanism to fill the vacancy, the office remained vacant until McKinley’s re-election. It wasn’t until the ratification of the 25th Amendment in 1967 that a formal process was established to replace a vice president.

In 1900, Theodore Roosevelt, then Governor of New York and war hero of the San Juan Hill, was chosen as McKinley’s running mate. His nomination was largely a strategy of containment: an attempt to temper his reformist zeal beneath the inconsequential and ceremonial weight of the vice-presidency.

Act II: Bull Cometh

The Bull Moose was buried beneath ceremony, but symbols cannot contain momentum. The front porch would give way to the lists and charging steeds.

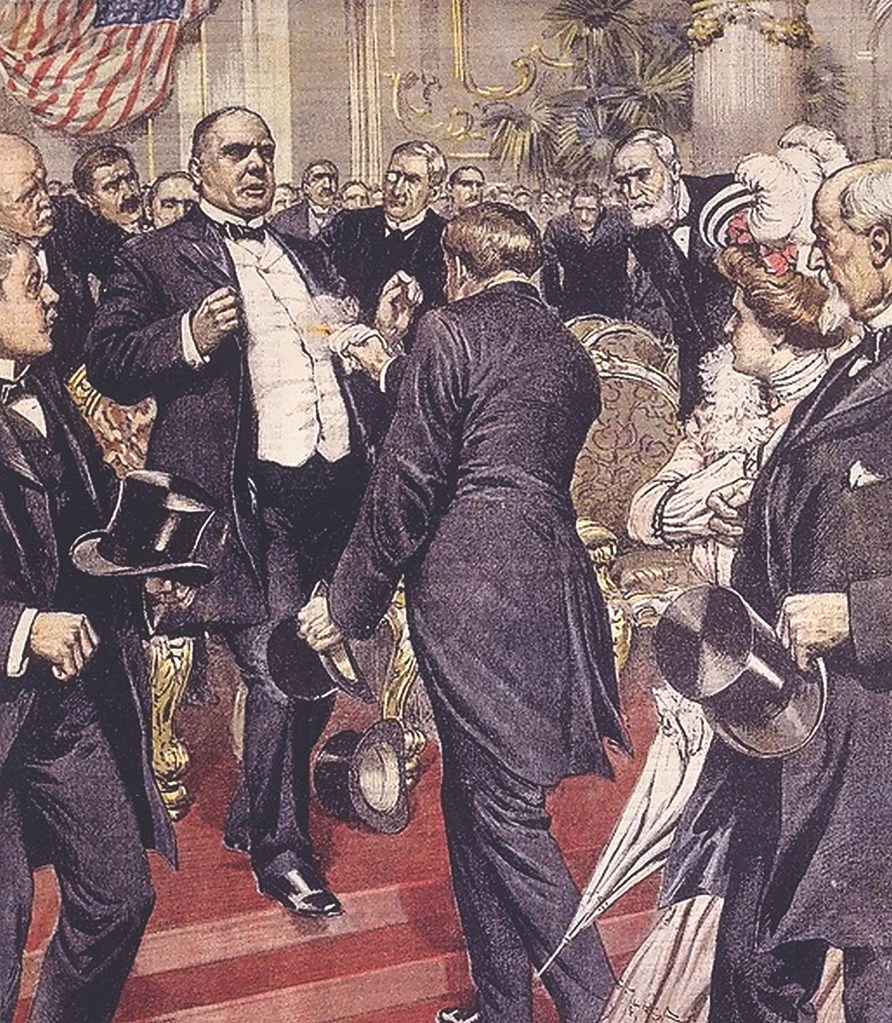

On September 6, 1901, President William McKinley stood beneath the vaulted glass of the Temple of Music at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, an American shrine to progress, electricity, and imperial optimism. There, in the charged glow of modernity, he was shot twice in the abdomen by Leon Czolgosz, a Polish American self-declared anarchist and bitter subject of the Panic of 1893 and its resultant mill closures, strikes and wage collapse, etched into his disillusioned psyche.

Czolgosz had been baptized in the radical writings of Emma Goldman, a Lithuanian emigree and firebrand of the American radical left. Goldman championed anarchism, women’s rights, and sexual liberation. She founded Mother Earth, a journal that became an infamous intellectual hearth for dissent and revolutionary analysis.

To Czolgosz, Mckinley was the embodiment of oppression: capitalism, imperialism, and state violence. His answer to these perceived provocations was violence. Concealing a revolver wrapped in a handkerchief, he fired at close range during a public reception, just as McKinley extended his hand in welcome.

Initially, doctors believed McKinley would recover. But gangrene developed around the damaged pancreas, and he died on 14th of September. His death was slow and tragic, a symbolic collapse of the front porch presidency.

Roosevelt, just 42, stepped up and became the youngest president in U.S. history (JFK was 43). With containment at an end, the Bull broke loose. And he mounted the stage with an agenda.

Act III: The Charge of the Bull

The Bull builds a protective legacy of words and stick, sweat and blood.

Roosevelt’s early presidency honored McKinley’s legacy: trust-busting, tariff moderation, and economic expansion. But he soon added his own signature: conservationism, progressive reform, and a bold, moralistic foreign policy.

He preserved 230 million acres of public land and established the U.S. Forest Service, 5 national parks, 18 national monuments, 150 national forests and a constellation wildlife refuges. Stewardship of the land became a sacred ideal that continues to present day.

In foreign affairs, Roosevelt extended the Monroe Doctrine with his Roosevelt Corollary (1904), asserting that the U.S. had the right to intervene in Latin America to prevent “chronic wrongdoing.” It was a doctrinal pivot from passive hemispheric defense against European imperialism to active imperial stewardship, cloaked in the language of civilization and order. America became the self-appointed policeman of the Western Hemisphere.

The corollary was a response to incidents like the 1902 Venezuelan debt crisis where European navies blockaded ports to force repayment. In Cuba, unrest was quelled with U.S. troops in 1906. Nicaragua, Haiti, and Honduras saw repeated interventions to protect U.S. interests and suppress revolutions. If Latin American failed to maintain order or financial solvency, the U.S. would intervene to stabilize rather than colonize.

The doctrine justified the U.S. dominance of the Panama Canal and set the precedent for Cold War interventions, neutralizing the American back yard while containing Soviet expansion in the east.

Act IV: Hamlet in Milwaukee

Heads of kings rest uneasy. Ghosts of injustice haunt. Princes fall prey.

After winning a full term in 1904, Roosevelt honored his promise not to seek reelection in 1908. But disillusioned with his successor, William Howard Taft, Roosevelt returned to politics in 1912, forming the Progressive Party, nicknamed the Bull Moose Party.

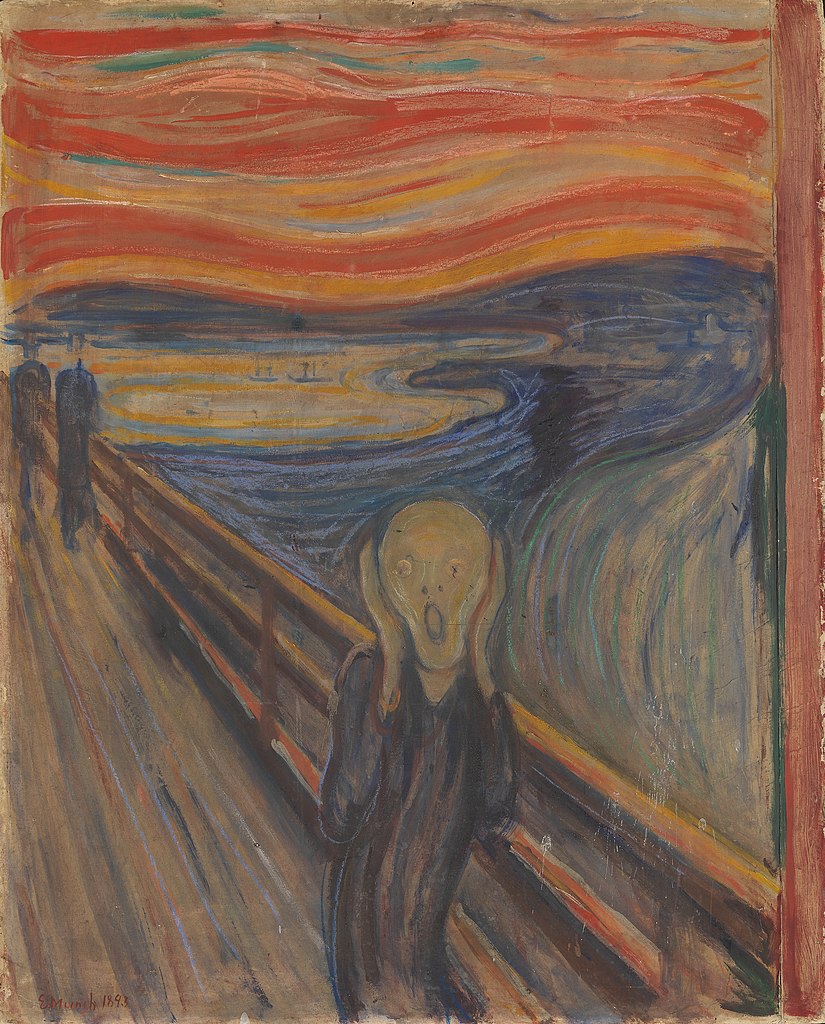

Enter stage left, John Schrank, a former barkeep plagued by visions and imagined slights. In the early morning hours of 15 September 1901, 6 days after McKinley was shot and 2 days before he died, the bar tender dreamt that the slain President rose from his casket and pointed to a shrouded figure in the corner: Roosevelt. “Avenge my death”, the ghost spoke. Schrank claimed to forget the dream for over a decade, until Roosevelt’s bid for a third term in 1912 reawakened the vision, which he now interpreted as a divine command.

Schrank believed Roosevelt’s third-term ambition was a betrayal of American tradition set forth in Washington’s Farewell Address. He hated Roosevelt and feared that he would win the election, seize dictatorial power, and betray the constitutional republic. In his delusional state, he believed Roosevelt was backed by foreign powers and was planning to take over the Panama Canal; an anachronistic fear, given total U.S. control of the canal since 1904. Schrank interpreted the ghost’s voice as God’s will: “Let no murderer occupy the presidential chair for a third term. Avenge my death.”

At his trial for the attempted assassination of Roosevelt, Schrank was remanded to a panel of experts to determine his mental competency. They deemed him insane, a “paranoid schizophrenic”, in the language of the time. He was committed to an asylum, where he remained until his death 31 years later.

Schrank’s madness parallels the haunted introspection of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. Shakespeare’s longest and most psychologically complex tragedy that revolves around a ghost’s command: “Revenge my foul and most unnatural murder.” Hamlet, driven by the specter’s charge, spirals into feigned (and perhaps real) madness, wrestling with betrayal, duty, mortality, and metaphysical doubt. His uncle, the murderer, has married his mother; an Oedipal inversion within the world’s most enduring tragedy.

On 14 October 1912, as Roosevelt stood outside Milwaukee’s Gilpatrick Hotel, Schrank stepped forward and fired. The bullet pierced his steel glasses case and a folded 50-page tome of a speech, slowing its path. Bleeding, a bullet lodged in his chest, Roosevelt refused medical attention. He stepped onto the stage and spoke for 90 minutes, although it is said that due to his loss of blood, he shortened his speech out of necessity. Whether for himself or the audience is lost to history.

Unlike Hamlet, who dithers and soliloquizes his way toward a graveyard of corpses, Schrank shoots, hits, and leaves Roosevelt standing. Hamlet’s tragedy ends in death and metaphysical rupture. Schrank’s farce begins with the demands of a ghost and ends with a 90-minute speech. One prince takes his world with him into death. The other absorbs a bullet and keeps talking.

Act V: Ghosts and Republics

Ghosts and Republics are ephemeral. At the end of time; those fleeting moments, short and long; some, as Proust says, more and more seldom, are best treated with humor and grace.

In tragedy and near calamity, a man’s soul becomes visible. Some are seen darkly, others, bright, clear, unshaken and unafraid of new beginnings even if that beginning is death.

Roosevelt had already charged up San Juan Hill, bullets and fragments whistling past like invitations to a funeral ball. Each a death marker. So, when a solitary bullet from a madman struck him in Milwaukee, it was merely an inconvenience. He quipped: “Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible. I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot, but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.”

Sixty-eight years later, Reagan too survived a bullet to the chest. As he was wheeled into the emergency room at George Washington University Hospital, he said he’d “rather be in Philadelphia,” a throwback to his vaudeville days, a gag line used on fake tombstones: “Here lies Bob: he’d rather be in Philadelphia.” W.C. Fields once requested it as his epitaph. He’s buried in California. To the surgeons, Reagan added: “I hope you’re all Republicans.”

Where Roosevelt offered mettle, Reagan offered mirth. Both answered violence with theatrical defiance: natural-born and unshakable leaders, unbothered by the ghosts that tracked them.

They were not alone. Jackson, beat his would-be-assassin with a cane. Truman kept his appointments after gunfire at Blair house. Ford faced two attempts in seventeen days and kept walking. Bush stood unfazed after a grenade failed to detonate. They met their specters with grace, a joke, and a shrug.

The assassins and would-be assassins vanished into the diffusing whisps of history. The leaders of men left a republic haunted not by ghosts, but by a living memory: charged with the courage to endure and to imagine greatness.

Graphic: Assassination of President McKinley by Achille Beltrame, 1901. Public Domain.