Maybe there’s nothin’ happenin’ there

Or maybe there’s somethin’ in the air — John Hiatt – Memphis in the Meantime

The operation in Caracas did not inaugurate a new doctrine so much as enforce an old one: The Monroe Doctrine or as the new moniker that is sweeping social media: The Don-roe Doctrine, The DDs. It demonstrated that, when the United States chooses to act in its near abroad, it can do so quickly, decisively, and without the prolonged escalation that once defined hemispheric interventions. The speed mattered less than the silence that followed.

What stretches south from the U.S. southern border is not a collection of isolated states so much as a single basin of changing fortunes. A shared space of currents and constraints where energy, food, money, people, and power circulate unevenly. In that basin, geography compresses time, stretching from long somnolence to sudden, decisive action in prestissimo. Decisions made in one port quickly reverberate into another; scarcity in one system bleeds into the next. When a major node fails, the effects do not remain local, they resonate in a loose, syncopated jazz time

The removal of Venezuela as a patron did not merely end Maduro’s dictatorship, it likely altered the flow of reality in the basin itself. What followed from adjacent confines and distant hegemons alike was not immediate confrontation but boilerplate as hesitancy or visa-versa. Borders were secured. Procedural condemnations were issued. The United Nations will hear of this! Behind the statements, positions were analyzed and reassessed. Cards were checked. No one raised. Everyone counted their chips. Everyone kept their cards, except Maduro, but no one pushed the pot.

In the meantime: the basin holds it breath, the alternatives have no luster, and time has taken on a velocity beyond the speed limits of the usual diplomatic stall. In the basin, survival at all costs no longer promotes stability of government nor docility of the populace. In the basin, the strength of will is now measured in meals, watts, and months: maybe. The Venezuela operation lasted 3 hours.

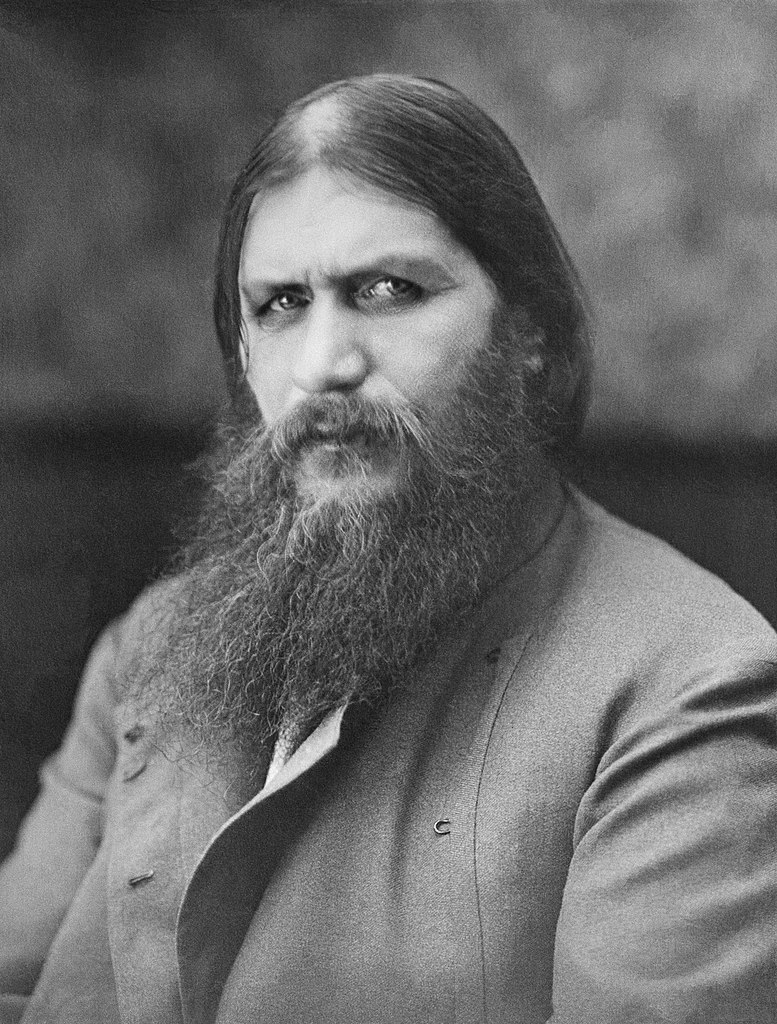

The absence of a Venezuelan military effective response was not the lack of detection of the opposing force or bribery of key personal to look the other way. It was the predictable outcome of a hollowed-out command structure confronted more attuned to loyalty rather than ability. Selective strikes against decision‑making nodes, combined with degraded communications and uncertainty about leadership status, collapsed the chain of authority before it could cohere into action. In a system likely conditioned to await orders from the top rather than exercise initiative, paralysis was the rational response. No one bucks the top…North Korea redux. A thirty‑minute operation leaves no room for deliberation; it ends before the system can decide what it is seeing. Maduro wasn’t answering his phone.

And the operation was not just the removal of a bad actor; it was also about who was watching.

The Iranian strike was never just a counter‑proliferation exercise. Reducing nuclear capability was the mechanism, not the message. The message was capability itself. It was designed to be seen not by Tehran, which already understood the risks, but by Moscow and Beijing. The flight profiles, the munitions used, the coordination, the timing, the public naming of the operation, all of it communicated U.S. reach, patience, and the ability to act unilaterally at scale without triggering uncontrolled escalation. It was deterrent by demonstration, not a declaration for further action.

The Venezuela operation carries the same scent, even if the target is less world‑ending. Different theater, different tools, same audience. There were other tells. In Moscow, state‑adjacent channels reverted to cultural filler, Swan Lake on shortwave. A gesture with a long memory. In Russian political language, it has historically marked moments of uncertainty at the top: authority suspended, clarity withheld, everyone instructed to wait. It was not a declaration, but it was not nothing either. Less foreknowledge than recognition. An acknowledgment that something irreversible was unfolding, inferred from U.S. posture rather than anything concrete.

That recognition itself would not have gone unnoticed. Intelligence services watch each other as closely as they watch targets, and awareness on one side becomes signal on the other. A brief pause, publicly attributed to weather or timing around the holidays, need not imply any hesitation. It can just as easily reflect confirmation: that inference had not translated into possible interference, that compromised channels would remain compromised, and that recognition would stay passive. In that sense, the music was not a warning, and the delay was not a feint. Both were acknowledgments that the hand had changed, and that no one intended to show their cards before the next move was made.

The unrest in Iran reads differently. Less recognition than diversion. When leverage is limited in one theater, pressure migrates to another. Iran’s internal volatility has long been a known fault line. One where agitation carries asymmetric cost. Disruption there absorbs Iranian authorities’ attention, resources, and narrative bandwidth, reducing the capacity for coordinated response elsewhere. Whether by design or exploitation, the effect is the same: consequences are diluted across theaters rather than concentrated at the point of action. Hezbollah and Hamas in the Caribbean remain isolated and neutered.

This does not require coordination to function. Systems under strain respond predictably to stress applied at their weakest seams. Iran’s unrest filled the information space with noise at precisely the moment clarity elsewhere would have been costly.

In Venezuela, the point wasn’t regime change as an ostentatious show of force or a shot across the bow. It was proof of access, intelligence dominance, and decision‑speed inside a space long assumed to be cluttered with foreign influence. The absence of a name matters. So does the brevity. So does the lack of follow‑on rhetoric, which, for Trump, is really saying something.

Regional reactions reflected this reality. The message, delivered without verbiage, was understood immediately. Except in Congress. Colombia’s troop movements were defensive and stabilizing, aimed at spillover rather than confrontation. Mexico and Colombia’s appeals to multilateral condemnation preserved diplomatic cover without altering facts on the ground. China and Russia issued ritualized objections. Entirely predictable, restrained, and notably unaccompanied by action. Iran’s rhetoric filled space where leverage was absent. Across the board, states assessed their stacks of chips and chose not to raise.

This collective hesitation revealed the deeper shift. The Caracas operation likely removed Venezuela as a structural patron and sanctuary, not just a regime. That removal matters less for ideology than for logistics. It collapses the external framework that allowed other systems: most notably Cuba, to remain in the game, even without chips.

Cuba’s predicament is not strategic; it is temporal and tactical. The island lacks indigenous energy beyond biomass, cannot sustain its grid without imported fuel, and faces chronic food insecurity dependent on foreign exchange. Its export of human capital: doctors, engineers, security personnel, once generated influence and cash, but those returns have diminished, and the population left behind is aging and shrinking. Tourism and remittances no longer provide reliable buffers. Scarcity does not need to become catastrophic to destabilize a system; it only needs to become unpredictable. Revolution is three meals away.

In this context, the familiar options narrow. Refusal to accept the obvious with re-engerized brutality can delay outcomes but the path ahead remains the same. Partial opening risks unleashing forces that cannot be re-contained. A managed transition preserves continuity but requires acknowledging mistakes and ultimately exhibiting weakness. Waiting for the irrational rescue likely recreates Ceausescu execution at the hands of an exhausted populace. Time is now a luxury. And there is no Che Guevara left to pretend this is about anything other than power.

The broader hemispheric picture reinforces this compression. Panama’s strategic assets favor quiet realignment rather than confrontation. Colombia’s incentives point toward containment. Mexico’s long‑standing safety valves, outward migration and remittance flows, have narrowed as borders tighten and returns increase. At the same time, cartel finances face pressure from heightened surveillance, financial enforcement, and disrupted logistics. When money tightens, patience evaporates. Ambiguity and neutrality become expensive.

The external powers, beyond the basin, face their own constraints. Russia’s tools in the hemisphere are limited to smoke signals, narrative, and opportunistic cyber and communication disruption; it cannot project sustained force near U.S. logistics without unacceptable risk. China’s leverage is financial and infrastructural: think Peru’s deepwater port, but money loses persuasive power when leaders weigh it against personal liability. Loans cannot guarantee immunity. Infrastructure cannot extract individuals from collapsing systems. A Berlin‑style airlift to sustain Cuba is implausible: geography, energy requirements, and visibility make sustained resupply untenable without escalation. A step that neither Beijing nor Moscow appear willing to risk.

What emerges instead is a less noisy contest. The real currency becomes safe passage for the unwanted and the management of transitions rather than bids for loyalty. Ports, telecom, finance, and migration policy, to and from the U.S., become the levers. Intelligence exploitation encourages action against cartels, rolling up networks of crime rather than staging battles.

In this environment, public speeches matter less than demonstrated capability. Respectful language toward leaders paired with relentless focus on non‑state threats: cartels, preserves diplomatic niceties while narrowing the options. The message is conveyed not through ultimatums but through persistence: neutrality becomes costly; alignment allows for tomorrows.

The western hemisphere has entered a meantime: not a moment of dramatic conquest, but a period where waiting is the most dangerous strategy. Outcomes will be shaped less by declarations than by which pressures are allowed to accumulate, and which are relieved. The Caracas operation did not end the game; it thinned the table and moved the stakes to the final table.