“The notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice, have there no place. Where there is no common power, there is no law; where no law, no injustice.” — Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes saw human nature as a cauldron of chaos. In his state of nature, life is “nasty, brutish, and short,” a “war of all against all” where self-preservation is the only natural law. Shaped by Thucydides’ tales of strife and Machiavelli’s ruthless pragmatism, Hobbes cast man’s self-interest as a destructive force that casts morality aside. His remedy to avert chaos: a towering sovereign, ideally a monarch, to crush anarchy with an iron fist. The social contract trades liberty for security, forging laws as human tools to bind the beast within. Yet Hobbes stumbled: he failed to grasp power’s seductive pull. He assumed his Leviathan, though human, would rise above the self-interest he despised, wielding authority without buckling to its corruption.

“Reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind…that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions.” — Second Treatise of Government by John Locke

John Locke painted a gentler portrait of man than did Hobbes. He rooted natural law in reason and divine will, granting all people inherent rights to life, liberty, and property. His state of nature is peaceful yet imperfect, marred by the “want of a common judge with authority,” leaving it vulnerable to human bias and external threats. Optimistic, Locke envisioned a social contract built on the consent of the governed, protecting these rights through mutual respect and laying the groundwork for constitutional rule. Where Hobbes saw a void to be filled with control, Locke trusted reason to elevate humanity, crafting government as a shield, not a shackle.

Hobbes and Locke clash at the fault line of power. Hobbes’s sovereign, meant to tame chaos, reflects the rulers’ thirst for dominance, but his naivety about power’s effect cracks his foundation. Locke’s ideals, morality, reason, rights, empower the ruled, who yearn for liberty after security sours. Hobbes missed the flaw: rulers, driven by the same self-interest he feared, bend laws to their will, spawning a dual reality—one code for the governed, another for the governors. Locke’s vision of freedom and limited government inspires their soul, while Hobbes’s call for order fortifies their bones with courts, police, and laws of men. The U.S. Constitution marries both, yet scandals tip the scales: power corrupts, and liberty frays as safeguards buckle under the rulers’ grip.

Hobbes and Locke both accept the imperfection of man but take different paths to mitigate that imperfection with workable safeguards. Hobbes insists on the rule by law but drafted by imperfect man and applied with a Machiavellian indifference with no solution for absolute powers corrupting influence. Locke also chooses to rule by law but guided by morality, God and the will to depose of despots.

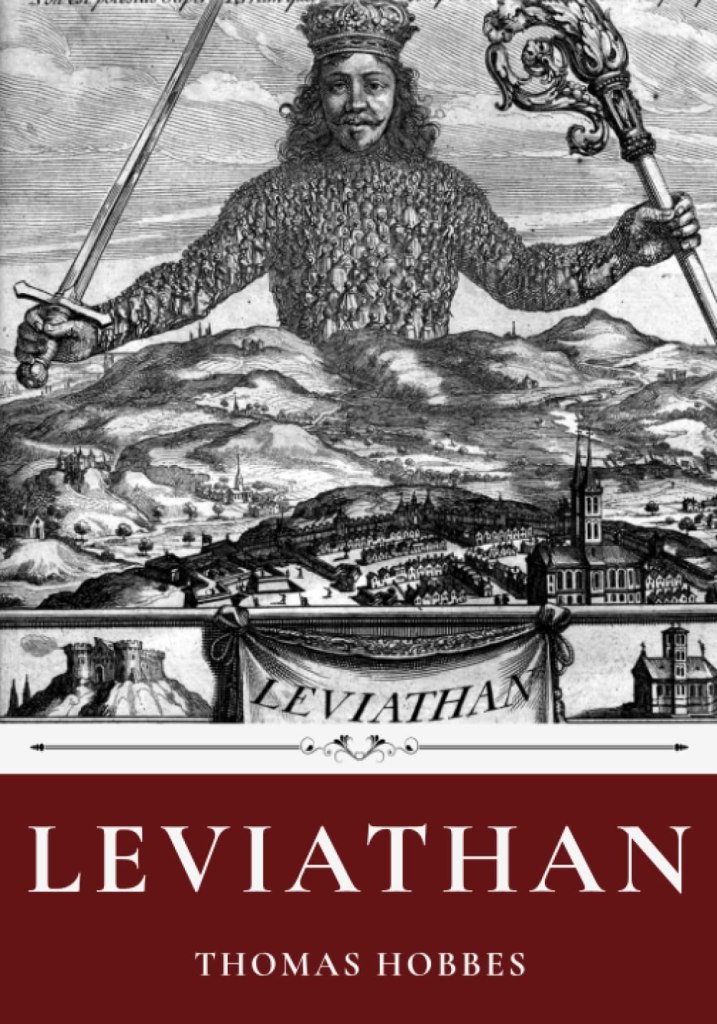

Sources: Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes; Second Treatise of Government, John Locke. Graphic:Original Leviathan frontispiece, a king composed of subjects, designed with Hobbes’s input.