Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which includes gravity, predicts that black holes have a tricky feature: a singularity. This is a point where space and time are squeezed so tightly that the laws of physics break down—think of it as a cosmic “error message.” To fix this, scientists often turn to exotic matter—hypothetical substances with bizarre properties like negative energy—to smooth things out. However, a team from the University of Barcelona, led by Pablo Bueno, found an alternative. They didn’t need exotic matter at all. Instead, they tweaked Einstein’s gravity by adding an infinite series of extra “rules” (higher-curvature corrections) to the math.

Their solution works in spacetimes with more than four dimensions—beyond our usual height, width, depth, and time. In these higher-dimensional worlds, black holes can exist without singularities. This “smooths out” black holes, making them less mysterious and more like regular objects in spacetime—no weird stuff required.

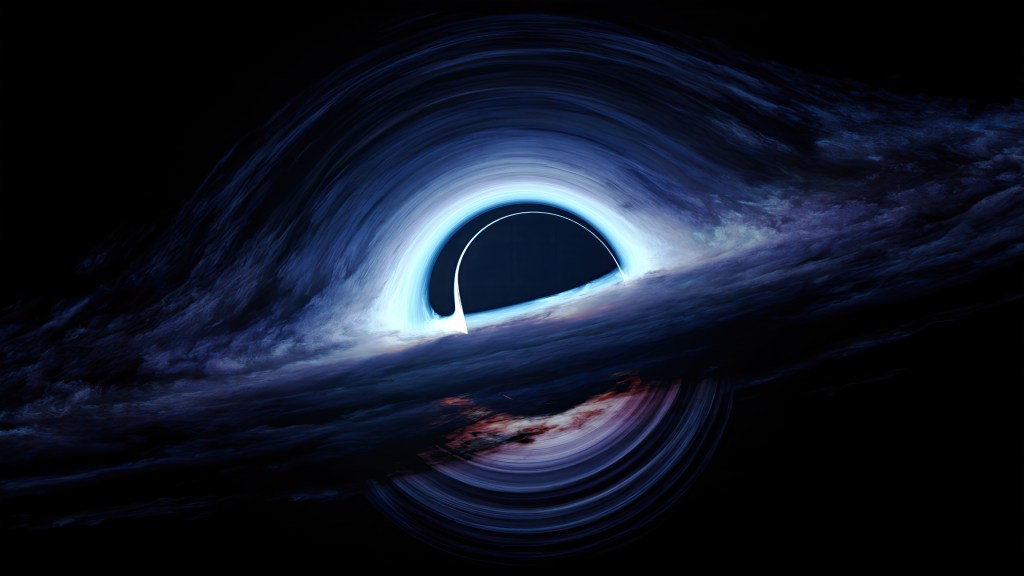

The presence of extra dimensions doesn’t just fix singularities—it can also change how black holes behave. In higher-dimensional spacetimes, black holes might have different event horizon shapes (the boundary beyond which nothing escapes) or other structural quirks. The Barcelona team’s work shows that these altered properties emerge naturally from gravity in more than four dimensions, offering a fresh perspective on these cosmic giants.

Thinking outside the box, is it possible that these extra dimensions link black holes to “a reality outside regular spacetime,” like wormholes (tunnels through spacetime), braneworlds (parallel universes on higher-dimensional “membranes”), or even gateways to white holes (theoretical opposites of black holes that spit stuff out)? Theories like string theory and braneworld scenarios suggest that extra dimensions might allow such connections. For example, a wormhole could theoretically bridge two distant points in our universe—or even lead to a completely different universe.

While the math of higher dimensions opens the door to these possibilities, it’s all conjecture. The Barcelona team’s work is a major step forward in understanding black holes in higher dimensions, but it doesn’t directly prove connections to other realities.

Source: Grok 3. Regular Black Holes… by Bueno, P. et al., Physics Letter B, February 2025. Graphic: Black Hole Rendering, iStock licensed.