By 1881, literature was shifting, Realism’s clarity giving way to Modernism’s psychological fog. Henry James pioneered the transformation, publishing what many hailed as his masterpiece and others found nearly unreadable. He moved from the crisp windows of Daisy Miller and Washington Square, where social dilemmas are transparent, into the labyrinth of The Portrait of a Lady, a slow, meandering narrative that tested patience to the point of exasperation. James stretched his scenes into long psychological dramas, shadowed by melancholy, lingering on minutiae rather than decisive events. To admirers, this was a profound exploration of consciousness, to detractors, a soporific feast of abstraction.

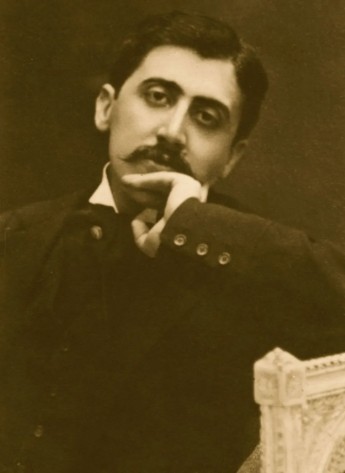

Where James’s Portrait is a punishing fugue of memory and angst, a darkness at the edge of noon, Proust’s Swann’s Way (1913) offers a sensual slow dance of lush detail, playful childhood games, and adult desire. In Combray, the family had two ways to take their walks: the short way and the long way. The short way was familiar, contained, offering scenery but little transformation. The long way was expansive, expressive, full of detours and revelations. In Swann in Love, the same pattern unfolds: the first half is Swann’s descent into desire, the short way of immediacy; the second half is his struggle to free himself, the long way of disillusionment and reflection. For Proust, the long way is where life’s lessons are held. Meaning is not found in shortcuts but in detours, delays, and the endurance of memory. The long way is the design of his art: winding detours that illuminate the search for lost time.

Wilde enters here as counterpoint. Where Proust lingers in digressive glow, Wilde sharpens language into bite. His wit distills the same metaphysical concerns: beauty, desire, memory, decay, into crystalline aphorisms. Wilde’s sentences are daggers wrapped in velvet, each polished to a point. If Proust is the cathedral of memory, Wilde is the mirror that cuts as it reflects. The Picture of Dorian Gray dramatizes the peril of desire and the corruption of beauty; themes Proust refracts through memory and longing. But Wilde compresses the ineffable into epigram: glow against bite, long way against short.

Cinema, now, becomes the continuance of these styles. Wilde’s paradox and Proust’s memory echo in films as diverse as Spectre (2015), No Time to Die (2021), and Gosford Park (2001). In Spectre, Madeleine Swann, a psychologist whose very name invokes Madeleine tea cakes and Swann’s Way, probes Bond’s past like Proust probing consciousness, turning trauma into narrative. In No Time to Die, desire and mortality entwine, echoing Proust’s meditation that “life has taken us round it, led us beyond it.” And in Gosford Park, Sir William McCordle brushing crumbs from a breast, Swann brushing flowers from a bosom, gestures lifted from Proust’s sensual triggers, collapse time into desire, while Altman’s upstairs-downstairs satire mirrors Wilde’s social wit. These films remind us that both the glow and the bite, the long way and the short, remain inexhaustible. The short as overture, the long as movement. One as a flash of life, the other as the light of experience.

James stretches narrative into labyrinthine difficulty. Proust redeems patience with memory’s illumination. Wilde polishes language into paradoxical brilliance. Chaplin, in Modern Times (1936), adds another metaphor: the gears of industry grinding human life into repetition. Yet even here, the Tramp and the Gamin walk off together, the long way, not the shortcut; suggesting resilience and hope. Between them, Modernism oscillates: fog and clarity, glow and bite, labyrinth and mirror, machine and memory. Meaning is elusive but never absent. It waits in the folds of memory, in the flash of wit, in the shadows of desire, in the detours of the long way, ready to be revealed.

Through memory’s fragments, along the winding road of joy and grace, we taste again the sweetness of love, the timelessness of innocence, and life’s inexhaustible richness.

Graphic: Marcel Proust, Hulton Archive/Getty Images.