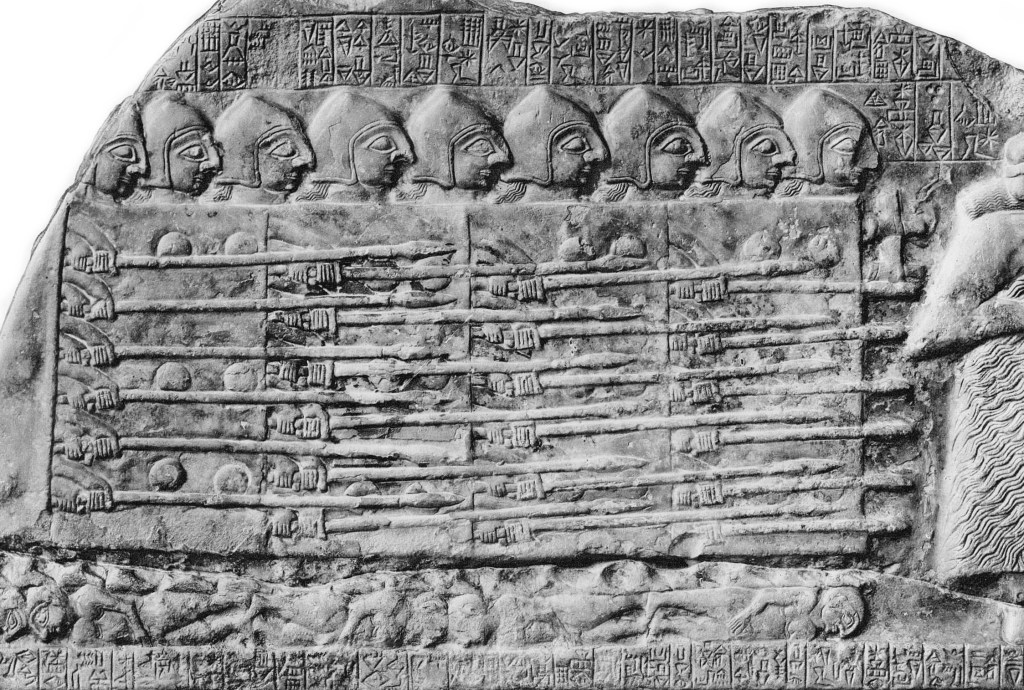

Near the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu, mid-way between present-day Bagdad and Kuwait City, stood a battle marker; the Stele of Vultures, now housed in the Louvre. It commemorates Lagash’s 3rd millennium BC victory over Umma. The stele derives its name from the monument’s carved vultures flying away with the heads of the dead. It also depicts soldiers of Lagash marching in a dense, shield to shield formation, holding spears chest high and horizontal, led by their ruler: Eannatum, who commissioned the stele in 2460 BC. The importance of the stele, though, is that it is the first visual depiction of the use of a phalanx in a battle. It is believed that the phalanx as a military tactic is much older.

The phalanx was more than a combat formation, it was a battlefield philosophy enshrining discipline and courage over strength, unity of the team over the individual. A dense, rectangular wall of men, generally 8 deep stretching across the battlefield to protect against flanking maneuvers. Each man wore heavy armor of leather and bronze: helmet, cuirass, greaves, armed with a spear and a short sword. But the breakthrough that brought the phalanx great renown was the apsis, a round shield invented for the Greek hoplite in the 8th or 7th century BC. With its dual grip, a forearm strap and central handhold, it allowed the infantryman precise control of his shield, helping create an impenetrable barrier of bronze and bone against the oncoming enemy’s spears and swords. It transformed the phalanx from an offensive wall of attack to an added defensive engine of defiance.

The phalanx only succeeded in cohesion. When courage and discipline held, the formation with the apsis as its core defense was practically unbeatable on confined terrain. It overcame the enemy with a seamless, tight mass executing a relentless forward march into the belly of the opposing beast. But it was only as strong as its weakest link. Once discipline faltered and cohesion broke, the formation collapsed, and the opposing army ran it to ground. Victory belonged not to brute force, but to the combined strength of the military unit. Teams won, individuals lost.

From late 8th century BC onward, Greek phalanxes were manned by hoplites: citizen soldiers, generally landowners and farmers. Emerging in Sparta or Argos, possibly imported from Sumeria or born of parallel discovery in Greece, phalanx battles initially were confined, blunt, and deadly affairs. They devolved into fierce pushing masses of brawn, bone, and metal until one side broke. Heavy casualties occurred when the enemy lines broke and soldiers fled Helter skelter in shock and chaos, pursued by the victors for plunder, unless they were restrained by honor.

The phalanx became the standard that destroyed the mighty Persian armies at Marathon and Thermopylae early in the 5th century BC. At Marathon in 490 BC 10,000 Athenians and 1000 Plataeans stretched out their formation to match the breadth of 26,000 Persians, filling the Marathon plain and denying the armies any room for flanking movements.

The Greeks stacked their wings with additional rows of hoplites and thinned them progressively toward the center creating a convex crescent. The Greek wings advance faster than the center generating a pincer movement that collapsed on the Persian center. When the dust settled 192 Athenians and 11 Plataeans were lost while the Persian losses were approximated at 6400.

In the 19th century, Napoleon, possibly improvising on phalanx encircling tactics developed at Marathon, would invert his attacking army with a concave formation consisting of a strong center and weaker wings. His strategy being to split the enemies’ center with strength and attack their divided ranks on the flanks. The tactic worked until Wellington at Waterloo.

At Marathon, unity triumphed with geometric discipline. At Thermopylae the formation bought time and ended with a sacrifice that concluded Persian hubris.

During the second Persian invasion in 480 BC, Darius’s son Xerxes with 120,000-300,000 men attacked a contingent of 7000 Greeks at Thermopylae. The Greeks held back the Persian advance like a cork in a bottle, using a rotating phalanx of roughly 200 men to defend a narrow pass for two days, until betrayal by Ephialtes exposed their flank and they were destroyed in a inescapable Persian barrage of arrows. Greek losses were estimated at 4000 men including Leonidas’ 300 Spartans and 2000-4000 Persians (beginning and ending estimates for manpower strength vary widely).

The Greeks defiant stand at Thermopylae allowed the Greek navy to regroup at Salamis where they won a decisive victory against the Persian navy. A year later the Greeks at Plataea crushed the Persians quest for a Hellenic satrapy.

The Phalanx endured for another century, including use in the Peloponnesian War, where it remained lethal but of limited use. Then came Epaminondas at Leuctra in 371 BC, transforming the phalanx into a machine that erased Sparta’s mighty reputation. Typically, each army’s phalanx strength was concentrated on their right wing so that the strongest part of a force always faced off against the weaker wing of the opposition. What Epaminondas did was say nuts to that.

He reversed the order and created an oblique formation, more triangular than rectangular with his strongest troops on the left wing. His left wing was stacked 50 deep while keeping his center and right wings thin. His 50-deep was aimed directly at Sparta’s best under the command of King Cleombrotus (in those days officers and kings were in the front rows of the phalanx). As the phalanxes began to attack Epaminondas kept his right-wing stationery creating an asymmetrical front. The left wing easily broke through Sparta’s right wing, killing Cleombrotus and collapsing their superior flank. At that point Epaminondas’s wing pivoted inward creating an enveloping arc around the remaining parts of Sparta’s phalanx effectively ending the Spartan myth of invincibility.

Epaminondas tactics shortened battles with fewer casualties. His innovations proved that properly trained and equipped citizen soldiers could defeat professional warriors while instilling a new civic honor through restraint and discipline. His oblique formation allowed landowners and farmers to settle their disputes, usually in a few hours or less, with minimal loss, and return to their farms in time for the harvest. Epaminondas not only brought asymmetrical tactics to the battlefield but shattered claims of superiority by employing the unexpected.

As the Golden Age of Athens and western civilization’s Greek center waned and Roman hegemony rose, the phalanx evolved again. The Greek phalanx gave way to the Roman manipular system, a staggered checkerboard pattern, enabling units to rotate, reinforce, or retreat as needed. It was a needed refinement and improvement to the phalanx, more effectual on open plains and less susceptible to calvary and arrows.

Then came Hannibal to Cannae in 216 BC. During the 2nd Punic War, he upended the war cart of tactics once again and ruthlessly exploited Rome’s refinements.

Hannibal’s improvisations of the phalanx maneuvering tactics, but not the actual formation, showed that he had studied Marathon. Instead of a convex line with strong wings and a weak center he developed a concave line with strong wings and weak center. He allowed the center to fall back, which the Romans unwittingly obliged by surging into Hannibal’s weak center. With the Romans committed Hannibal’s deception encircled them with precision and brutal lethality. The Romans were annihilated on the field losing somewhere between 50,000-70,000 killed and another 10,000 captured. Hannibal lost 6000-8000 men (again estimates vary). Then came the 3rd Punic War.

The phalanx began as a wall of spears and shields, a bulwark of bronze and bone. Its stunning victories echo through history’s scholarly halls and hallowed plains of death and destruction. Yet its Achilles’ heel, vulnerable flanks, precise terrain requirements proved incompatible to horses and gunpowder.

Still its legacy of discipline and unity endure. Born of necessity, refined through rigor, and studied for centuries, the phalanx stands as a testament Aristotle’s enduring insight, slightly abridged but still profound, ‘The whole is greater than the parts.’ And perhaps the Roman’s said it best: ‘E pluribus unum’, ‘out of many, one.’

Source: A War Like No Other by Victor Davis Hanson, 2005. Et al. Graphic: Stele of Vultures.