(Note: This companion essay builds on the previous exploration of Asimov’s moral plot devices, rules that cannot cover all circumstances, focusing on dilemmas with either no good answers or bad answers wrapped in unforgiving laws.)

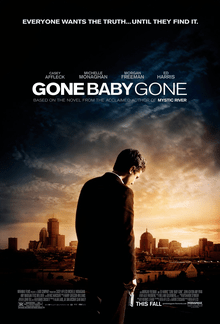

Gone Baby Gone (2007) begins as a textbook crime drama; abduction of a child, but by its final act, it has mutated into something quietly traumatic. What emerges is not a crime thriller, but an unforgiving philosophical crucible of wavering belief systems: a confrontation between legal righteousness and moral intuition. The two protagonists, once aligned, albeit by a fine thread, find themselves, eventually, on opposite ends of a dilemma that law alone cannot resolve. In the end, it is the law that prevails, not because justice is served, but because it is easy, clear, and lacking in emotional reasoning. And in that legal clarity, something is lost, a child loses, and the adults can’t find their way back to a black and white world.

The film asks: who gets to decide for those who can’t decide for themselves? Consent only functions when the decisions it enables are worthy of those they affect.

The film exposes the flaws of blindly adhering to a legal remedy that is incapable of nuance or a purpose-driven outcomes; not for the criminals, but for the victims. It lays bare a system geared towards justice and retribution rather than merciful outcomes for the unprotected victims or even identifying the real victims. It’s not a story about a crime. It’s a story about conscience. And what happens when the rules we write for justice fail to account for the people they’re meant to protect, if at all. A story where it was not humanly possible to write infallible rules and where human experience must be given room to breathe, all against the backdrop of suffocating rules-based correctness.

Moral dilemmas expose the limits of clean and crisp rules, where allowing ambiguity and exceptions to seep into the pages of black and white is strictly forbidden. Where laws and machines give no quarter and the blurry echoing of conscience is allowed no sight nor sound in the halls of justice or those unburdened by empathy and dimensionality. When justice becomes untethered from mercy, even right feels wrong in deed and prayer.

Justice by machine is the definition of law not anchored by human experience but just in human rules. To turn law and punishment over to an artificial intelligence without soul or consciousness is not evil but there is no inherent goodness either. It will be something far worse: A sociopath: not driven by evil, but by an unrelenting fidelity to correctness. A precision divorced from purpose.

In the 2004 movie iRobot, loosely based on Isaac Asimov’s 1950 novel of the same name, incorporating his 3 Laws of Robotics, a robot saves detective Del Spooner (Will Smith) over a 12-year-old girl, both of whom were in a submerged car, moments from drowning. The robot could only save one and picked Smith because of probabilities of who was likely to survive. A twist on the Trolley Problem where there are no good choices. There was no consideration of future outcomes; was the girl humanity’s savior or more simplistic, was a young girl’s potential worth more, or less, than a known adult.

A machine decides with cold calculus of the present, a utilitarian decision based on known survival odds, not social biases, latent potential, or historical trajectories. Hindsight is 20-20, decision making without considering the unknowns is tragedy.

The robot lacked moral imagination, the capacity to entertain not just the likely, but the meaningful. An AI embedded with philosophical and narrative reasoning may ameliorate an outcome. It may recognize a preservation bias towards potential rather than just what is. Maybe AI could be programmed to weigh moral priors, procedurally more than mere probability but likely less than the full impact of human potential and purpose.

Or beyond a present full of knowns into the future of unknowns for a moral reckoning of one’s past.

In the 2024 Clint Eastwood directed suspenseful drama, Juro No. 2, Justin Kemp (Nicholas Hoult) is selected to serve on a jury for a murder trial, that he soon realizes is his about his past. Justin isn’t on trial for this murder, but maybe he should be. It’s a plot about individual responsibility and moral judgment. The courtroom becomes a crucible not of justice, but of conscience. He must decide whether to reveal the truth and risk everything, or stay silent and let the system play out, allowing himself to walk free and clear of a legal tragedy but not his guilt.

Juro No. 2 is the inverse of iRobot. An upside-down moral dilemma that challenges rule-based ethics. In I, Robot, the robot saves Will Smith’s character based on survival probabilities. Rules provide a path forward but in Juro No. 2 the protagonist is in a trap where no rules will save him. Logic offers no escape; only moral courage can break him free from the chains of guilt even though they bind him to the shackles that rules demand. Justin must seek and confront his soul, something a machine can never do, to make the right choice.

When morality and legality diverge, when choice runs into the murky clouds of grey against the black and white of rules and code, law and machines will take the easy way out. And possibly the wrong way.

Thoreau in Civil Disobedience says, “Law never made men a whit more just; and… the only obligation which I have a right to assume is to do at any time what I think right,” and Thomas Jefferson furthers that with the consent of the governed needs to be re-examined when wrongs exceed rights. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is the creed of the individual giving consent to be governed by a greater societal power but only when the government honors the rights of man treads softly on the rules.

Government rules, a means to an end, derived from the consent of the governed, after all, are abstractions made real through human decisions. If the state can do what the individual cannot, remove a child, wage war, suspend rights, then it must answer to something greater than itself: a moral compass not calibrated by convenience or precedent, but by justice, compassion, and human dignity.

Society often mistakes legality for morality because it offers clarity. Laws are neat, mostly. What happens when the rules run counter to common sense? Morals are messy and confusing. Yet it’s in that messiness, the uncomfortable dissonance between what’s allowed and what’s right, that our real journey towards enlightenment begins.

And AI and machines can erect signposts but never construct the destination.

A human acknowledgement of a soul’s existence and what that means.

Graphic: Gone Baby Gone Movie Poster. Miramax Films.