In Shel Silverstein’s poem “Falling Up,” a child trips on his shoelace and soars skyward instead of tumbling down. A delightful inversion of reality, a child’s imagination conjuring tomorrow’s focus. In the world of mathematics and physics, a similar inversion has captivated minds for decades: can you design an object that always falls the same way, always sunny side up, no matter how it starts, like a cat landing on all fours.

In the realm of numbers and materials this is the problem of monostability: creating a shape that, when placed in any orientation, will always return to a single, stable resting position. It’s a deceptively simple question with grudgingly difficult solutions. And it has at least two very different answers.

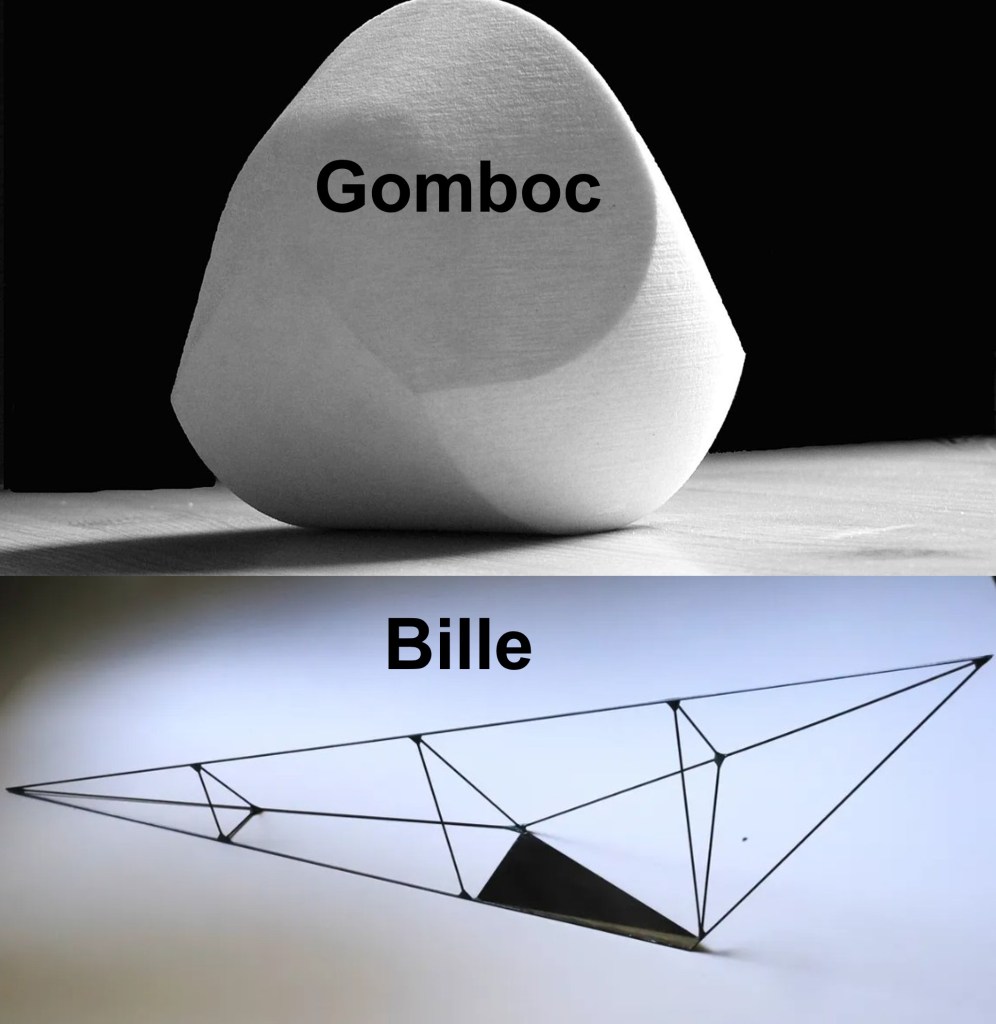

The first answer to the cat landing on all fours came in 2006 with the discovery of the Gömböc, a smooth, convex, homogeneous shape that rights itself without any differential weighting or moving parts. Invented by Hungarians Gábor Domokos and Péter Várkonyi, the Gömböc, meaning “little sphere or roundy” in Hungarian, has only one stable and one unstable equilibrium point. No matter how you place it, it will wobble and roll until it settles in its preferred orientation.

The Gömböc is a triumph of pure geometry. It solves the monostability problem using only shape, no tricks, no hidden weights but some serious math. It’s been compared to a mathematical cat: always landing on its feet, a design with a natural convergence toward the domed asymmetry of tortoise shells, whose shapes nature may have unconsciously optimized for self-righting.

Although uses for Gömböc are still being explored, some have developed designs for passive orientation systems, and the name has been co-opted for a company that is building self-correcting cloud infrastructure.

The second answer came recently in June of this year, when Gergő Almádi, Robert Dawson, and Gábor Domokos, of Gomboc fame, constructed a monostable tetrahedron, a four-faced scalene or irregular polyhedron that always lands on the same face which they named Bille: “to tip or to tilt” in Hungarian. A solution to a decades-old conjecture by John Conway, a Princeton polymath professor, with a talent for finding tangible solutions to abstract problems.

In this case, unlike the geometric solution of the Gömböc, geometry enables self-righting only when paired with carefully engineered mass distribution: a lightweight carbon-fiber frame and a dense tungsten-carbide core, precisely positioned to shift the center of gravity into a narrow “loading zone.” It’s a hybrid of form and force, where the shape permits monostability, but the mass forces the issue.

Unlike the Gömböc, which might inspire real-world designs, the monostable tetrahedron is too fragile, too constrained, and too dependent on ideal conditions to be practical. It’s a mathematical curiosity, not an engineering breakthrough. But like numerous mathematical solutions, practicality may occupy some interesting spaces in the future because landing on your feet is a useful function in many areas of commerce and science.

In space exploration lunar landers have recently had a bad, and expensive habit of falling over. In marine safety, users of escape pods and lifeboats prefer them to remain upright and watertight. Come to think most occupants of any watercraft prefer to remain upright and dry. Robots and drones benefit from shapes that naturally return them to a functional position without motors or sensors.

In the end, both the Gömböc and the weighted tetrahedron are about their inevitable position and stability. They are objects that always know where they stand. One does it with elegance; the other with abstraction and compromise. One is a cat. The other is a clever box of lead and air.

And maybe that’s the real lesson of “falling up”: that sometimes, the most interesting ideas aren’t the ones that solve problems, but the ones that reframe the question, and quietly remind us that some problems, left alone, reveal their own solutions.

As Calvin Coolidge once observed, “If you see ten troubles coming down the road, you can be sure that nine will run into the ditch before they reach you.” Meaning he didn’t need to attack and solve 10 problems, just the persistent one. The Gömböc and Bille didn’t wait for the problem to develop, they honored the ditch. Their designs never left the ditch. The problem never materialized in the first place.

Source: Mon-monstatic Bodies by Varkonyi and Domokos, Springer Science, 2006. Bulilding a Monostable Tetrahedron by Almadi et al, arXiv, 2025.