“One must either be one of a thousand or all alone,” declared Edouard Manet (1832-1883). Critics and even some among the Impressionist circle believed Manet lacked the courage to be truly alone, both with his art and his essence. And they were half right. He was an extrovert, a social creature drawn to the vivacious pulse of Parisian life, its salons, cafes, and couture. He wanted to belong.

Through his art he sought recognition. He wanted not necessarily respect, but rather something simpler: acceptance. Yet they misunderstood his paintings. He was alone. His canvass spoke volumes to him, but the critics saw only muted, unfulfilled talent. Paintings adrift in a stylistic wilderness. The arbitrators of French taste, the Salon jury, repeatedly rejected him. In 1875 upon viewing The Laundress, one jury exploded: “That’s enough. We have given M. Manet ten years to amend himself. He hasn’t done so. On the contrary, he is sinking deeper.”

Manet longed for approval, and he could deliver what the critics wanted, but the moment he picked up his brush something else took over. He painted what he saw, but never fully controlled the production. His canvases resisted labels. A modern Romantic, a Naturalist with a Realist bent, urban but Impressionistic. A cypher to the critics but true to himself.

Like his friend Degas, he painted contemporary city life. The country landscapes of Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro couldn’t hold him. The color and light of the Impressionists intrigued him briefly, but stark lighting and unconventional perspective held him fast. He used broad quick solid brush strokes and flat, cutout forms.

Manet’s style was rebellion. The critics sensed it, and hated it, but they never understood it. He couldn’t digest academic art, so revered by the Salon. His mutiny was expressed through paint, not polemic. His only verbal defense was a cryptic comment that “anything containing the spark of humanity, containing the spirit of the age, is interesting.”

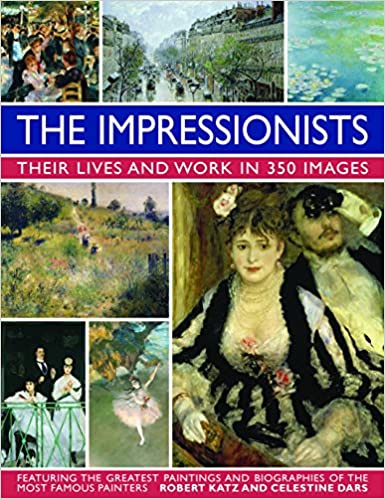

Nowhere is humanity, the spirit of the age, more hauntingly distilled than his masterpiece, his Chef-d’oeuvre: Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets. Dressed in black, her face half in shadow, Morisot peers questioningly at the viewer, asking what comes next. Manet paints what he sees. And he sees the mystery of femininity. Her green eyes painted black providing an opacity to her gaze, deepening the ambiguity: a comicality behind an expression of curiosity.

Critic Paul Valery wrote, “I do not rank anything in Manet’s work higher than a certain portrait of Berthe Morisot dated 1872.” He likened it to Vermeer, but with more spontaneity that makes this painting forever fresh. It is a timeless, loving portrait that transcends style.

Source: The World of Manet: 1832-1883 by Pierre Schneider, 1968. Graphic: Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets by Edouard Manet, 1872. Musee d’Orsay, Paris. Public Domain.