One Flew Over the Cockoo’s Nest

By Ken Kesey

Penguin Group

Copyright: © 2012

Original Copyright: © 1962

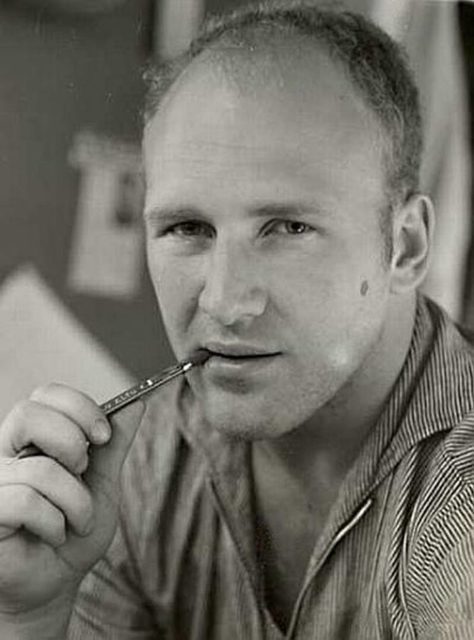

Kesey Biography:

“Since we don’t know where we’re going, we have to stick together in case someone gets there.” Kesey

Ken Kesey, who died at the age of sixty-six in 2001, was a novelist, hippie, and beatnik, tuning into the counterculture movement of the sixties that renounced materialism, institutions, and the middle-class, while embracing LSD, free-sex, and carrots. Kesey, I believe, just embraced LSD, grass, and laughs.

After finishing college at the University of Oregon–go Ducks–he moved to California and enrolled in Stanford–go Tree??–to study creative writing from 1958 to 1961 while simultaneously settling into the counterculture lifestyle gripping the area and the nation.

In 1959 he volunteered for the CIA’s LSD mind experiments being run under the code name MKUltra. These experiments were conducted at a VA hospital in Menlo Park, just northwest of Stanford. At the same time in 1959 he accepted a position as an attendant in the hospital’s psych ward, working there while tripping on LSD. He began writing One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in 1959 or 60 (various sources give different dates). In 1962 Kesey published his masterpiece. The rest is history.

Later, in 1964 Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters, a group he and others formed in the late fifties, bought an old school bus, repainted it in the pop art and comic book style of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein respectively, and took off to survey and crash the Beatnik scene in New York City. While on the road to New York they handed out LSD in various forms, it wasn’t illegal until 1966, and held street party theater for the locals. The whole experience was recorded with microphones and cameras along with several books being written afterwards about the experience.

After returning to California in 1965 Kesey was arrested for marijuana possession. Fearing prison, he faked his suicide which didn’t really fool the police and escaped to Mexico. A few months later in 1966 he was captured and sent to an honor prison camp in Redwood City, California for six months where he cleared brush and kept a diary of his experience later publishing it as Kesey’s Jail Journal: Cut the M*********** Loose.

Upon release from prison, he gave up the bohemian lifestyle, returned to Oregon, and settled down to the life of a respectable middle-aged citizen with a little acid and weed still making recreational appearances.

Defending his drug use he made the point, in an interview with Charley Rose in 1992, that doing drugs was a personal decision and if your neighbor incurred no harm, then no one need be concerned. A thoroughly libertarian position not terribly different than William Buckley’s view on pot. He also denied being a mindless drug addict stating in an interview with Terry Gross, “I’ve always been a reliable, straight-up-the-middle-of-the-road citizen that just happens to be an acidhead.”

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest:

The story’s narrator, Chief Bromden, a 6’6″ tall member of a Columbia River Indian tribe, is a schizophrenic patient in an Oregon psychiatric hospital, passing himself off as a deaf, mute with an agreeable disposition. Bromden forms a bond of friendship with Randle McMurphy, a new psych patient who, rather than put in a few months in at a prison work farm, convinces his jailers that he is insane so he can get transferred to a no work sanitorium with better meals. McMurphy initially finds his situation much improved and installs himself as head crazy but quickly butts heads with Nurse Ratched the chief administrator for his floor. Nurse Ratched is a humorless soul sucking battle axe who quickly realizes that she is in a clash of Titans and wits with McMurphy where the winner takes all. As in Macbeth only one king, or Queen, shall live or as Shakespeare states, “if the assassination / Could trammel up the consequence”. In today’s vernacular, the Machiavellian “when you set out to kill the king, you must kill him” and damn the repercussions is more succinct.

Literary Criticism:

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is one of the best American novels written in the latter half of the twentieth century easily standing with Steinbeck’s East of Eden and Of Mice and Men, Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, and Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. Except for Hemingway’s novella they all explore good and evil within the context of human nature and its effect on one’s soul. Kesey’s book pokes and prods the reader with almost farcical battles of weak minds against strong minds. Wills of strength versus the will of the state. Occasional good against consistent evil.

Every literary device and human character flaw known has been applied to this novel, simile, metaphor, personification, action, protagonist, antagonist, conflict, allusion, imagery, climax, male chauvinism, misogynism, sexuality, sexual repression, fear, hate, violence, intimidation, dominance; it is all here, a masterpiece of storytelling that maybe only Dickens was capable of duplicating.

In Aristophanes’ play The Birds he invented the term “cloud cuckoo land” as the name for his bird utopia but in reality, it was the home for the absurd. Whether Kesey intended to imitate Aristophanes social criticism and sarcasm inherent in The Birds is not known but they both found their subject matter bizarre and ridiculous.

Mental Health and the Cuckoo’s Nest:

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the book, the play, the movie, likely accelerated the deinstitutionalization of mental patients in the U.S. and the world. It was a process that had already begun in the mid-fifties with the introduction of the antipsychotic drug, chlorpromazine, allowing mental illness to be treated outside of a hospital setting. In the sixties and seventies President Kennedy and California Governor Reagan were champions of providing mental health services without walls. In hindsight it should have been easily anticipated the inevitable negative consequences of such policies. Homelessness and incarceration, rampant use of illicit drugs and crime, the general breakdown of societal norms when the mentally ill were allowed to take charge of their own care without supervision. Assuming logical outcomes from illogical inputs is well–illogical.

In Virgil’s Aeneid he wrote, “facilis descensus Averno (the descent to hell is easy)” or as Samuel Johnson updated the proverb by stating, “…hell is paved with good intentions”. Today we just say the “Road to hell is paved with good intentions” and hell is a dystopian wasteland.

Kesey Bibliography:

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. 1962

- Sometimes a Great Notion. 1964

- Kesey’s Garage Sale. 1973

- Demon Box. 1986

- Caverns. 1989 (with his Oregon creative writing class students)

- The Further Inquiry. 1990

- Little Tricker the Squirrel Meets Big Double the Bear. 1990 (Illustrated by Barry Moser)

- The Sea Lion: A Story of the Sea Cliff People. 1991 (Illustrated by Neil Waldman)

- Sailor Song. 1992

- Last Go Around. A Real Western. 1994. (with Ken Babbs)

- Twister: A Ritual Reality in Three-Quarters Plus Overtime if Necessary (Play). 1994 (with Ken Babbs)

- Twister: A Musical Catastrophe. (Video). 2000 (with Ken Babbs)

- Kesey’s Jail Journal: Cut the M*********** Loose. 2003

References and Readings:

- Ken Kesey On Misconceptions Of Counterculture. By Terry Gross. NPR-Fresh Air. 1987

- Ken Kesey Interview. with Charley Rose. YouTube. 1992

- Ken Kesey. By Lee Daniel Crocker. Wikipedia. 2001 (Latest Update 2023)

- One Flew Over Cuckoo’s Nest (Movie). By Koyaanis Qatsi. 2001 (Latest Update 2023)

- Beat Generation. Uncredited. Wikipedia. 2002 (Latest Update 2023)

- MKUltra. By The Anome. Wikipedia. 2002 (Latest Update 2023)

- Merry Pranksters. By Ihcoyc. Wikipedia. 2003 (Lastest Update 2023)

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. By Abryn. Wikipedia. 2005 (Latest Update 2023)

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Play). By Michael Billington. The Guardian. 2006

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Play). By Ganfon etal. Wikipedia. 2006 (Latest Update 2023)

- Still Cuckoo After All These Years. By James Wolcott. Vanity Fair. 2011

- Conversations with Ken Kesey. By Scott F. Parker. University Press of Mississippi. 2014

- How Ken Kesey’s Life Influenced “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest”. By Alex Cichy. HubPages. 2014

- The Conservative Case for Legalizing Marijuana. By Lily Rothman. Time. 2015

- Ken Kesey, Writer of “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest”, Faked His Death to Avoid Getting Arrested for Marijuana Posession. By Brad Smithfield. The Vintage News. 2017

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. By Andrew Pepper. Britannica. 2017

- An Analysis Of “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest“. By Elisabeth Murphy. Odyssey. 2017

- MK-Ultra. By History.com Editors. History.com. 2018

- Ken Kesey. Uncredited. Biography. 2020

- Discuss the Theme of Mental Illness in Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Uncredited. Literopedia. 2023

- Ken Kesey. Uncredited. Britannica. 2023

- Literary Criticism: “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” by Ken Kesey. BrightHub. No date

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Uncredited. Literary Devices. No date

- Ken Kesey, Novelist and Hero of 1960s Counterculture. Uncredited. ThoughtCo. No date

- Ken Kesey Quotes. Uncredidted AZQuotes. No date

FootnoteA: Photo of Ken Kesey. Maybe copyrighted. Copyright is ambiguous. Possilby Vintage News 2017

FootnoteB: Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters Bus

FootnoteC: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest Starring Jack Nicholson and Louise Fletcher. Amazon Picture