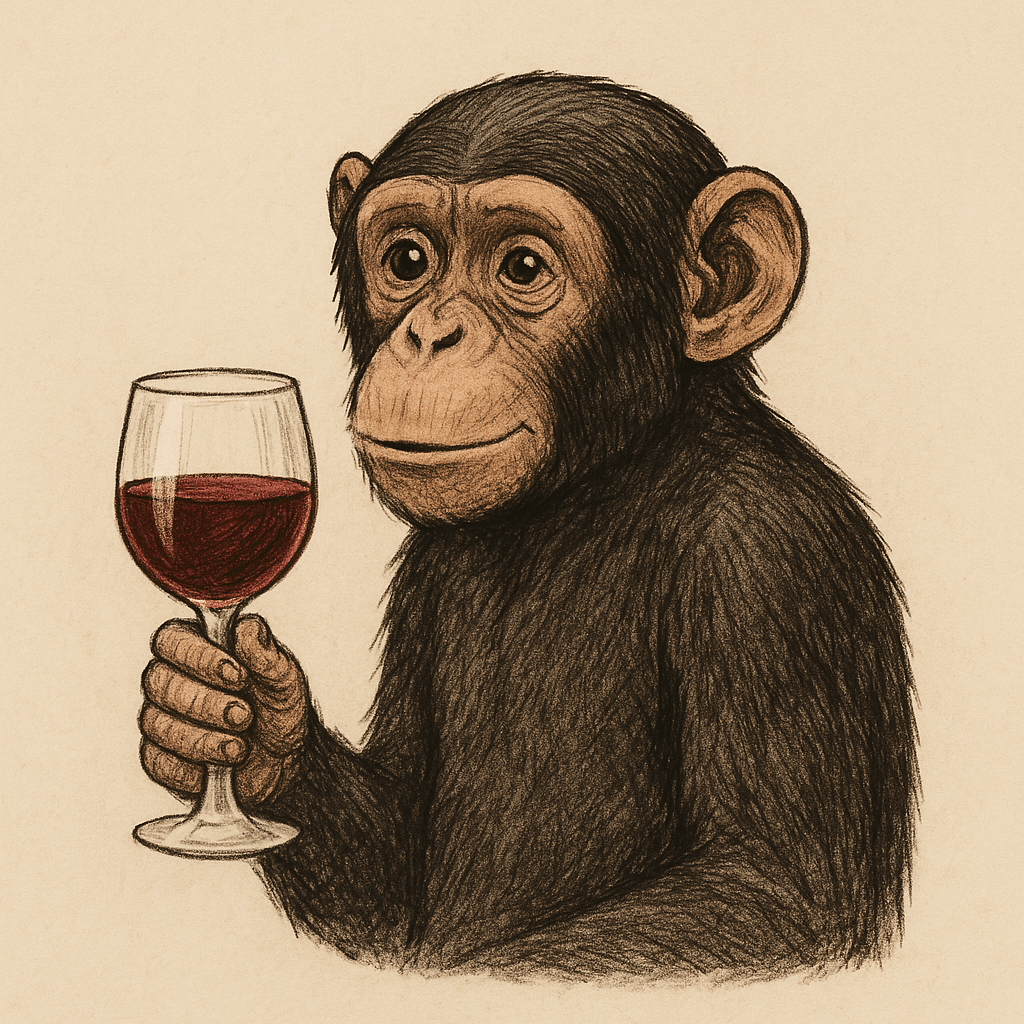

In 2004, biologist Robert Dudley of UC Berkeley proposed the Drunken Monkey Hypothesis, a theory suggesting that our attraction to alcohol is not a cultural accident but an evolutionary inheritance. According to Dudley, our primate ancestors evolved a taste for ethanol (grain alcohol) because it signaled ripe, energy-rich, fermenting fruit, a valuable resource in dense tropical forests. Those who could tolerate small amounts of naturally occurring ethanol had a foraging advantage, and thus a caloric advantage. Over time, this preference was passed down the evolutionary tree to us.

But alcohol’s effects have always been double-edged: mildly advantageous in small doses, dangerous in excess. What changed wasn’t the molecule, it was our ability to concentrate, store, and culturally amplify its effects. Good times, bad times…

Dudley argues that this trait was “natural and adaptive,” but only because we didn’t die from it as easily as other species. Ethanol is a toxin, and its effects, loss of inhibition, impaired judgment, and aggression, are as ancient as they are dangerous. What may have once helped a shy, dorky monkey approach a mate or summon the courage to defend his troop with uncharacteristic boldness now fuels everything from awkward first dates, daring athletic feats, bar fights, and the kind of stunts or mindless elocutions no sober mind would attempt.

Interestingly, alcohol affects most animals differently. Some life forms can handle large concentrations of ethanol without impairment, such as Oriental hornets, which are just naturally nasty, no chemical enhancements needed, and yeasts, which produce alcohol from sugars. Others, like elephants, become particularly belligerent when consuming fermented fruit. Bears have been known to steal beer from campsites, party hard, and pass out. A 2022 study of black-handed spider monkeys in Panama found that they actively seek out and consume fermented fruit with ethanol levels of 1–2%. But for most animals, plants, and bacteria, alcohol is toxic and often lethal.

Roughly 100 million years ago in the Cretaceous, flowering plants evolved to produce sugar-rich fruits, nectars, and saps, highly prized by primates, fruit bats, birds, and microbes. Yeasts evolved to ferment these sugars into ethanol as a defensive strategy: by converting sugars into alcohol, they created a chemical wasteland that discouraged other organisms from sharing in the feast.

Fermented fruits can contain 10–400% more calories than their fresh counterparts. Plums (used in Slivovitz brandy) show some of the highest increases. For grapes, fermentation can boost calorie content by 20–30%, depending on original sugar levels. These sugar levels are influenced by climate, warm, dry growing seasons with abundant sun and little rainfall produce sweeter grapes, which in turn yield more potent wines. This is one reason why Mediterranean regions have long been ideal for viticulture and winemaking, from ancient Phoenicia to modern-day Tuscany, Rioja, and Napa.

The story of alcohol is as ancient as civilization itself. The earliest known fermented beverage dates to 7000 BC in Jiahu, China, a mixture of rice, honey, and fruit. True grape wine appears around 6000 BC in the Caucasus region (modern-day Georgia), where post-glacial soils proved ideal for vine cultivation. Chemical residues in Egyptian burial urns and Canaanite amphorae prove that fermentation stayed with civilization as time marched on.

Yet for all its sacred and secular symbolism, Jesus turning water into wine, wine sanctifying Jewish weddings, or simply easing the awkwardness of a first date, alcohol has always walked a fine line between celebration and bedlam. It is a substance that amplifies human behavior, for better or worse. Professor Dudley argues that our attraction to the alcohol buzz is evolutionary: first as a reward for seeking out high-calorie fruit and modulating fear in risky situations, but it eventually became a dopamine high that developed as an end in itself.

Source: The Drunken Monkey by Robert Dudley, 2014.