“I feel the need of attaining the maximum of intensity with the minimum of means. It is this which has led me to give my painting a character of even greater bareness.” Joan Miro.

Joan Miró (zhwahn mee-ROH, 1893–1983), a Catalan artist, began his career exploring Expressionism and Cubism before rejecting the rational world, which he found suffocating possibly depressing. He turned inward, merging an abstract dreamworld with Surrealism, ultimately evolving into a minimalist, conveying deep meaning through sparse, naïve brushstrokes and colors.

Symbolism became his hallmark; for Miró, the image was secondary to the message which was always open to interpretation. Initially inspired by Van Gogh and Cézanne, he later grew enamored with Picasso and Dalí, but it was Sigmund Freud who awakened his subconscious, plunging him into the mysteries of dreams and hallucinations. In pursuit of these visions, Miró intentionally induced states of hunger and exhaustion, risking madness to capture the fleeting essence of his dreamscapes. His dreams produced a primitive, childlike, whimsical innocence, with no explicit instructions for interpretation.

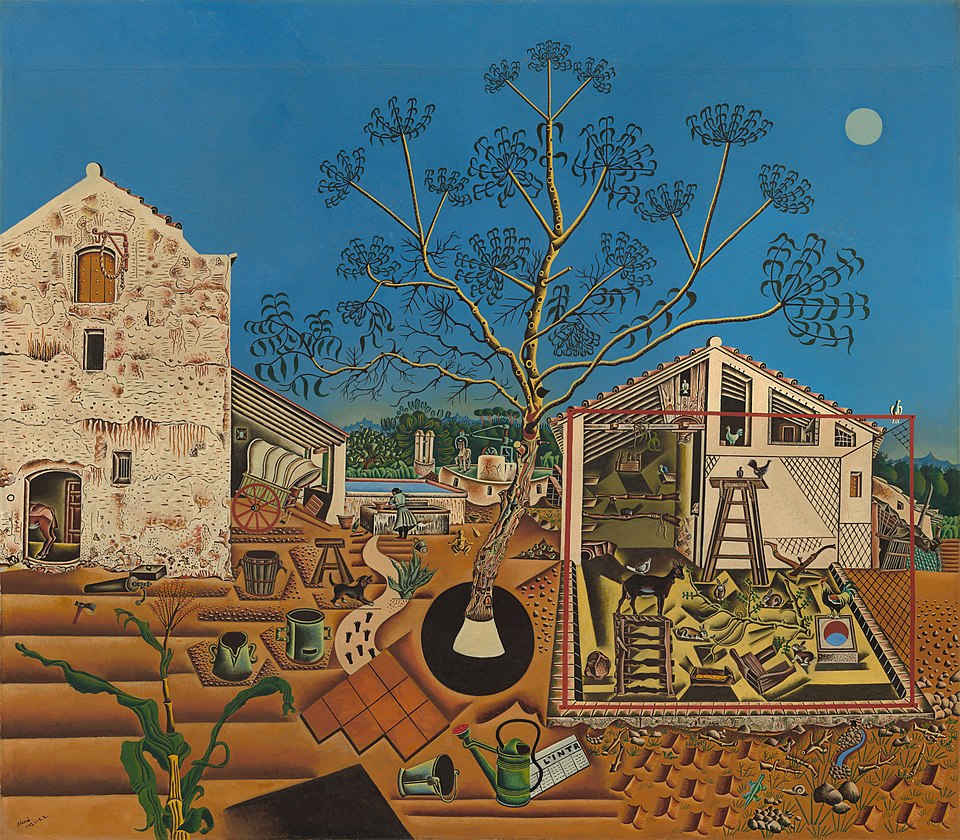

Miró’s early masterpiece, The Farm (1921–22), serves as a biographical snapshot of his life at 29, capturing the essence of his Spanish countryside upbringing and young adult life. This highly detailed precursor to his later Cubist and abstract works was purchased by Ernest Hemingway for 5,000 francs as gift to his wife.

By 2024, Miró’s works continue to command prices that place him among the top 25 most valuable artists worldwide. His Peinture (Étoile Bleue), or Painting (Blue Star), one of his best-known dreamscapes, sold for £23.6 million at a London Sotheby’s auction in 2012, equivalent to $37 million at the time, or approximately $31.5 million in today’s dollars.

Source: Miró by Gaston Diehl, 1979. Graphic: The Farm (1921–1922), National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (Public Domain)