What should you pay for a bottle of wine? Quality, vintage, geographic region, and reputation of the vineyard all influence pricing. Every producer price their wines as high as they believe the market will bear and frequently higher, the same as every other type of business in the world.

Fortunately for the wine drinkers there are about 65,000 wineries in the world producing around thirty-five billion bottles yearly translating into a whole lot of competition to help keep some good wines affordable.

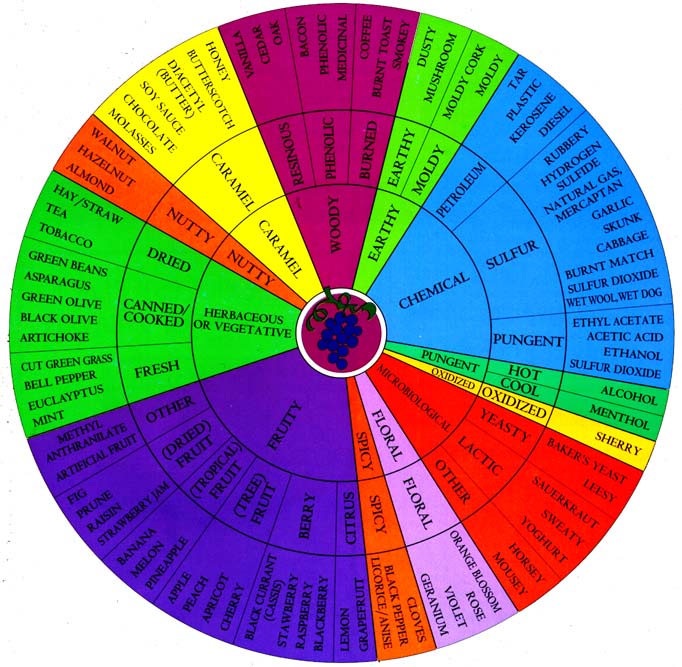

Pricing deals first and foremost with the quality of the wine. Is it any good? Are the components of the wine in balance with each other or do the tannins override the acidity and alcohol? Are the flavors and aromas intense, strong, and bold or weak and faint? Are the flavors and aromas clear and focused or imprecise and expressionless? How complex is wine? Are there multiple layers and nuances? Does the wine exhibit typicity? A great wine will proudly announce its sense of place or its terroir. (Terroir is easier to define for old world wines than it is for new world products.) How’s the finish? Does the taste linger in your mouth after your swallow? An exceptional wine will have a lasting finish.

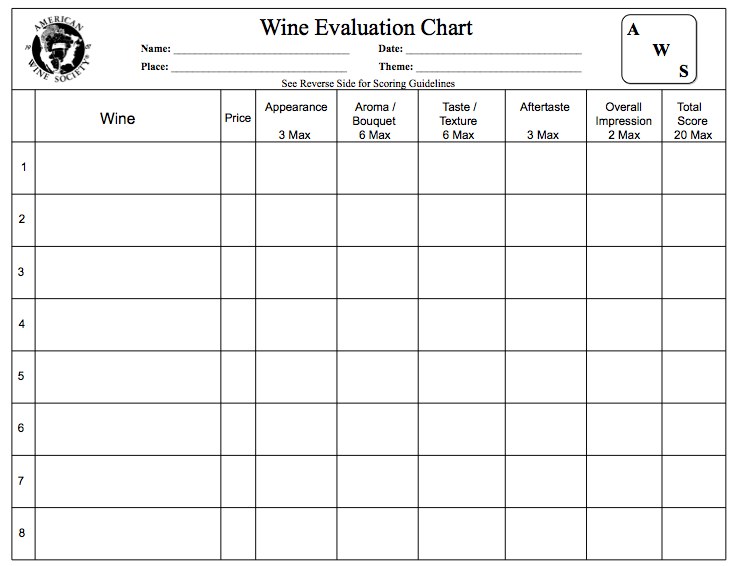

These six factors are used to gauge the quality of the wine and if you wish to go there, its rating. As I discussed in a previous post, a wine’s rating is a subjective affair. Some find it unnecessary. I find it essential. I find it crucial to know a wine’s rating if I’m going to choose a good wine at a fair price. Without ratings get used to drinking bad wines. There are a few different rating systems: a 100-point scale, a 20-point scale, a 5-point scale, a verbal scale, and others. I use the 100-point scale developed by Robert Parker, but I find myself using Vivino’s 5-point or 5-star system more lately. Most wines go unrated. Wines that are rated professionally usually only have one individual rating, and if you’re lucky sometimes up to five or six which you can average for a more realistic score. Wine’s rated by Vivino’s system have tens to hundreds of individual ratings which tend to smooth out the anomalous, spurious ratings inherent to all rating systems.

Secondly, the vintage of the wine has a significant impact on the price of wine. Some high-quality wines such as Bordeaux and cabernet sauvignon can last for one or two decades, even longer if stored properly. 5-10 years after a wine’s harvest date a bottle can appreciate 200-400% from its original selling price or more but be aware that most wines, red and white alike, do not age well and you may end up paying significant money for a bottle of vinegar.

Other factors such as geographic location and vineyard reputation are fluff to what you really care about, a good tasting wine. Chateau Lafite Rothschild or Sine Qua Non produce some great wines but they are way beyond the means of people without mid-six figure incomes.

Apologies for the long intro to the question: what should you pay for a bottle of wine or for purposes of this post, what should you pay for a bottle of outstanding to exceptional, 90–100-point, red wine? I started with 90-point because it is difficult to find professionally rated wines in the public domain lower than that number. The discussion is also limited to reds because I know almost nothing about white or rose wines.

To begin to answer the above question I gathered pricing, vintage, and rating data for almost sixteen hundred different red wines rated at or above 90-points. The wines are sourced from thirteen countries and every continent, except Antartica of course, with the results skewed towards the nine large producing areas listed below:

- Argentina

- Australia

- Chile

- France

- Italy

- Portugal

- South Africa

- Spain

- U.S.

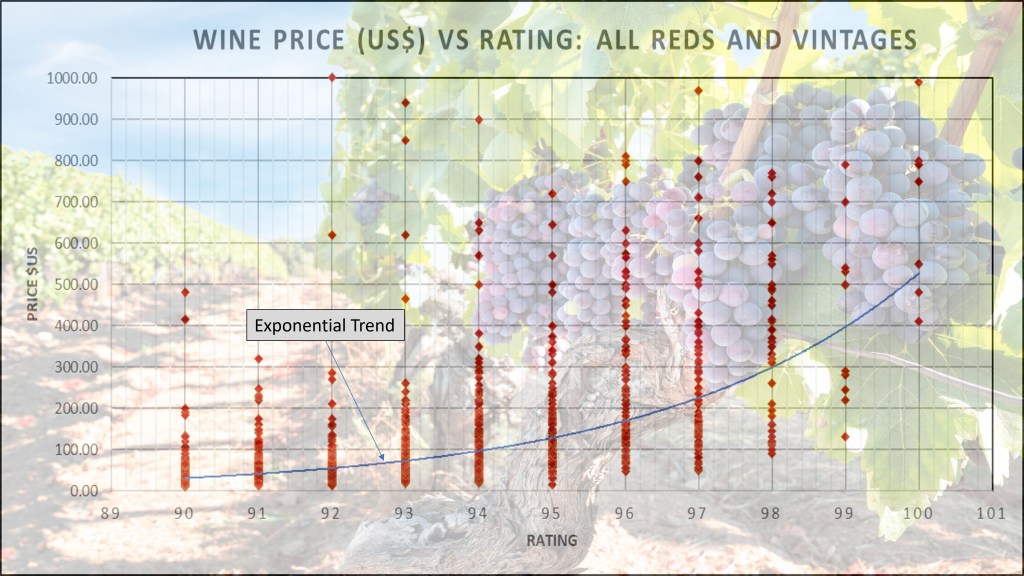

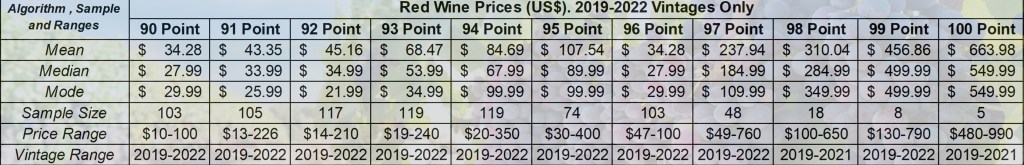

The data were sorted into individual bins by rating and plotted in graphical form as shown above right. The y-axis scale is in dollars and the x-axis is the rating. The y-axis is terminated at $1000 for ease of visualization but there are a handful of wines more expensive than this. The sixteen hundred wines have vintages from 1984-2022. There are very few 2023 reds currently on the market, so they have been excluded. Even though there is a significant amount of scatter in the pricing versus individual rating there is discernable increasing trend in price by higher rating. The trend line shown in blue increasing exponentially from left to right, intersects a 90-point red around $30 and the 100-point at $500 plus.

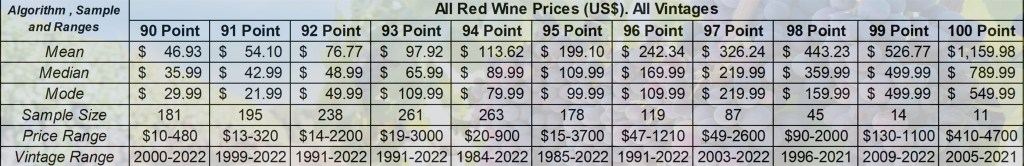

Below is a chart of the data highlighting the calculated mean (average), median (middle value), and mode (most frequent) wine prices by rating for all red wines and vintages in the data set. The median values are the most useful for comparison shopping purposes and I would suggest that this should be the highest price or ceiling one should pay for any given rated wine. Anything above that and you are just purchasing the shiny coat of paint that adds nothing to the quality of wine. When buying wine by rating the lowest price is the most economically sensical purchase to make. I will expand on that piece of advice below.

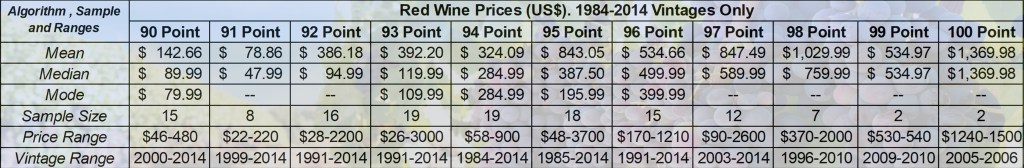

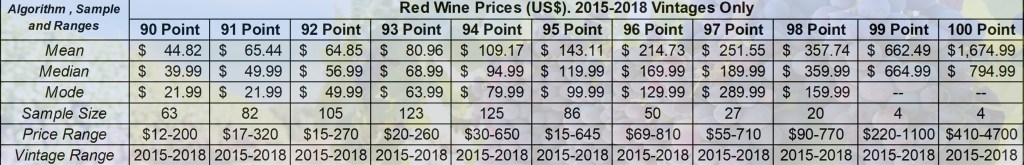

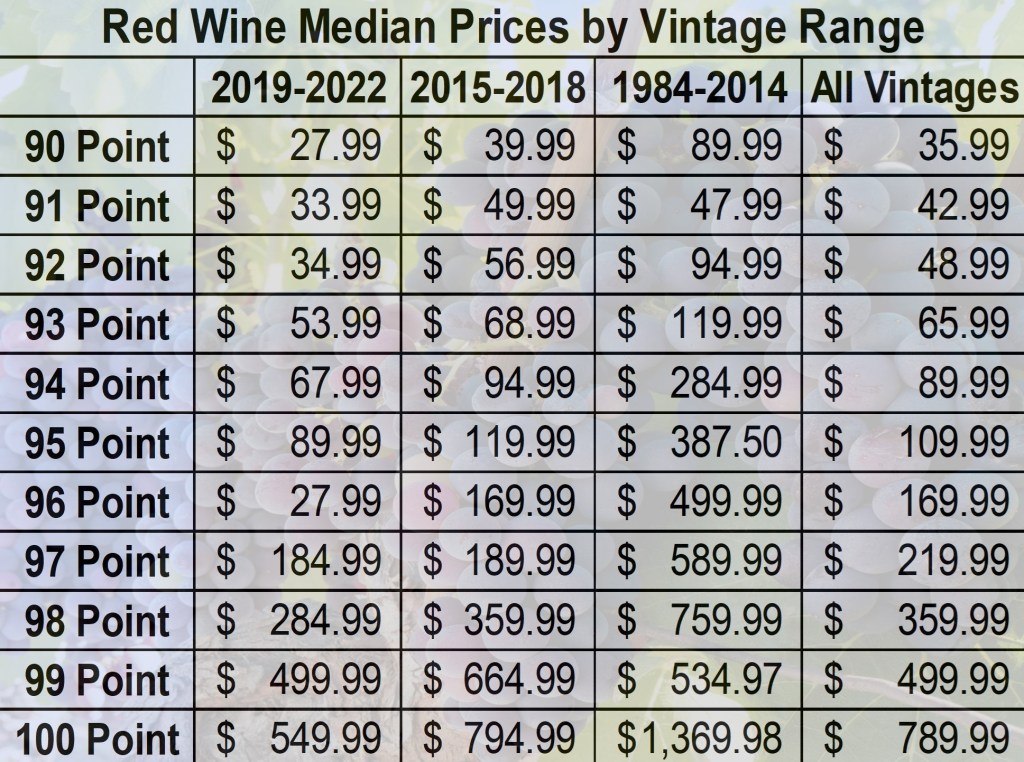

The three charts below are the same format as the one above but confined to bracketed vintages from 1984-2014, 2015-18, and 2019-2022. As one would expect and as stated earlier, aged or older wines are more expensive than their more recent counterparts.

The chart to the left summarizes the median price for the ratings and vintages shown above. Wines increase in price by rating and vintage. Recent wines with a lower rating are cheaper than older wines with higher ratings. Hopefully by taking rating and vintage into account a complicated foray into wine buying will become simple and easily actionable. Keep in mind that the median price should be the highest price paid for any rating and vintage.

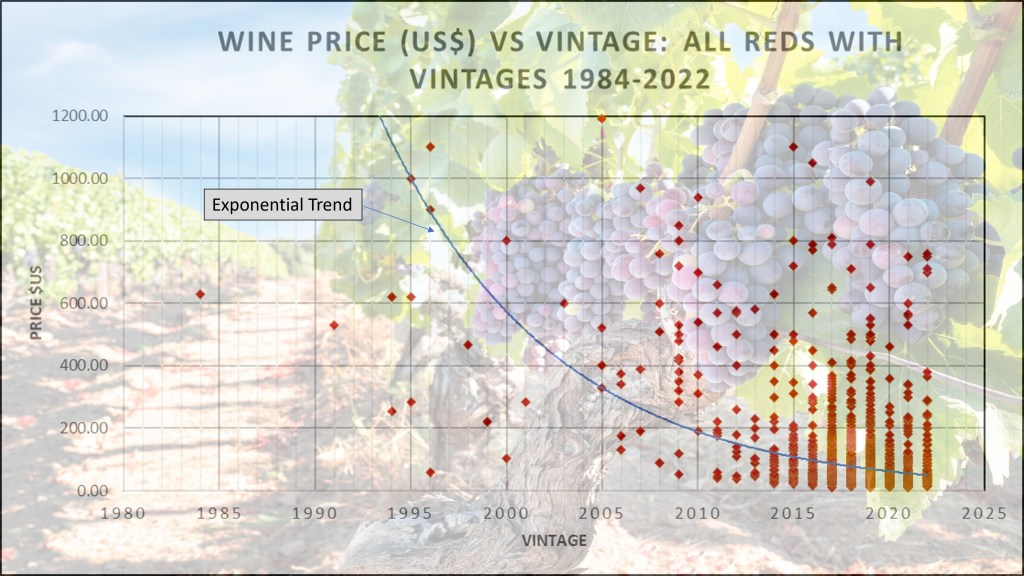

The graph below shows wine prices by vintage. Price is on the y-axis and vintage is on the x-axis. Again, the y-axis is terminated at a lower price than the actual range just to keep visual aspects of the graph manageable. Like ratings the fitted curve trend to price versus vintage is exponential. Older wines cost more, a lot more than recent wines regardless of rating.

In a true to grifter life tale, The Billionaire’s Vinegar: The Mystery of the Worlds’s Most Expensive Bottle of Wine, by Benjamin Wallace details how expensive an old wine can get. Wallace describes how Hardy Rodenstock, allegedly discovered in France a stash of unopened 1787 Chateau Lafite Bordeaux supposedly purchased by Thomas Jefferson while living in Paris after the American Revolution. Rodenstock auctioned a bottle, at Christies, for the tidy sum of $156,000, or $157,000 depending on source, in 1985 to Malcomb Forbes via his son Christopher. In 2023 dollars that would come to $433,740. Rodenstock sold four more bottles to Bill Koch for $400,000 in 1987 or $1,074,378 in 2023 dollars. Old wines can be expensive, and the FBI says they were not only expensive they were also fake. I believe the Feds are still looking for Mr. Rodenstock.

Where do the least and most expensive wines come from? The charts below lists 9 of 11 top wine producing countries in the world and the median price of their wines, as they are priced in the U.S. The yellow highlight is the sorted column. China and Germany are number five and ten in wine production respectively, but little price and rating information is available for comparison purposes, as such they are omitted. Argentina ranks first with the most affordable wines across all outstanding to exceptional rankings. The U.S., mainly California, has the dubious distinction of having the most expensive wines across the 90-100-point ranking scale.

Finally, how much should you spend on a bottle or wine? The best way that I know how to answer that question is to describe my wine buying strategy which, incidentally, may not be the best way to buy wine.

The short description of that strategy is that I like drinking red wine, but I really hate paying a lot for the privilege. To expand on that, first start with the ratings. Without the ratings you are buying blind. Most wines are unrated. If they are rated, they usually will only have one rating in which case you need to have a good feel for how the rater’s judgement fits in with your tastes in wine. Robert Parker is my personal choice. His ratings closely match my own. If he hasn’t rated a bottle of wine, I give it a pass. In the ten years or so that I have been depending on his ratings he has only let me down twice. Both times I felt his ratings were too high, which brings up a useful caution. When you run across a highly rated wine that is less expensive than normal there is a good chance that the rating should be lower than stated rather than you are getting a great deal on a great wine. The second part of purchasing wine is to recognize that for any given varietal whether a cab, a merlot, or whatever, a similar rating should provide similar tastes and aromas for that varietal regardless of where it came from or who produced it. I get a lot of grief for this statement but I’m sticking with it. If you accept this premise, then it really makes sense to buy the least expensive wine available for any given rating. In 2023 that means you will be drinking wine from Argentina, Chile, and Spain. A few years ago, Portugal produced some great inexpensive wines but that has changed dramatically since 2021. U.S. wines, California wines in particular, are good, exceptionally good even but overpriced. No bang for the buck in Napa.

Using this strategy, I consistently buy 90-91-point, occasionally 92–93-point wines ranging in price from $9-17 per bottle. 94-point and higher rated wines are generally beyond what I’m willing to pay. Cheers.

Wine Pricing References and Readings:

- The Billionaire’s Vinegar. By Bryan Miller. The New York Times. 2008

- A Counterfeit Wine: A Vintage Crime. Uncredited. CBS News. 2013

- Wine quality Ratings Versus Price in the Wine Enthusiast Magazine. By Antonio Carloto. ResearchGate. 2017

- The Six Attributes of Quality in Wine. By Antonio Capurso. Wine and Other Stories. 2019

- Wine Valuation Guide: Everything You Need to Know How Wine is Priced. Uncredited. I Love Wine. 2019

- What is Terroir? A Beginner’s Guide. By Antonio Capurso. Wine and Other Stories. 2020

- Weighing Wine Scores Against Price. By Kathleen Willcox. Wine Searcher. 2022

- List of Wine-Producing Regions. Uncredited. Wikipedia. No date

- Reality of Wine Prices (What You Get For What You Spend). Uncredited. Wine Folly. No date

- Wine Aging Chart for Reds and Whites. Uncredited. Wine Folly. No date