Boris Pasternak (1890–1960), Russian poet and novelist, spent a decade creating his singular opus, Doctor Zhivago, completed in 1956. More than a historical narrative, it is a philosophical cathedral, a novel constructed of haunted Romanticism, moral reckoning, and symbolic renewal. Set against the dissolution of Tsarist Russia and the disillusionment of revolutionary aftermath, the book crosses the bridge from imperial decay into the intoxicating dream of collective transformation, only to watch that dream unravel into a black hole of exile, violence, and starvation.

This arc of collapse recalls the spiritual bargain Thomas Mann dramatizes in Doctor Faustus, but where Mann’s protagonist descends into metaphysical madness, Doctor Zhivago journeys through the quiet but unrelenting erosion of the soul. He does not perish; he endures, but with dimming strength and drive. The rails he rides are not toward damnation but disillusionment. And still, beams of light pierce the fog: rays of love, recollection, and art that suggest the possibility of meaning and rebirth.

As Nikolai Nikolaievich says early in the novel, “the whole of life is symbolic because it is meaningful.” In this way, the prose becomes Pasternak’s metaphorical terrain, thick with fog, fractured history, and spiritual yearning. The appended poetry, by contrast, is a sudden clearing. Here, the truth is not narrated but sung as parables: psalms.

Pasternak stands in conversation with his literary ancestors, not in imitation but in integration. Tolstoy’s presence is unmistakable, the historical sweep as personal crisis, the aching attention to moral choice. But where Tolstoy moves with structural precision, Pasternak drifts with mystical defiance. His narrative resists symmetry. His characters do not seek ideology, they search for grace.

Symbolist in sensibility if not in allegiance, Pasternak paints with metaphysical hues. As Nikolai Nikolaievich reflects, it is not commandments but parables that endure, not doctrine but symbol. Life, for Pasternak, is sacred not by design but because of its trembling unpredictability.

It is no accident that Hamlet opens Zhivago’s verse collection. The parallels run deep: both Hamlet and Zhivago move through time like exiles from history itself, cast adrift in worlds too cruel for their contemplative souls. When Pasternak writes, “I consent to play this part therein,” he evokes both the tragedy and transcendence of bearing witness. Zhivago performs his role, but lives another life, internal, poetic, unreachable: above the fray, but corrupted by the psychosis below.

His poems chart this existential divide: March, an ode to ugliness and beauty; Holy Week, a quiet redemption; Parting, remembrance caught in an unfinished gesture. In Garden of Gethsemane, Pasternak, born Jewish, philosophically Christian, offers the novel’s spiritual heartbeat and epitaph: “To live is to sin, / But light will pierce the Darkness.”

Perhaps nowhere is Pasternak more intentional, and more misunderstood, than in his use of coincidence. Critics have dismissed the improbabilities: chance meetings, reappearances, entwined fates that strain believability. Yet, viewed symbolically, they form a system. These moments are not narrative indulgences; they are metaphysical punctuation marks, appearing when a character risks dissolution and irrelevance, summoning memory, recognition, or spiritual breath.

These recurring events hint at resurrection, not just personal but societal. Pasternak suggests life moves not in straight lines but in spirals and cycles. Coincidence becomes a kind of syntax for recurrence, for unfinished conversations rekindled in new voices. Meaning doesn’t unfold; it echoes amplified.

Again and again, children appear, observers, inheritors, blank slates. In them lies the novel’s quiet eschatology: renewal not through revolution, but through the uncorrupted eye. These youths do not argue ideology. They carry memory unwittingly. They are the future poets whose truths will be elemental and free, like wind through the trees.

If Doctor Zhivago is a Passion, then its resurrection comes not in fire, but in continuity. Not in triumph, but in scattered verses, remembered, revived. Pasternak’s salvation is lived: grace through endurance, beauty through suffering, renewal through remembrance.

Banned in the Soviet Union upon completion, Doctor Zhivago was smuggled to Italy and published in 1957, igniting an international phenomenon. The CIA distributed the book behind the Iron Curtain as a weapon of quiet revolt. Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1958, then compelled to decline it under state pressure. And still, by 2003, the novel had found its way into Russian classrooms.

This was not just a novel. It was a voice buried and reborn.

Pasternak’s opus is not a chronicle of a man or an era, but a symbolic landscape of what it means to remain human in the machinery of history. A tale not of revolution’s glory, but of the soul’s refusal to be mechanized. It rejects dogma in favor of parable, certainty in favor of consequence, ideology in favor of grace.

Doctor Zhivago teaches us that life may be coincidence, but not accident. That beauty may falter, but goodness moves quietly. And that sometimes, when all else falls away, it is poetry that remains, whispering its eternal truths into the trembling heart of history.

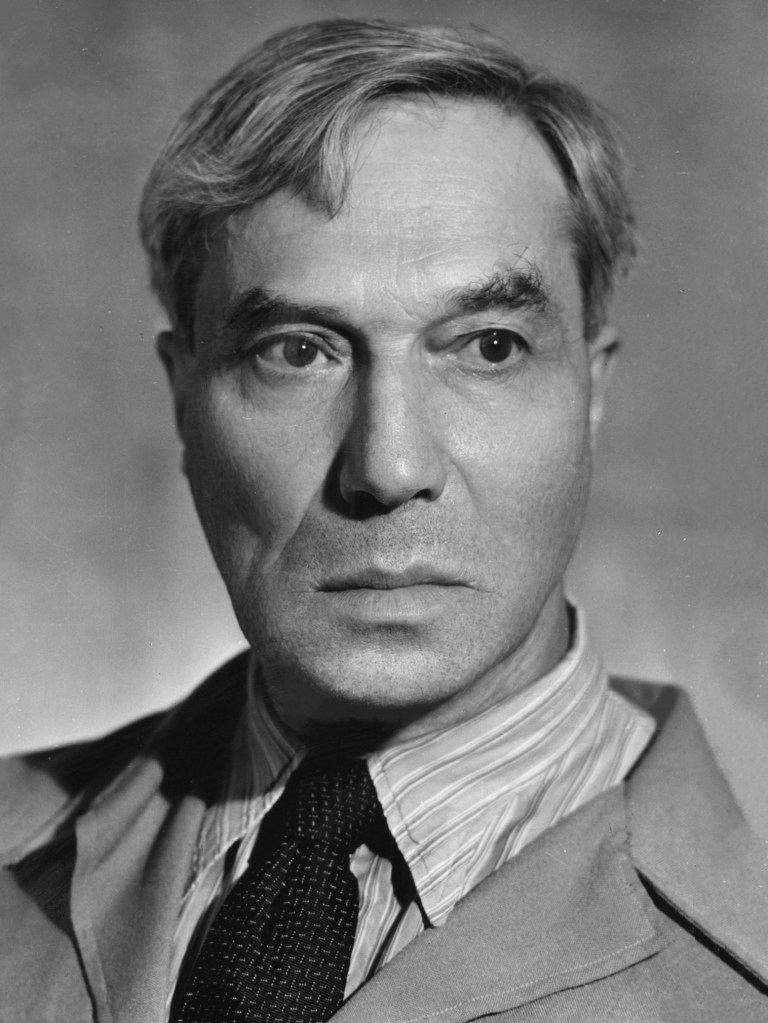

Source: Dr. Zhivago by Boris Pasternak, 1957. Graphic: Boris Pasternak, 1959. Public Domain.