On 12 March 1664, King Charles II, eager to expand the English empire and reward his loyal brother James, Duke of York, granted him a vast swath of North American territory. This prize included New Netherland—stretching roughly from the Delaware River to the Connecticut River—plus scraps of modern Maine and islands like Long Island, Martha’s Vineyard, and Nantucket along the Atlantic coast. Whether Charles saw the Dutch, who currently claimed and occupied most of this land, as a mere obstacle to be swept aside or a challenge for a later Machiavellian showdown isn’t entirely clear in today’s histories. But that’s a story for a later post. What’s certain is that on September 8, 1664, some 300 British troops under Colonel Richard Nicolls peacefully seized New Netherland, renaming its heart, New Amsterdam, as New York.

The conquest raised a question: what to do with the Dutch, French, Walloons, and other non-English settlers now under British rule? The Articles of Capitulation, signed that day, were generous: these residents could keep their property, trade rights, and personal liberties. They weren’t forced out or stripped of their livelihoods—a pragmatic move to avoid rebellion in a colony where the Dutch outnumbered their new overlords. But this deal had limits. Without British citizenship, they owed no loyalty to the Crown, couldn’t pass property seamlessly under English law, and lacked full access to British markets. Enter the curiously dated Naturalization Act of 12 March 1664—more on that head-scratching date in a moment.

This act offered foreign-born settlers a path to English subjecthood. By swearing allegiance to the Crown and paying a fee—described by some as modest, by others as steep—they could gain the rights and privileges of English subjects. The exact fee is lost to time, but it was likely hefty enough to filter out the poor while drawing in merchants and landowners eager for legal and economic benefits. The act aimed to stabilize the colony’s economy, secure political control, encourage growth, and align local realities with British common law.

In mid-17th-century England, citizenship hinged on jus sanguinis—citizenship by blood. Only children of British parents were natural subjects; foreign-born adults, like New York’s Dutch settlers, needed a legal workaround to join the fold and fully participate in colonial life. The act filled that gap, promising a unified British colony over time.

History pegs this Naturalization Act to 12 March 1664—the same day Charles granted James the land—yet the English didn’t hold New Netherland until September. A citizenship act before possession seems nonsensical. One plausible explanation? It’s a backdated fiction. The real policy likely emerged post-conquest, perhaps in late 1664 or 1665, as Nicolls integrated the Dutch population. Linking it to March 12 could’ve been a deliberate move to dress up the original grant as lawful and inevitable—a tidy origin story for English New York. The Articles handled the surrender’s chaos; naturalization was the long-term glue, and pinning it to the charter’s date cast the shift from Dutch to British rule as seamless and legitimate.

Addendum: The Evolution of British Citizenship

British subjecthood didn’t stay rooted in jus sanguinis. Between 1664 and the mid-18th century, it gradually shifted toward jus soli—citizenship by soil. By the time Sir William Blackstone penned his Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765–1769), anyone born in the Crown’s dominions was a natural-born subject, regardless of parentage. This held until the British Nationality Act of 1981, which dialed back unconditional jus soli. Now, a child born in the UK needs at least one parent to be a British citizen or a settled legal resident to claim citizenship—leaving others out of the fold.

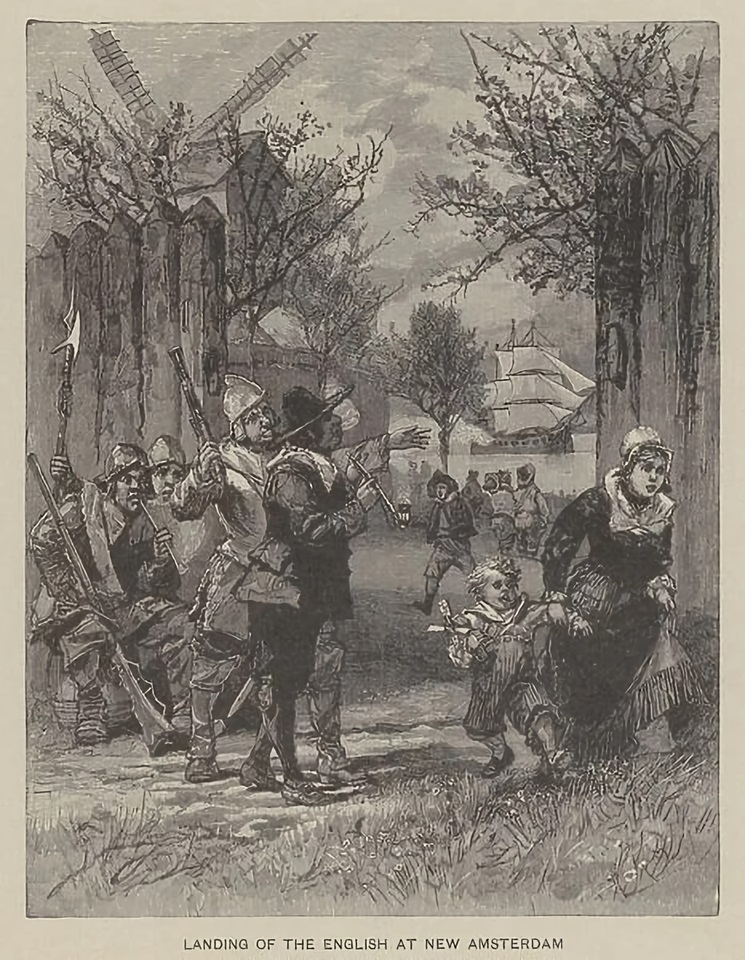

Sources: America’s Best History; discussions with Grok 3. Graphic: Landing of the English at New Amsterdam, 1664, produced 1899, public domain.