Francisco de Goya, court painter to the late 18th century Spanish royalty, was no great admirer nor groveling sycophant of his patrons. He portrayed them, literally and figuratively as pretentious hypocrites and regal bores. Somehow, he was able to convince the king and queen that his paintings embodied their imagined over-hyped majesty. They did, just not in the way the royal couple envisioned. Goya sold the fiction ‘the king has no clothes but isn’t he marvelous’ with the aptness of Hans Christian Andersen, and it likely paid handsomely.

Modern portraitists of the rich and famous seem to follow a similar creed. A veiled contempt that comes through in their brushwork. Faces frozen in contempt for the world beyond the palace, bodies wrapped in pop-art symbolism, palates of unmistakable gauche screeching, all undermining an uplifting narrative of benevolent power and grace. And, like Goya, they persuade their patrons that all is light and beauty, even though the cracks and shadows are front and center.

A portrait is not just posture, paint, and brushwork; it is an appointment with truth. Maybe just one minor truth, but truth none-the-less. The true artist illuminates the soul where he finds it. An artist’s symbolic performance can flourish in irrelevance of style, but the truth must come out.

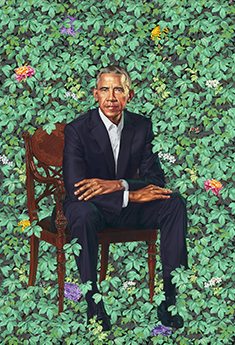

Kehinde Wiley’s 2018 portrait of Barack Obama is a curious specimen. It goes beyond tradition into overt symbolism that lands in a duality of truth. It’s a disruptive panel bordering on cartoonish messaging. Botanical motifs of chrysanthemums and lilies in the background, engulfing Obama seated on a wooden chair with six fingers. A portrait not of a President but a topiary clipped into a pose of nonchalance and a distant soul focused on…nothing. The overall effect is one of mockery. Is Wiley mocking the President or is the President mocking his audience, maybe both. Wiley sold it as an informal symbol of a great man but maybe he was painting what he saw. A man whose legacy, much like the foliage behind him, now blooming with grandeur but fading to irreverence over time.

Compare this to Jonathan Yeo’s two portraits of King Charles III and Camilla. The former awash in crimson ambiguity, with vague lines of demarcation. Its symbolism is gaudy and obtuse: the lone butterfly, the seeping reds, the gaze misplaced: together, a haunting emergence from a bloody mess. A reliance on cryptic visual metaphors over soulful revelation. A painting wishing to express depth, and it does, but as a downward drift into circles of Dante rather than a royal crimson of empire. Yeo does not explain much of his trajectory of the portrait. He seems satisfied to leave the interpretation to others. Camilla says it captures him perfectly. But what it captures is not a dignified, confident king, but one who bartered his soul for the crown which Yeo captured impeccably, consciously or not.

Yeo’s 2014 portrait of Camilla, HRH The Duchess of Cornwall, compliments his painting of King Charles: another study of a lost soul. A picture of non-essence. A painting of emotional neglect. Blotches of earth tones for blood and straight lines of iron and fog for character and birthright. In the background vertical lines of changing width suggestive of a perspective view of Camilla sitting in the corner of a prison cell, trapped in a unwanted life, with sub-horizontal lines crossing her clothing like lines of filtered light originating from a broken, tilted structure of casements in disrepair. Windows into a soul without balance or integrity. A blotchy face, pressed lips and the piercing eyes of disgust are the caricature of woman who finds the world a bore and the artist gives wholehearted ascent to her wishes.

Yeo’s portraits of the royal dyad are of tragic symmetry. Charles as an entitled blood-soaked monarch, lost in a mythic realm of post over duty. Camilla is a shadow brought along for form without script, shadow without light.

Each of the three portraits in the triptych, at first blush, are merely lacking in technique or likeness and immensely soulless. With further exposure and examination, the artists have captured their subject’s essence. They are gauche and grotesque, but the painter’s truth is bleeding through. They portray their subjects as an antithesis to their public persona. Wiley’s Obama is lost in symbolic foliage, Yeo’s Charles stands embalmed in a crimson history of unrestrained desire, and Camilla appears accidentally sentenced to royalty by an artist barely able to contain his disdain.

Symbolism, when wielded well, lives in the background, like Botticelli’s Primavera, where flora guides the viewer through renewal without eclipsing the figures themselves. Art that elevates does so through integration, not ornamentation. Symbolism must serve beauty, and beauty must point toward goodness. But if the truth isn’t of beauty, what then?

True portraiture captures the soul and, if need be, is not afraid to offend. It does not flatter blindly, nor does it subtract without cause. It seeks something elemental. It lets the canvas speak, the brush guide, and the palate reverberate with reality. Great portraits are a reckoning of the soul, not decoration of form.

Graphics: President Obama by Kehinde Wiley, 2018. King Charles and Camilla by Jonathan Yeo, 2023 and 2014. All copyrighted. Used for purposes of critique.