The 14th Amendment, introduced during the Reconstruction era, was crafted to address legal and constitutional deficiencies exposed after the U.S. Civil War. Its first sentence; “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside“, has become a focal point for competing interpretations. Much like the Second Amendment, its wording has sparked legal and grammatical debates, particularly surrounding the clause “and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”

The Second Amendment faced similar scrutiny for over 200 years, particularly its prefatory clause, “A well-regulated Militia.” This ambiguity was finally addressed in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), where the Supreme Court clarified that the historical record and documents like the Federalist Papers supported the right of private citizens to own firearms. The Court also ruled that the prefatory clause did not limit or expand the operative clause, “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.“

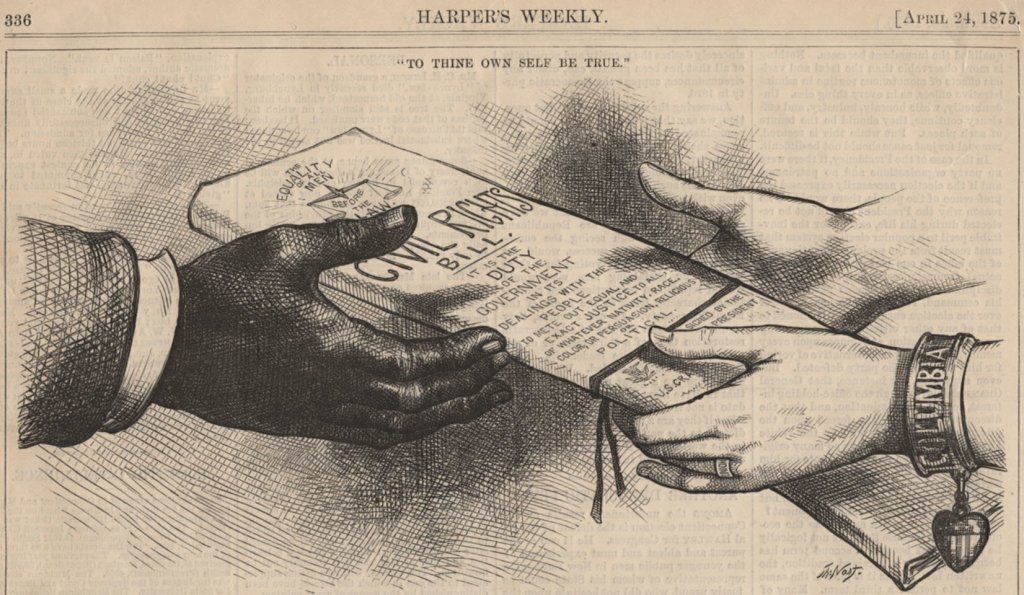

Likewise, the 14th Amendment’s clause “and subject to the jurisdiction thereof” remains unsettled, awaiting similar historical and grammatical scrutiny to solidify its interpretation. Initially aimed at protecting freed slaves and securing their citizenship, this provision has since invited broader interpretations in response to modern challenges like immigration.

The framers’ intent during Reconstruction was to ensure equality and citizenship for freed slaves and their descendants, shielding them from exclusionary laws. At the time, the inclusive principle of jus soli (birthright citizenship) aligned with the nation’s need to address the injustices of slavery and foster unity among the country’s existing population. However, changing migration patterns and modern cultural dynamics have shifted the debate. The ambiguity of “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” now raises questions about its application, such as how jurisdiction applies to illegal immigrants or children of foreign diplomats, in a globalized world.

Legal precedents such as United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898) affirmed that nearly all individuals born on U.S. soil are citizens, regardless of whether their parents’ immigration status is legal or illegal. While this aligns with the practical interpretation of jurisdiction, it has spurred debates about the fairness and implications of modern birthright citizenship practices.

Immigration today involves a broader spectrum of cultures and traditions than during earlier waves, when newcomers often shared cultural similarities with the existing population. Assimilation, once relatively seamless, now faces greater challenges. Nations like Britain and Germany have recently revised their jus soli policies to prioritize the preservation of societal norms. The unresolved question of how to address declining populations further complicates the debate; a debate with the citizens that has not occurred much less resolved.

While originally crafted to address the systemic exclusion of freed slaves, the 14th Amendment’s principle of birthright citizenship continues to evolve in its application.

Graphic: 14th Amendment Harper’s Weekly.