“Have no fear of perfection; you’ll never reach it.” – Dali.

Salvador Dalí was the entertaining, surrealist voice of the masses. His dreamlike spectacle of melting clocks and flamboyant persona captivated popular culture, injecting eccentric brushstrokes into the lives of the disengaged and disinterested. Dalí spoke directly to the public’s fascination with dreams and absurdity, transforming art into a theatrical experience and a giggly poke at the eminent egos on high altars.

Dalí was a 20th-century Spanish artist who drew from influences such as Renaissance art, Impressionism, and Cubism, but by his mid-twenties, he had fully embraced Surrealism. He spent most of his life in Spain, with notable excursions to Paris during the 1920s and 1930s and to the United States during the World War II years. In 1934, he married the love of his life, Gala. Without her, Dalí might never have achieved his fame. She was not just his muse but also his agent and model. A true partner in both his art and life. Together, they rode a rollercoaster of passion and creativity, thrills and dales, until her death in 1982.

Dalí had strong opinions on art, famously critiquing abstract art as “inconsequential.” He once said, “We are all hungry and thirsty for concrete images. Abstract art will have been good for one thing: to restore its exact virginity to figurative art.” He painted images that were real and with context that bordered on the not real, the surreal. For those who believed that modern abstract art had no life, no beauty, no appeal, he provided a bridge back to a coherent emotional foundation with a dreamlike veneer. Incorporating spirituality and innovative perspectives into his dreams and visions of life.

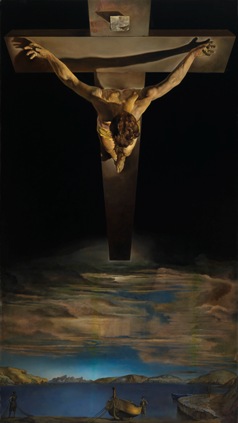

The Persistence of Memory (1931) is Dalí’s most recognizable and famous painting, but his 1951 work Christ of Saint John of the Cross is arguably his most autobiographical and accessible piece. A painting dripping with meaning and perspective, Dalí claimed it came to him in a dream inspired by Saint John of the Cross’s 16th-century sketch of Christ’s crucifixion. The perspective is indirectly informed by Saint John’s vision, while the boat and figures at the bottom reflect influences from La Nain and Velázquez. The triangular shape created by Christ’s body and the cross represents the Holy Trinity, while Christ’s head, a circular nucleus, signifies unity and eternity: “the universe, the Christ!” Dalí ties himself personally to the crucifixion by placing Port Lligat, his home, in the background. He considered this painting a singular and unique piece of existence, one he likely could never reproduce because the part of him that went into the painting was gone forever.That part is shared with his viewers, offering a glimpse into Christ’s pain, Dalí’s anguish, and his compassion: an emotional complexity that transcends mortal comprehension.

Source: Salvador Dali by Robert Descharnes, 1984. Graphic: Christ of Saint John of the Cross, Dali, 1951. Low Res. Copyright Glasgow Corporation.